1984

The Man From Rajoana:

Part I

by AMANDEEP SINGH SANDHU

The death sentence of Balwant Singh Rajoana was stayed a few weeks ago, after he waited for 17 years on death row, on the eve of the scheduled hanging. It came with the intervention of Beant Singh's successor, the current Akali Dal chief minister of Punjab, with the president of India.

Shortly after the stay, I embarked on a personal journey.

I wanted to know what - in the intervening years since Balwant Singh act of personal sacrifice two decades ago - has changed in Balwant Singh’s village and what has stayed the same. I wanted to see what, if freed and allowed to return home, would Balwant Singh find in his village.

* * * * *

Sikhism teaches that every one, man or woman, should be willing to give one’s life to protect the oppressed and the downtrodden.

The sacrifice vindicates one as a martyr, a hero.

But what happens if the sacrifice were not to be of life but of time? If the sacrifice meant an unending wait and in the meantime the soldier has to live, and has to acknowledge the changes in society and yet keep one’s stance alive and meaningful?

Balwant Singh Rajoana, convicted - on the basis of

his voluntary confession - as an accessory for the assassination of the

chief minister of Punjab, Beant Singh, is a story that illustrates this

dilemma. He could have been the actual assassin and died in the

execution of his action, but has now been on the death row for the last

17 years.

Recently, after worldwide outrage and protests, his hanging was stayed by the Court.

At the end of the 1980s the situation in Punjab was so complex that no one ever imagined things could go back to normal. That is when the Punjab Police, under the leadership of its chief K.P.S. Gill, conducted wholesale massacres of innocent youth across the state - their only crime that they were young Sikh men, and thus potential recruits to a separatist cause!

With the backdrop of continuing militancy triggered by, and directed against gross human rights violations by the state, the police and para-military personnel saw it as an oportunity to seek promotions and benefits, by "mopping up" the country-side - a term coined for picking up innocent Sikh boys and young men from their homes and killing them in fake encounters.

No one can cite the numbers of the innocent killed ... estimates vary from 20 thousand to 50 thousand. But the militancy - which had by now developed into a resistance movement and a separatist cause, now had three groups of players: the police, the resistance, and the people.

Innocent boys and young men, now unaccounted for in the tens of thousands, bore the brunt of it all.

That is when two Punjab Police constables, Balwant Singh and his colleague, Dilawar Singh, along with others including the Babbar Khalsa member Jagtar Singh Hawara, planned to assassinate Beant Singh. The intent was to shock the state machinery into stopping the wholesale murder of innocents.

A coin was tossed and Dilawar Singh was chosen to act as the human bomb. In the explosion in front of the Chandigarh Secretariat, Beant Singh was assassinated. 17 others died.

Balwant Singh was the stand-by, scheduled to go into action if the first attempt failed.

He was arrested in December 1995. He immediately confessed to his role. His stance was that it was an act of conscience, which would not permit him to deny his own role in it.

At trial, Balwant Singh readily acknowledged his actions. He refused to contest the prosecution's charges, challenge ts evidence, engage a lawyer or accept a court-appointed lawyer.

Instead, he spoke from the dock and from the prison through statements to the courts and letters to the judges. He described the deep wounds on the Sikh psyche caused by the state's despoiling of the Golden Temple by the Indian army during Operation Bluestar. He spoke of the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms - actively encouraged and facilitated by the Indian state - when thousands of Sikhs were burnt alive, mutilated and left for carrion, funeral rites denied, when women were dishonoured, the youth emasculated and homes burnt.

He demanded that the Chief

Justice first determine who were the terrorists: those who did these

acts or those who defended the victims?

When convicted by the Court, Balwant Singh refused to appeal the death sentence and instructed his friends and family not to

petition the government for mercy. He also turned away similar offers from social, religious and political groups.

In an open letter to the media, Balwant Singh proclaimed: ‘Asking for mercy from them (Indian courts) is not even in my distant dreams.’

* * * * *

The village Rajoana is about 2 km off the state highway. The village starts, like most Punjab villages, with a pond but its houses are aligned towards the left and not on the road, so one crosses the village too quickly.

