People

The Voice Of A Free Man:

Ryszard Kapuściński

by AMANDEEP SINGH SANDHU

The history of Poland and its people is, in many ways, similar to that of the Sikhs. Here, a noted Sikh-Indian novelist explores the life-work of a man who not only exemplifies Polish sensibilities but is considered a giant in the field of journalism worldwide. Though also a noted poet and photographer, it was his courageous and insightful reporting from around the world, especially Africa, that earned his writings the label of "magic journalism".

It was Mr. Zbigniew Igielski at the Polish Visa Office who asked me why I wanted to go to Poland for a holiday. I mentioned how, at my own book launch a few years ago, a journalist had asked me who my favourite writer was and I had instinctively mentioned Ryszard Kapuściński.

Almost no one in the audience knew him, neither did the interviewer, but about 15 years ago, Kapuściński had opened my eyes to the world and ever since I have wanted to walk the streets he walked on in Warsaw and, if possible, in the world.

Towards the beginning of his career, in 1955, Ryszard Kapuściński wrote a piece commissioned by the Communist party for Sztandar Młodych on Nowa Huta, the Orwellian industrial town created by the Soviet regime outside Kracow. He was critical of it. Yet, owing to differences within the party, not only did the authorities let it pass, they even awarded him the Golden Cross of Merit.

After which he joined Polityka, a periodical of the Communist Party. His beat was interior Poland. In 1962 he published a book on his travels: The Bush. He then worked for the Polish Press Agency, the PAP, as its only foreign correspondent during the years of the Cold War.

Through the 1960 and 70s, he witnessed twenty-seven revolutions and coups, mostly in Africa, and was jailed 40 times and survived four death sentences. His books include:

- The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat (1978, on Haile Selassie's regime in Ethiopia)

- Shah of Shahs (1982, on Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran)

- Imperium (1994, travels to the disintegrating Soviet Union, both a personal travelogue and a memoir)

- The Shadow of the Sun (2001, essays spanning four decades, forming a unique portrait of Africa)

- Travels with Herodotus (2007 on his engagement with the history of Europe through the Greek classic and with Asia - India/China through his own travels)

He called his work ‘Literary Reportage’ and the critics hailed his style as ‘Magic Journalism’. He remains the second most translated Polish journalist/ writer of all time.

The Emperor was named Book of the Year by The Sunday Times of London.

In 1999 he won the biennial Hanseatic Goethe Prize awarded by the Hamburg-based foundation, the Alfred Toepfer Stiftung; in 2005 the Italian Elsa Morante Prize (Premio Elsa Morante, Sezione Culture D’Europa), for his Travels with Herodotus.

In 2001 the literary Prix Tropiques of the French Development Agency for his book, The Shadow of the Sun, which had a year earlier been named the best book of the year by the French literary monthly, Lire; the book also won the Italian literary award, Feudo Di Maida Prize for the year 2000.

In 2000, the prestigious Premio Inter-na-zio-na-le Viareggio-Versilia.

In 2003, the Premio Grinzane Cavour per la Lettura in Turin, and so on.

Since his style was unique, often special prizes or categories were created and awarded to Kapuściński. In their obituaries, Der Spiegel and the BBC hailed him as ‘the best reporter in the world’.

After his death in 2007, there has been a renewed interest in his work, including a biography which hints that perhaps he had to exchange information to keep the Soviet powers happy and that he exaggerated the facts he depicted through his writings on Africa.

When Mr. Igielski asked me what interested me in Kapuściński I stated: Kapuściński had certainly travelled the world but India was the first country he visited. In India we know that good story telling comes from the interstices of facts and fables. He might be accused today but I derive inspiration from him.

He wrote about us, the ‘other’. But he too was an ‘other', his nation behind the Iron Curtain -- an oppressed society, othered by the Western world and by the Soviet regime.

We were both powerless yet he helped me, and all his readers, understand how political power operates in the larger world. The Cold War is now over and we perhaps are no longer sharply divided into an 'us' and 'them' as in his times, but there still a lot to learn from his deep humanism.

* * * * *

Lidia Puka had arranged the meeting with Kapuściński’s widow, Alicja Kapuścińska, at 3 in the afternoon on a bright sunny day in the end of May 2011.

Lidia’s mother, Mrs. Beata Puka, had once sent a draft of her book to Ryszard Kapuściński and he had returned it with a foreword. She told me that when he taught at the university he would say, 'A journalist has to first be a good human being.'

