Current Events

Is India on a Totalitarian Path?

Part II

Interview with ARUNDHATI ROY

Continued from yesterday…

PART II

YESTERDAY: The RSS, a violent and terrorist Hindu right-wing organization, was found responsible for the assasination of Mohandas Gandhi, and was banned in India.

ROY: Modi started out as a worker for the RSS. He, of course, came into great prominence in 2002, when he was already the chief minister of Gujarat but had been losing local municipal elections.

And this was at the time when the BJP had run this big campaign in -- they had demolished the Babri Masjid, this old 14th century mosque, in 1992. But they were now saying, "We want to build a big Hindu temple in that place." And a group of pilgrims who were returning from the site where this temple was supposed to be built, the train in which they were traveling, the compartment was set on fire, and 58 Hindu pilgrims were burned.

Nobody knows, even today, who set that compartment on fire and how it happened. But, of course, it was immediately, you know, blamed on Muslims. And then there followed an unbelievable pogrom in Gujarat, where more than a thousand people were lynched, were burned alive. Women were raped. Their abdomens were slit open. Their fetuses were taken out and so on. And not only that --

GOODMAN: These were Muslims.

ROY: These were Muslims, by these Hindu mobs. And it became very clear that they had lists, they had support. The police were, you know, on side of the mobs. And, you know, 100,000 Muslims were driven from their homes. And this happened in 2002, this was 12 years ago.

And subsequently, they have been -- you know, the killers themselves have come on TV and boasted about their killing, come on -- in sting operations. But the more they boasted, the more it became -- I mean, for people who thought other people would be outraged, in fact it worked as election propaganda for Modi.

And even now, though he took off his sort of saffron RSS headgear and his red tikka (Hindu ceremonial smudge on the forehead) and then put on a sharp suit and became the development chief minister, and yet, you know, when -- recently, when he was interviewed by Reuters and asked whether he regretted what happened in 2002, he more or less said, "You know, I mean, even if I were driving a car and I drove over a puppy, I would feel bad," you know? But he very expressly has refused to take any responsibility or regret what happened.

SHAIKH: But that’s one of the extraordinary things that you describe in the book, is that following liberalization and the growth of this enormous middle class, 300 million, there was a simultaneous shift, gradual shift, to a more right-wing, exclusive, intolerant conception of India as a Hindu state.

So, simultaneously, this class embraces neoliberalism, the neoliberalism in India, and also a more conservative Hindu ideology. So can you explain how those two go together, and how in fact, along with what you said now about Modi, how that might play out in this election?

ROY: You know, whenever I speak in India, I say that in the late '80s what the government did was they opened two locks. One was the lock of the free -- of the market. The Indian market was not a free market, not an open market; it was a regulated market. They opened the lock of the markets.

And they opened the lock of the Babri Masjid, which for years had been a disputed site, you know, and they opened it. And both those locks -- the opening of both those locks eventually led to two kinds of totalitarianisms.

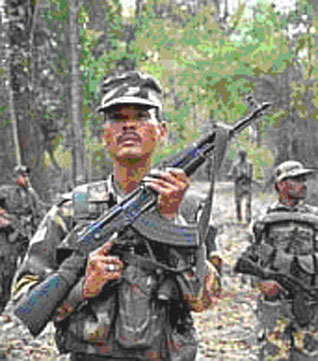

One -- and they both led to two kinds of manufactured terrorisms. You know, so the lock of the open market led to what are now being described as the Maoist terrorist, which includes all of us, you know, all of us. Anybody who's speaking against this kind of economic totalitarianism is a Maoist, whether you are a Maoist or not.

And the other, you know, the Islamist terrorist. So, what happens is that both the Congress party and the BJP has different prioritizations for which terrorist is on the top of the list, you know? But what happens is that whoever wins the elections, they always have an excuse to continue to militarize.