I passed them by and then stopped at a brick kiln where I met Amarjit and asked him if the village was indeed the one I sought. He answered in the affirmative and I asked in jest, ‘Are the gurdwaras in your village divided on lines of caste, as are most of them now-a-days in Punjab?’

‘Brother,’ said Amarjit, ‘The more

gurdwaras we build, the more we divide our community. We have four but

that is because of the grace of Guru Gobind Singh and not because we

discriminate on lines of caste. All are welcome.’

That was reason enough for me to have tea with him. He tells me that the

literacy rate in the 4000 strong village is 100 per cent. They have a

middle school and then kids go to high school three km away. The village

grows two crops: wheat and rice. No canal or river touches the village,

so everyone depends on ground water.

Though now, equipped with submersible pumps, the water table has fallen to 250 feet.

A farmer with 15 acres is considered to be a rich man and since most families are not split over land, farming remains a viable option. The sugarcane plantation stopped when the sugar mill at Jagraon shut down.

People indulge in liquor and opiates but not in synthetic drugs or heroin or smack. Hence no one from these villages has ever been to a detoxification camp or been treated for addiction. Hardly anyone has migrated abroad and there is no craze for Canada or Italy.

Interestingly, since the mid-90s, the state assembly constituency in which the village falls, Raikot, and the central constituency, Fategarh Sahib, has always voted in opposition to the parties that gained power in either the State Assembly or the Centre.

‘No politician, except for

Simranjeet Singh Mann, has ever stepped into our village. Forget

expressing solidarity with Balwant Singh, they do not even come here for

campaigning. As if our village has done something they can’t even

comprehend.’

I felt, maybe that is why this sort of self-governed village remains an island in the murky waters of Punjab and India today.

"Jagdeep just announced his wish to be sarpanch (head of the village council) and no one opposed him. We always elect our

panchayat (village council) like that ... through consensus.’

As is the custom, Amarjit Singh takes the name of his village as his surname but his birth surname is Natt.

Similarly, Balwant Singh Rajoana was born Balwant Singh Natt.

* * * * *

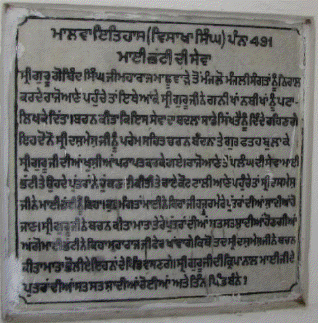

The Natts of Rajoana Kalan trace back their history to a woman known as Mai Bhatti. She lived during the life and times of Guru Gobind Singh.

The legend relates to the time the Guru was engaged in challenging the tyrants of the region - the ruling Mughals and the petty Hindu rajas that fed off them. While on his way from Chamkaur Sahib and Machhiwada, he came to the village where Mai Bhatti lived with her three sons. Spent and exhausted and without even a horse, he came upon the family and requested the sons to find one for him.

He spent the night there and the next morning Mai Bhatti, together with her three sons, carried the Guru on a manji (a small light cot). Once awake, the Guru noticed that one end of the manji was dipping lower than the other three, but could not see the reason for this. Before long, he realized that it was because the mother, Mai Bhatti, was supporting that end of the manji on her frail shoulders.

Guru Gobind Singh was moved by their devotion and blessed Mai Bhatti and her family in gratitude for their support and commitment.

Later, when he asked Mai Bhatti if he could help them in any way, she merely asked for his blessings so that each of her sons would soon find a bride and settle down. Guru Gobind Singh was amused by the simplicity of her wishes and asked if he could help materially, with money, for example. But all she wanted was that each of her sons be well-settled and flourish.

The Guru, in his munificence, showered them with his blessings.

Before long, the story goes, each son prospered and founded a village.

The three villages, peopled by Mai Bhatti's descendants, thrive to this day: Rajoana Kalan (the main village); Chotta Rajoana (small Rajoana) also known officially as Rajoana Khurd; and the village of Tugal.

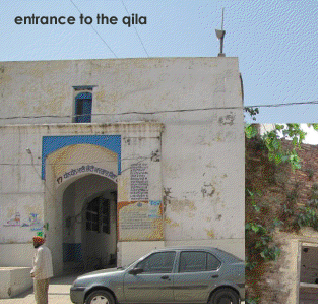

Initially all the families and descendants of Mai Bhatti’s sons lived together within the Qila (fort).