Lidia arrived at Alicja and Ryszard Kapuściński’s gate carrying a beautiful big bunch of white and orange gladiolas. I smiled. I had not thought of flowers. She told me she had come because she wanted to meet Mrs. Kapuścińska but also because she felt that though the latter knew English, she might feel more comfortable in Polish.

It wasn't 3 pm yet so we waited outside the gate when a voice called out from the first floor balcony. Alicja asked us to come in. Lidia asked me to present the flowers and I also gifted her a small copper wall hanging from Bastar, Central India, with figures of men and women engaged in daily work - ploughing, wood gathering.

Alicja has lovely sunny eyes and a warm disposition. She told us how a distant relative of hers has married someone from India who teaches at a high school in Warsaw. So, India is now a part of her family. She also showed us pictures of one of her great-grand children, who is part Japanese. The small-talk made us feel at home and we settled on the simple, beige cloth covered sofa in the drawing room.

She took the chair at the head of the table. ‘It is my habit,’ she said.

Q You might be getting many visitors, don’t you get tired?

A I quite enjoy it actually. I try not to take more than one visitor or a group a day but I like it that readers come and connect with their writer. I see it as my job to preserve his legacy: both his work-place which was our home, and the hundreds of agreements with publishers, translation rights, rights to reuse pieces, and now have a prize in journalism instituted in his name. I find it my job to preserve the writer’s legacy, I do all I can to keep him as fresh as he comes across to his wide variety of readers.

(The Kapuściński award for literary reportage was instituted on the journalist’s third death anniversary in 2010 by the City of Warsaw and the newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza.)

Q You are a doctor (a paediatrician) ...

A Yes, I worked at the hospital for 35 years and have now been retired for over a decade. But I remain much more busy than I was at the hospital. In the Communist years, hospitals were hard places to be in, especially with children where there was a scarcity of food. I like this work, keeps me engaged. It is the idea that I am preserving his legacy. Then I have my grand-children and now great grand-children.

Q Did you ever accompany Kapuściński on his duties?

A The authorities let me go to take care of him at times when he fell very ill. A few times in Africa. Then when he was posted in Mexico as a News Attaché he took me along. I worked in the hospitals there and was appalled to see the size of the babies:

so small, so malnourished. I worked there for three years feeding them, nursing them.

Q Kapuściński saw so much violence, millions dead. How many revolutions?

A 27 (and she laughs). We change with just one or two … He did see a lot. Four times he got the death sentence. Many times he was caught in fights and was threatened with knives and bombs and guns. We never kept count of how many times he was arrested or detained by police and military. His work was risky but he wanted to do it.

Q Did witnessing all the horror, all the deaths, depress him?

A No. He believed he had a task at hand and he went about doing it. He believed in his work and he fulfilled it.

Q Even Mother Teresa is reported to have doubts. She wrote notes in her diary to God. How did Kapuściński escape the feeling?

A In every situation he documented, he knew both sides: those who killed and those who were being killed. He chose to tell the story of those who were being killed.

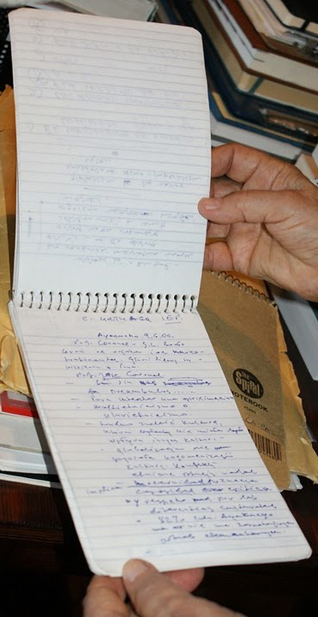

Q How often did he revise his stories?

A All the time. He would write long hand. He would look at his long hand piece and be dissatisfied. He would cut, change, make the whole piece so shabby. Then he would move to the typewriter. Then again cut and change. He never stopped. But

he never took to the computer. He felt it destroyed rigour. The good thing was he had an agreement with a newspaper that he would write columns for them. He had deadlines. Else, he would have never completed writing anything.

Q What, according to him, was the most important aspect of his writing?

A The first line. He would say: If I get the first line right, I can get the whole book out. Once he was very disturbed. He was upset, in a mood for a few weeks because he could not get the first line. Then one day, he came down for lunch. We were casually sitting and he said: I got it. The first line.

And I said: What? Really? I was so relieved. He smiled and he told me the first line: "The Emperor had a little white dog, named Lulu ...'

We went up, to his study, and he read to me the first few pages. It was such a beautiful moment. (Her face shines as she tells the story).

Q Who did he read to?