SHAIKH: So the two main parties who are contesting this election are Congress, which is the ruling party now, and the BJP, the Bharatiya Janata Party, of which Narendra Modi is the head. And you’ve said that the only difference between them is that one does by day what the other does by night, so as far as these policies are concerned, you can see no difference, irrespective of who wins.

ROY: When it comes down to the wire, I agree with what I’ve said. And yet, you know, there is something to be said for hypocrisy, you know, for doing things by night, because there’s a little bit of tentativeness there; there isn’t this sureness of, you know, "We want the Hindu nation, and we want the rule of the corporations," and so on.

But, yes, I mean, what happens is that everybody knows. It’s like whoever is in power gets 60 percent of the cut, and whoever is not in power gets 40 percent. That’s how the corporates work. They have enough money to pay the government and the opposition. And all these institutions of democracy have been hollowed out, and their shells have been placed back, and we continue this sort of charade in some ways.

GOODMAN: Arundhati Roy continues with a reading from her new book, “Capitalism: A Ghost Story.”

ROY: "Which of us sinners was going to cast the first stone? Not me, who lives off royalties from corporate publishing houses. We all watch Tata Sky, we surf the net with Tata Photon, we ride in Tata taxis, we stay in Tata Hotels, sip our Tata tea in Tata bone china and stir it with teaspoons made of Tata Steel. We buy Tata books in Tata bookshops. We eat Tata salt. We are under siege.

"If the sledgehammer of moral purity is to be the criterion for stone-throwing, then the only people who qualify are those who have been silenced already. Those who live outside the system; the outlaws in the forests or those whose protests are never covered by the press, or the well-behaved dispossessed, who go from tribunal to tribunal, bearing witness and giving testimony."

But this -- you know, I’m talking about this because, as I said, for the poor, India has the army and the paramilitary and the air force and the displacement and the police and the concentration camps. But what are you going to do to the rest?

And there, I talk about the exquisite art of corporate philanthropy, you know, and how these very mining corporations and the people who are involved in, really, the pillaging of not just the poor, but of the mountains, of the rivers, of everything, are now -- have now turned their attention to the arts, you know?

So, apart from the fact that, of course, they own the TV channels and they fund all of that, they, for example, fund the Jaipur Literary Festival -- Literature Festival, where the biggest writers in the world come, and they discuss free speech, and the logo is shining out there behind you.

But you don’t hear about the fact that in the forest the bodies are piling up, you know? The public hearings where people have the right to ask these corporations what is being done to their environment, to their homes, they are just silenced. They are not allowed to speak. There are collusions between these companies and the police, the Salwa Judum, which I was talking about earlier.

And, the whole -- the whole way in which capitalism works is not just as simple as we seem -- as it seems to be. We don’t even understand the long-term game, you know?

And, of course, America is where it began, in some ways, with foundations like the Rockefeller and the Ford and the Carnegie. And what was -- what was their idea? You know? How did it start? It was -- now it seems like part of your daily life, like Coca-Cola or coffee or something, but in fact it was a very conceptual leap of the business imagination, when a small percentage of the massive profits of these steel magnates and so on went into the forming of these foundations, which then began to control public policy.

They really were the people who gave the seed money for the U.N., for the CIA, for the Foreign Relations Council. And how did they then -- when U.S. capitalism started to move outwards, to look for resources outwards, what roles did the Rockefeller and Ford and all these play? You know, how did -- for example, the Ford Foundation was very, very crucial in the imagining of a society like America which lived on credit, you know?

And that idea has now been imported to places like Bangladesh, India, in the form of microcredit, in the form of -- and that, too, has led to a lot of distress, to a lot of killing, this kind of microcapitalism.

GOODMAN: These corporate foundations you talk about, how are they evidenced in India?

ROY: Which ones? You mean --

GOODMAN: Like the Ford, the Carnegie, the Rockefeller.

ROY: Rockefeller. Well, you know, I mean, in this, I’ve talked about the role not just in India, but even in the U.S. For example, how do they even -- how do they deal with things like political people’s movements? How did they fragment the civil rights movement? I’ll just read you a part about what happened with the civil rights movement.