The current sarpanch of Rajoana Kalan, Jagdeep Singh, still lives in the Qila.

* * * * *

One of the residents of Rajoana is a man named M. Khan.

During the partition of Punjab and India in 1947, Jagdeep’s father had encouraged Khan’s father to stay back at the village, promising him and his beleagured co-religionists safety. Khan tells how even at the peak of communal violence, his family and the other Muslims in the village had felt and remained absolutely safe amongst its Sikh residents.

"I have been seeing Balwant since he was a young kid. A very quiet boy. We are all very proud of him. See the flags in the village?" points out Khan.

It was the day exactly a week

after Balwant Singh was to be hanged. Each house and each tree in the

village carries the Nishaan flag. The hot winds have not yet blown the

flags to bits.

Jagdeep’s mother tells me how the annual Mai Bhatti langar has now

become a big fair, a mela. Her daughter is trying to find more details

on the Mai Bhatti story and maybe they will produce a CD depicting the

saga from Guru’s life and how their villages are linked.

"Everyone in our village gets married," she says. "We are blessed."

But one man stayed a bachelor.

Balwant Singh never married.

TO BE CONTINUED TOMORROW ... Please CLICK here.

Amandeep Singh Sandhu is the author of Sepia Leaves and the upcoming novel Roll of Honour, a novel on the split loyalties of a Sikh adolescent in a military school during the years of state oppression, and the resulting resistance movement and militancy in Punjab. Both books are by Rupa Publications.

April 17, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Karam Singh (New Delhi, India), April 17, 2012, 1:05 PM.

An excellent piece - accurate, thought-provoking, courageous ... Can't wait to read the rest of it tomorrow.

2: Rosalia (Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.), April 17, 2012, 1:49 PM.

What an insightful and well crafted piece! Looking forward to part II.

3: Niranjan Kaur (Chandigarh, Punjab), April 17, 2012, 1:57 PM.

It is indeed time for our intellectuals - our writers, playwrights, poets, artists, singers, choreographers, filmmakers, teachers, historians, academics, performers, dancers - to start telling our stories, especially relating to 1984. So far, we have been given mere propaganda and a distorted view of what actually happened. The truth needs to be told. Amandeep's piece is a bit of fresh air ... we need more from him and those who have the skills and courage to articulate the truth. Thank you, Amandeep! All power to you!

4: Manjit Kaur (Maryland, U.S.A.), April 17, 2012, 2:27 PM.

A wonderful piece. Can't wait for part II. It's very important for today's youth to understand the origins and the lifestyles behind our heroes like Balwant Singh.

5: Jasjeet Singh (U.S.A.), April 17, 2012, 2:48 PM.

An island in the murky waters, indeed. Like Guru Nanak's lotus, surrounded by filth, yet above it all. Just shows that leaders will rise from the most unexpected quarters. Our task as a community is to be ready for them. We aren't yet. We need to work at it diligently, steadily, efficiently, persistently ... until the time is ripe.

6: Surjit Singh (U.S.A.), April 17, 2012, 7:25 PM.

The last line gave me goosebumps. I heard my heart beat. Very well crafted.

7: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), April 17, 2012, 11:05 PM.

When governments play politics with peoples' lives, the result is the same! Righteous humans will rise up and take action to stop tyranny and senseless, mindless violence.

8: Raminder Singh (New Delhi, India), April 18, 2012, 8:12 AM.

Very informative and thought-provoking. Anxiously waiting for Part II. Such facts about Sikhs, their religion, history, etc., should be highlighted more aggressively to the world. Thanks, Amandeep, for your excellent work.

9: Amrinder Singh (New Delhi, India), April 19, 2012, 1:17 AM.

Very inspiring. Thanks for bringing this to all of us.

10: Sukhindarpal Singh (Penang, Malaysia), April 19, 2012, 8:20 AM.

Thank you for taking me to Rajoana village.

11: Harpreet Kaur (Singapore), May 15, 2012, 11:20 AM.

Really looking forward to reading Part 2 and also the kind lady who will be producing a CD about Guru Gobind Singh and how Mai Bhatti experienced his presence. Thank you for these wonderful articles. Your website and its content has always inspired me. Thank you.