A To me. Always to me. He read to me everything he wrote.

Q Did you comment on his writing?

A Sometimes. (She feels shy.) Very rarely I would suggest something. He would consider it. It would be incorporated in the next draft.

Q Where did he write?

A In this house, upstairs. In his study. He was always there, working. Working all the time.

Q Did he write in a routine?

A He just worked and worked. Reading, writing. He used to tell his students: to write one book you must read at least a hundred. He asked me to remove his telephone. I had to answer all his calls: Mr. K is busy. Mr. K will call back. Mr. K will

respond.

Lidia's Q How did you meet, the both of you?

A He and I were students of history at the Warsaw University. It was after the Second World War, we were under Communism. Friends used to say that at dances we both would dance only with each other and not look and talk with anyone else. Guess that was our love. He encouraged me to study medicine, to become a doctor. (She sits up, pauses, and then continues.)

Within a year of meeting we were married. Within a year of marriage I was pregnant. He was still living with his family and I lived in the ladies hostel. His mother was ill. Luckily, she recovered and he got a job as a reporter. Then he was allotted a small apartment and we moved in.

Lidia's Q And then?

A Slowly he started travelling and I was extremely busy with my work at the hospital. Even when he came back from travels there would be one or two nights a week when I would be on 24-hour shifts. But it all worked out. He would tend the home when I was away. We shared a deep friendship and from it, love.

You know he was born March 4, 1932 and I on March 4, 1933.

Q What, if you now look back and wonder, would you say made the marriage work?

A I never told him to not to do something he wanted to do ... that's all. I never stopped him or questioned him about what he wanted to do. I guess we had that trust.

Q Did Ryszard believe in an idea of Justice? Or, did he consider it his task to bring to the world the stories of the dispossessed people?

(Lidia tries to translate but Alicja raises her hand and looks at me point-blank, and says ...)

A The latter. He believed there are many who wish to be heard but are not heard. He wanted to bring to the world the messages of those who are not heard. That was how he defined his role to himself.

Have you read all his books?

I (Amandeep) answer: 5 or so. I am carrying one with me right now.

(I pull out my copy of Travels with Herodotus. She takes it from my hands.)

Alicja: Is he read in India?

Amandeep: Well, I learnt of him in a journalism class. I can’t say how many read him these days, you know, with TV and websites, but he remains very relevant.

(She looks at the name of the publisher and says ...)

Okay, Penguin, they have rights.

* * * * *

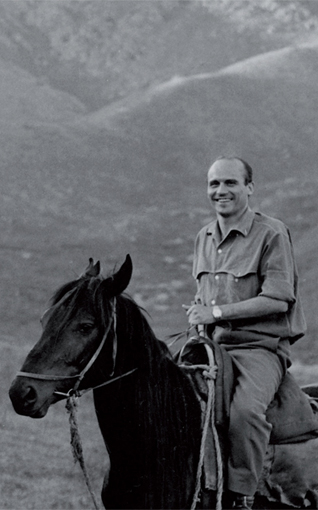

We go up to see the study. At the door are grass shoe covers, the kind used by people in Plinsk, where Kapuściński was born, to cover their shoes from the always slushy ground. Some pictures from Africa that he took. The study is an L-shaped room, about as big as a badminton court. It is lined with books. There are thousands of them, so it looks small.

Alicja has preserved it just the way it was on the day he passed away. His typewriter stands on his work table along with a picture of his hand signing a book. On the side of his table are pen stands with hundreds of green, blue, red pens. On the walls hang artefacts from around Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Alicja says: He loved pens. At his funeral many people brought pens to leave at his side.

Q When did he start working from this study?

A We bought this house around 22 years before. Before that we lived in apartments. When we bought the house Ryszard was thinking of writing about Idi Amin, Uganda. But then Glasnost and Perestroika happened and the mighty Union of Soviet Socialist Republic crumbled. So he went to Russia for 13 months to report on the break up of the Soviet empire. I took permission from the municipal authorities to renovate the upstairs of the house and created this study. He came back and loved it. Since then, for next last 20 years he lived here and worked here most of the time.

Q How did he deal with fame?

A When The Emperor was translated and the world press came looking for him, he was taken aback. But he remained modest. Once at a book function, the organisers closed the doors on some readers because they had an official dinner scheduled for him. He got angry and asked the organisers to open the doors. He said, these people have travelled hundreds of miles to come and be here and you want to prevent them? This love for people kept him going. When he met people he would ask them what they did, who was in their family, the names of their children, what work they did, simple small questions. In fact, journalists had it the toughest with him when they came to interview him. They would joke: With him we do not know who is interviewing whom. His ability to listen is a legend.