“Having worked out how to manage governments, political parties, elections, courts, the media and liberal opinion, the neoliberal establishment faced one more challenge: how to deal with the growing unrest, the threat of ’people’s power.’ How do you domesticate it? How do you turn protesters into pets? How do you vacuum up people’s fury and redirect it into a blind alley?

“Here too, foundations and their allied organizations have a long and illustrious history. A revealing example is their role in defusing and deradicalizing the Black Civil Rights movement in the United States in the 1960s and the successful transformation of Black Power into Black Capitalism.

“The Rockefeller Foundation, in keeping with J.D. Rockefeller’s ideals, had worked closely with Martin Luther King Sr. (father of Martin Luther King Jr). But his influence waned with the rise of the more militant organizations -- the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panthers.

The Ford and Rockefeller Foundations moved in. In 1970, they donated $15 million to 'moderate' black organizations, giving people grants, fellowships, scholarships, job training programs for dropouts and seed money for black-owned businesses. Repression, infighting and the honey trap of funding led to the gradual atrophying of the radical black organizations.

"Martin Luther King made the forbidden connections between Capitalism, Imperialism, Racism and the Vietnam War. As a result, after he was assassinated, even his memory became toxic to them, a threat to public order. Foundations and Corporations worked hard to remodel his legacy to fit a market-friendly format.

The Martin Luther King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, with an operational grant of $2 million, was set up by, among others, the Ford Motor Company, General Motors, Mobil, Western Electric, Procter & Gamble, U.S. Steel and Monsanto. The Center maintains the King Library and Archives of the Civil Rights Movement. Among the many programs the King Center runs have been projects that work -- quote, 'work closely with the United States Department of Defense, the Armed Forces Chaplains Board and others,' unquote. It co-sponsored the Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture Series called -- and I quote -- ’The Free Enterprise System: An Agent for Non-violent Social Change.’"

It did the same thing in South Africa. They did the same thing in Indonesia, you know, with the -- General Suharto’s war, which all of us now know about because of “The Act of Killing in Indonesia.”

And very much so in even places like India, where they move in and they begin to NGO-ize, say, the feminist movement, you know?

So you have a feminist movement, which was very radical, very vibrant, suddenly getting funded, and not doing -- it’s not that the funded organizations are doing terrible things; they are doing important things. They are doing -- you know, whether it’s working on gender rights, whether it’s with sex workers or AIDS. But they will, in their funding, gradually make a little border between any movement which involves women, which is actually threatening the economic order, and these issues, you know?

So, in the forest, when I went and spent weeks with the guerrillas, you had 90,000 women who were members of the Adivasi Krantikari Mahila Sangathan, this revolutionary indigenous women’s organization, but they are threatening the corporations, they are threatening the economic architecture of the world, by refusing to move out of there. So they’re not considered feminists, you know?

So how you domesticate something and turn it into this little -- what in India we call paltu shers, you know, which is a tame tiger, like a tiger on a leash, that is pretending to be resistance, but it isn’t.

SHAIKH: But before we conclude, Arundhati Roy, you have not written a novel -- you’re probably sick of being asked this question -- since “The God of Small Things.” And you said that you may return to novel writing now as a more subversive way of being political. So could you either talk about what you intend to write or what you mean by that?

ROY: I’ve been writing straightforward political essays for 15 -- almost 15 years now. And often, they are interventions in a situation that seems to be closing down, you know, whether it was on the dam or whether it was about privatization or whether it was about Operation Green Hunt.

And I feel now that, you know, in some ways, through those very urgent political essays, which are all interconnected -- they are not just separate issues, they are all interconnected, and they are, together, presenting a worldview. Now I feel that I don’t have anything direct to say without repeating myself, but I think what -- you know, that understanding, which was not just an understanding I had in the past and I was just preaching to my readers, you know; it was I was learning as I wrote and as I grew.

