Music

Making Time My Own

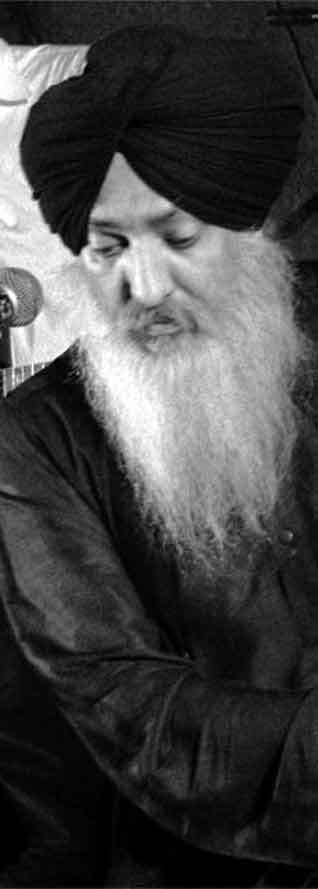

MADAN GOPAL SINGH

I connect with people based on the way they approach the idea of time. Although I think about it in an abstract way, when I sing, I look at time as how it happens during a performance.

Growing up in Punjab, I was exposed to singing traditions that were beat-oriented. You lived in the music from moment to moment, but you did not have an idea or picture of the body of time.

Then my friend Safdar Hashmi introduced me to Tufail Niazi of the Pakhawajia Gharana of Kapurthala, a school that had shifted to Pakistan at the time of the Partition of Punjab. The style was very different from the ones I knew, which were not reposeful enough for my liking.

Tufail saab’s singing felt like the first rays of the sun grazing the earth.

My engagement with theory was influenced largely by Gilles Deleuze, a French postmodern thinker. Deleuze dealt with the idea of time as duration, which has been the key to my practice as a Sufi singer. If my performance does not create a concrete duration then the whole experience is not worth it. I don’t want to live one moment to another. I want to create a larger body of time.

Deleuze, the philosopher and Tufail saab, an unlettered bard with impeccable grounding in classical training, intersected very interestingly for me.

Mani Kaul, the filmmaker and a dear friend, dealt with the notion of how the uninterrupted body of time would emerge through the cinematic image. Watching Uski Roti at its very first screening in 1969 unsettled me. People were derisive, saying it took too long to move from one shot to another. Film time is assembled time. You shoot, cut and an assemblage of images becomes a sequence. Here image and real time almost coalesced.

Through Kaul, I was introduced to Ritwik Ghatak, who worked with epical time rather than Kaul’s image, which was a direct, though not denuded, image of time. Ghatak traverses the space of cinema with the threads of memories, which are not arranged in a continuum, but scattered across a sort of proto-history.

Memories are not fully available, but come to you in a surge of epical melos. His compassionate treatment of the passage of time in Meghe Dhaka Tara is the ultimate test of sensitivity, and I cry every time I watch the film. Ghatak became a huge point of reference for me.

The influences of my formative years taught me to treat time as something that becomes available immediately to you, rather than something separate that is awe-inspiring, but not yours. I wanted to make time my own.

I find a resonance in the various registers of history. When I visit our Sufi past(s), I don’t do so from a position frozen in time, but from the now. When I read Rumi saying, “I am not from the world, not from beyond, not from heaven and not from hell,” I think of John Lennon’s Imagine: “Imagine there’s no heaven / It’s easy if you try / No hell below us / Above us only sky.” Without this transaction we would be terribly ritual-ridden.

I see myself as a traveller, which is a very personal experience but creates a sense of community. If I travel to the south for a performance, I suddenly feel like singing Purandara Dasa, who wrote in Kannada. In Gujarat, I have always sung in Punjabi. People may not understand, but the response is enormous. When you enter a sound, the meaning of the text is transmitted differently. The burden of the text is shrugged, and through the sound you begin to construct memory and personal experiences, a new sense of time.

Think of the finest singers who have been able to, in the classical sense, get involved with time. Abida Parveen achieves a state of ecstasy completely her own within a five-minute performance. She was trained by Ustad Salamat Ali Khan, but there are no traces of his influence in this part of her singing.

That is greatness.

There are three stages of singing in Sufism. You begin to feel the presence of something. The presence begins to overwhelm you. You become one with it.

I am fascinated by the way Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan enters a note. The way he approaches the vowel sound -- the ‘e’ and the ‘a’ -- is unique. Singers who try to be sensational have no idea of how the threshold of the vowel sound has to be tackled. You have to create a house for it, and then leave.

People might say Kailash Kher is like Khan, but it is a facile comparison. Khan comes from a tradition like Parveen, people who are insiders of a belief driven school of training. Those who emulate them are outsiders, uninvolved. They are passable singers, but good singing is not enough. We have the technical know-how and resources, but not the ‘aqeeda’, without which you cannot create magic.

It cannot be deliberate.

When you listen to Zakir Hussain playing the same theka 40 times, there is hardly any variation, but you realise something has happened.

Sufi music is that unfettering experience. It allows me to access the idea of obsessive returns to the same phrase. This principle of duplication in music and literature creates a meaning that is effusive and overpowers you into a trance.

Madan Gopal Singh is a Sufi singer-writer and film theorist. He was part of the musicians’ residency Sound Res at San Ceasario, Italy (2005), and participated in the Bonn Biennale (2006). He teaches English Literature at the University of Delhi and has written the National Award-winning film Rasayatra.

Courtesy: Tehelka

October 14, 2013