(She smiles.Then she shows us a poem by Kapuściński's Vietnamese translator. Lidia translates it into English as she reads the Polish.)

Through all your work,

and schedule,

you make time to listen

to me.

Be interested in me.

Even when I wanted

to stop,

you made me reveal,

my dark secrets.

Today the light

in your study glows,

for you are not gone,

and are around,

and will return soon.

Then Alicja tells us how, a few days after Kapuściński's passing away, their neighbour called her one night and said that he felt odd that the light in Kapuściński's study is off.

"It was never off while he was alive, please put it on," he requested.

That moment I too requested her to keep the light on that evening.

We talk briefly about the gift I have brought for her.

She explains that Kapuściński did not only start his journeys with India, he even ended his touring with India. His last visit was about a year before he passed away but he could not travel for too long. He went from Delhi to Dharamsala and fell ill so had to come back.

"In fact," she said, "I can’t recollect if he went anywhere after that trip. So his world exposure started and ended with India."

"And the books," I said.

She gave a wide smile.

Q How many passports did he finally have?

A Just one. Issued after the Solidarity Movement (1989). Earlier whenever he had to travel he would request the authorities and they would call him for an interview. It would be a long interview, 3 hours, 4 hours. Then they would issue him a new passport. When he came back, they took the passport back and interviewed him again. He did not know his interviews were being recorded. That is why the biographer found a huge file on him (she holds her hands apart about 18 inches) in the state archives and accused him of being a supporter of the Soviet regime. It was just a job. He had to face the interviews.

In fact, when the revolution broke out in Zanzibar, he was the first journalist in the world to report it. Even at Angola he was the only journalist for almost three months.

But the Soviets did not believe him. So, he had to ask the TASS (Soviet News Agency) reporter to send the story. Typically, a case of the Soviets believing what they heard from their own sources.

Q Did he ever have to work in an office? Or was he always on the field, reporting?

A No, he was either reporting or he was at home. After the Zanzibar incident the Soviet authorities asked him to take over as editor, do an office job. He refused. He wanted to report and he kept doing that or writing columns.

Q So, can we say, that in the Soviet regime, behind the Iron Curtain, he was the only free citizen who could live the way he wanted to live?

A (She laughs.) That is true. In spite of the regime, he was a free man.

Assisted by Lidia Puka who works in Energy Conservation in Warsaw, Poland.

Amandeep Singh Sandhu is the author of a novel, "Sepia Leaves". His next novel, "Roll of Honour", is due to be released shortly. He works in Information Technology in New Delhi, India.

April 21, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Joanne Nezi (Greece), April 21, 2012, 1:08 PM.

Thank you for this article! I too am a great fan of Ryszard Kapuscinski's. Being a very careful listener and focusing entirely on the other person is what makes a great journalist, and a great writer. I have, I admit, wondered a bit about the ethics of his book on Haile Selassie, even though my inclination was to believe that though it's not literally true, it's psychologically and sociologically true. Mr Amandeep Singh has provided me here with a very good answer: there is no story, no narrative, that is not at least partly fictional.

2: Nandini (Chennai, India), April 21, 2012, 2:55 PM.

What a beautiful interview! I feel like I was in the room, listening to this, watching this happen. I haven't read Kapuscinski yet (though I have read about him), but want to now.

3: Sunny Grewal (Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada), April 21, 2012, 3:18 PM.

It's an interesting notion to compare the fates of Poland and Sikh Punjab. Poland was defeated and divided up between the Russians and Germans. The Sikhs were defeated by the British and then a hundred years later the Punjab was divided between Pakistan and India.

4: Srikanth (Roanoke, Virginia, U.S.A.), April 21, 2012, 8:06 PM.

Thanks for your interview that sheds light on a fascinating (and controversial) literary figure, Aman. Kapuscinski's style reminds us that the dividing line between literature and journalism is not always clear, and this links up in interesting ways with critiques about the politics and accuracy of some of his writing.

5: Shubho (Delhi, India), April 21, 2012, 11:54 PM.

Thanks for sharing this experience. Am a big fan. What is the parallel between Polish and Sikh history?

6: Avi Das (Kolkata, West Bengal, India), April 22, 2012, 2:27 AM.

Insightful interview. Most interesting is the fact that he witnessed twenty-seven revolutions and coups. I wonder if he had a global view on revolutions and coups and their causes? Thank you for introducing a mind worth further exploring.

7: Samuel Thomas (Darjeeling, India), April 22, 2012, 2:47 AM.