And I feel that fiction now will complicate that more, because I think the way I think has become more complicated than nonfiction, straightforward nonfiction, can deal with. You know, so I need to break down those proteins and write in a way which -- I don’t have to write overtly politically, because I don’t believe that -- I mean, I think what we are made up of, what our DNA is and how we are wired, will come out in literature without making a great effort to raise slogans. And --

GOODMAN: Before we end, and before you come out with this next novel that we’ll ask you to read next time when you come to the United States, I was wondering if you could read from an earlier essay. It’s an excerpt that you read at the New School, when hundreds of people came out to see you here recently.

ROY: Well, it was -- it was really the first -- in a way, the first political essay I wrote, anyway, after “The God of Small Things“, and it was an essay called "The End of Imagination," when the Indian government conducted a series of nuclear tests in 1998.

"In early May (before the bomb), I left home for three weeks. I thought I would return. I had every intention of returning. Of course, things haven’t worked out quite the way I planned." Of course, by which I meant that India just wasn’t the same anymore.

“While I was away, I met a friend of mine whom I have always loved for, among other things, her ability to combine deep affection with a frankness that borders on savagery.

“’I’ve been thinking about you,’ she said, 'about “The God of Small Things” -- what's in it, what’s over it, under it, around it, above it ...’

“She fell silent for a while. I was uneasy and not at all sure that I wanted to hear the rest of what she had to say. She, however, was sure that she was going to say it. 'In this last year,' she said, 'less than a year actually -- you've had too much of everything -- fame, money, prizes, adulation, criticism, condemnation, ridicule, love, hate, anger, envy, generosity-- everything. In some ways it’s a perfect story. Perfectly baroque in its excess. The trouble is that it has, or can have, only one perfect ending.’ Her eyes were on me, bright with a slanting, probing brilliance. She knew that I knew what she was going to say. She was insane.

"She was going to say that nothing that happened to me in the future could ever match the buzz of this. That the whole of the rest of my life was going to be vaguely unsatisfying. And, therefore, the only perfect ending to the story would be death. My death.

“The thought had occurred to me too. Of course it had. The fact that all this, this global dazzle -- these lights in my eyes, the applause, the flowers, the photographers, the journalists feigning a deep interest in my life (yet struggling to get a single fact straight), the men in suits fawning over me, the shiny hotel bathrooms with endless towels -- none of it was likely to happen again. Would I miss it? Had I grown to need it? Was I a fame-junkie? Would I have withdrawal symptoms?

“I told my friend there was no such thing as a perfect story. I said in any case hers was an external view of things, this assumption that the trajectory of a person’s happiness, or let’s say fulfillment, had peaked (and now must trough) because she had accidentally stumbled upon 'success.' It was premised on the unimaginative belief that wealth and fame were the mandatory stuff of everybody’s dreams.

“You’ve lived too long in New York, I told her. There are other worlds. Other kinds of dreams. Dreams in which failure is feasible. Honorable. And sometimes even worth striving for. Worlds in which recognition is not the only barometer of brilliance or human worth. There are plenty of warriors that I know and love, people far more valuable than myself, who go to war each day, knowing in advance that they will fail. True, they are less 'successful' in the most vulgar sense of the word, but by no means less fulfilled.

“The only dream worth having, I told her, is to dream that you will live while you’re alive and die only when you’re dead.

“’Which means exactly what?’

"I tried to explain, but didn’t do a very good job of it. Sometimes I need to write to think. So I wrote it down for her on a paper napkin. And this is what I wrote: To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance. To never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around you. To seek joy in the saddest places. To pursue beauty to its lair. To never simplify what is complicated or complicate what is simple. To respect strength, never power. Above all, to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget."

CONCLUDED

[Courtesy: Democracy Now. Edited for sikhchic.com]

April 13, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), April 13, 2014, 10:59 AM.

Strange country, where there are 360 million gods and goddesses who constantly demand animal and human sacrifices, we are now plagued by RSS, BJP and other and Hindu extremists ...