Thank you for sharing this article and interview, and your personal introduction to the world of Ryszard Kapuscinski. I must admit I have not read him - but now I will definitely. I liked everything about this but most of all the way it ends - "In spite of the regime he was a free man."

8: A. Joseph (Bangalore, India), April 22, 2012, 4:36 AM.

This is a very interesting interview which reminds me that I must get around to reading "The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat." I've avoided it so far, partly because I spent a good chunk of my childhood in Ethiopia, during Haile Selassie's reign, and haven't been keen to interfere with my wonderful memories of a beautiful and fascinating country.

9: Kirat Kaur (New Delhi, India), April 22, 2012, 5:24 AM.

The parallels between Poland's history and that of the Sikhs are eerie. Both are infused with intense patriotism, nationalism and pride. Both have been overly trusting but have been repeatedly betrayed by other, lesser peoples who have benefited from their (Polish/Sikh) largesse but turned to treachery when it became expedient. Both have bounced back, over and over again, against the heaviest of odds. Both are fiercely independent and impossible to keep down. Both are inherently democratic and egalitarian in nature ... so on and so forth. As a result, the Polish character too is similar to that of the Sikh: loyal, proud, passionate, heavily spiritual, unwavering faith in God, living in the present, big-hearted, trusting, high-in-integrity ... Read their histories and you'll quickly see a similar pattern emerge from the two streams.

10: Lindsay (India), April 22, 2012, 8:08 AM.

Fabulous, Aman. Am so glad you managed to meet her and talk about him. He wasn't obsessed with his own life at all, so this is a treat.

11: Rosalia (Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.), April 22, 2012, 2:44 PM.

What a fabulous and inspiring interview; certainly, Kapuscinski's life could serve as an inspiration for today's journalists, regardless of where they live. Thank you for sharing the fruits of your intellectual curiosity!

12: Maitreyee Chowdhury (Bangalore, India), April 23, 2012, 3:46 AM.

Thanks for introducing me to Kapuscinski. Interesting write up. Curious, was he more of a journalistic influence on you or as a writer? What are the parallels with Sikh history?

13: Amandeep Singh Sandhu (India), April 23, 2012, 9:24 AM.

Thank you, friends. It means a lot to me that you liked the interview and felt you were there witnessing it. To the question of parallels between Sikhs and Poland. I agree with Kirat Kaur's wonderful response. When I traveled in Poland I was struck by how the Poles are a proud people. Theirs is a pride of knowing that they have been wronged against but have not wronged anyone. Their history bears testimony to that fact: though Poland is an older country and the Sikhs too as a community are a much older people, but Poland formally became a nation (Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth) in 1569, around the time of Guru Nanak. For over a century from 1648 to 1764, Poland faced reverses and Polish people lost their nation for another 123 years in 1795. For a century or so after the 10th Guru, Gobind Singh, and until Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Sikhs too fumbled to find a leader who could unite them. The last century has been especially trying with Hitler's invasion of Warsaw sparking the Second World War and the Polish people's truly glorious resistance in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 in which they defeated the Nazis. Similarly, the Sikhs formed a large part of the British Army in World War II and won numerous campaigns. A large number of Poles lost their lives under Nazi occupation similar to Sikh and Punjabi lives lost during the Partition of Punjab. Poland was first betrayed and then taken over by the Soviets. They liberated themselves in 1989 and have come to occupy a much smaller geographical space today. This part is akin to the Sikh struggle for a homeland, Operation Bluestar, the 1984 riots, the emigration, and the shrinkage of traditionally what was Punjab a few centuries ago. Yet, pride and innocence remain the hallmarks of the two communities. Listen to traditional Polish music and listen to traditional Punjabi music, you will hear the folk-root similarities. The hardy worker cuisine, the dresses for rural work lives, there is a lot to chew on ...

14: Edith Parzefall (Nuremberg, Germany), April 27, 2012, 8:30 AM.

Fantastic article and interview. I want to grab my backpack and go traveling. Wanderlust is calling ...

15: Zbigniew Igielski (Warsaw, Poland), January 01, 2013, 9:07 AM.

Dear Mr. Amandeep Singh Sandhu! I am very happy to read about the results of your travel to Poland! The interview is indeed very interesting and shows the spirit of Kapuscinski's books. When it comes to historical facts I feel obliged to correct you: Poles became a nation much earlier than 16th century - it was in 966 when the first ruler of Poland - Mieszko I - caused that Poland was baptized and turned Poles into Christians. The way you compared Sikhs and Poles is very interesting. Congratulations!