1984

8T4 - Part I

JASPREET SINGH

The first stories I heard as a child were the stories of Partition. I was most taken by the ones narrated by my maternal grandfather.

He had studied botany and chemistry at Government College, Lyallpur, and later attended teachers training college. By the time I was born, he had retired as the principal of a high school in East Punjab and lived not in Lyallpur (Pakistan) but in Ludhiana (India).

“Do you know the English word for ghanta-ghar?” he asked in Punjabi.

“Clock tower,” I responded.

“No,” he said. “Ghanta-ghar when translated literally means the house of hours.”

Mesmerized by his words, I would insist on sleeping in his room whenever we visited our grandparents during school holidays. Most cousins didn’t want to sleep in that room. Grandfather slept with the lights on, and he woke up early in the morning. He suffered from chronic bronchitis (after a long-ago trip to a hill-station) and occasionally lapsed into yoga-inspired breathing exercises. Plus the room carried the mild odour of a chemical laboratory. In the corner cupboard there were four or five dark-brown bottles of chemicals, a Bunsen burner, and an optical microscope.

My scientific grandfather would wake up at 4:30 sharp, recite the Japji, and soon afterwards hold dialogues between God and Darwin. Halfway into the dialogues he would slip into a Sufi-style swoon.

Nanak nadari nadar nihal. Nanak nadari nadar nihal.

God would win the argument in the end, but the next day Darwin would challenge God once again.

We called him Bhapaji, and so did everyone else. Even our grandmother called him Bhapaji. She would wake up at 4:25 in the morning (without using an alarm clock), make Bhapaji a cup of cardamom tea, deliver the trembling tray (along with grooved desi-style biscuits) to his room, and then go back to sleep till seven or so before she started kitchen.

Right after his God-and-Darwin dialogues, Bhapaji would step out, do a neem datun by the guava tree in the courtyard. More breathing exercises would follow, and he would hurriedly scan through the Tribune. During a light breakfast of milk with honey, toast, and fruit, he would feel more relaxed and he would start interacting with us and telling us stories.

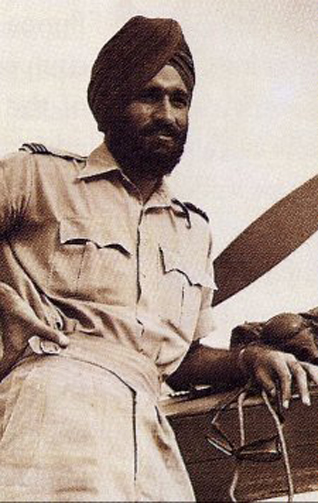

Most began like ordinary stories for children, with birds and planes, and skilful pilots flying Wapitis and Spitfires. Sometimes the pilot, sensing trouble in a foreign land, would land like a bird on a tree.

The pilot in Bhapaji’s stories had only one name, Mehar Singh. With looping gestures Bhapaji would exaggerate Mehar Singh’s daredevilry and mimic machine sounds. Every word he uttered beguiled us children. And if grandmother said, “Enough now, you have already told the story many times,” he would shut her up with four softly uttered words: she is so unscientific.

He would explain then how a bird flies and how a plane flies and slowly the story would swirl into the story of our family's “flight” from across the border.

When I was only one and very sick, my mother told me, Bhapa ji would lift me up and walk back and forth in the room reciting poetry in Punjabi or Urdu or English. Keats, Ghalib, Waris Shah. He would do so for the sake of anyone present in the room, but also for my sake, and either by the sheer power of his words or the fact that I was glued to his heart or was it the fact that he was always walking -- I would stop crying.

Mother said when I was born in Brown Hospital, Ludhiana, Bhapaji took me from the nurse and with the tip of his little finger deposited a tiny drop of honey on the tip of my tongue. This is known as gurti in Punjabi, and parents always choose someone who is a perfect role model to administer gurti. My mother so much wanted me to become like him.

Every summer during school holidays my mother would take us to Ludhiana to visit Bhapaji. Summers are extremely hot in Ludhiana, the handloom city, the cycle-parts city, the so-called Manchester of India, but we managed with ceiling fans and a “desert cooler.”

Each one of the rooms in his house was unique, as if it belonged to a slightly different imponderable epoch. He didn’t have enough money to build the house all at once, so he kept adding a room every five years or so.

The room where he slept, and stored his little laboratory, was the first room he built in new India after losing an entire house to Partition, and it was in this room he would tell me about the canal colonies on the other side of the border, and a Daedalus-like figure flying over the icy peaks of the Hindu Kush and the Karakorams.

Once during a campaign in Afghanistan, Mehar Singh’s Wapiti was damaged heavily and signalmen at HQ feared the worst. But Mehar Singh managed to land on the ledge of a sheer cliff, quickly separated himself from the wreckage, and just a day later reported back to his unit and was flying again.

In 1947, when the country was divided, my mother was only three years old. She was born in the same fabled Lyallpur, 120 miles from Lahore, the big cultural and historical centre. Lyallpur was a young city, one of the youngest in British-occupied India. The land was semi-arid there, and until the 1880s no one wanted to settle in that part of Punjab.

The region started growing when British engineers built three canals connecting the region to the Chenab River -- one of the most ambitious irrigation schemes at the turn of the century. The colonial administrators saw these “canal colonies” as one of their biggest achievements.

Lyallpur, a so-called “model town,” was named after a civil servant and a sort-of translator, Charles James Lyall. Downtown was eight luminous market lanes (as if the British flag, the Union Jack) converging toward a still point -- the giant clock-tower, the ghanta-ghar.

Several times in my adult life I have tried to reconstruct the complete story of our family’s flight, but the best reconstruction comes from my mother.

In Lyallpur in the 1940s, your grandfather (now a married man with children) taught at the government school. Evenings he would supplement his income by giving tuitions.

Soon his tutoring talent spread far and wide. One day a lady arrived on a horse buggy from a village close by and persuaded Bhapaji to teach her daughter. “My tonga will take you to the village and bring you back.” The daughter’s elder brother was none other than the legendary pilot Mehar Singh. The benign matriarch of a figure would not take no for an answer.

Mehar Singh’s sister was weak in chemistry, and Bhapaji started teaching her Dalton and his atoms. Over time the two families grew very close.

Then Partition was announced in 1947 and all hell broke loose.

Bhapaji was convinced peace would return soon. The turmoil was temporary, he thought. But soon trains started arriving full of corpses. Curfew was imposed twenty-four hours. One stepped out at one’s own peril.

By September 15, most surviving Hindus and Sikhs in Lyallpur had moved to college campuses, which had been hurriedly transformed into camps. In all, there were four or five camps in the city, and things were going badly in all of them.

Then broke out the cholera.

Bhapaji fell sick. It was not cholera in his case, but the symptoms were similar.

On the fourth day, he slipped into the college prayer room and consulted the Holy Granth. He opened the book randomly and read: Ram Das sarovar nahtay sab utray paap kamatay.

Filled with hope, your grandfather returned to the room and announced, “By tomorrow we will end up in Amritsar.” People thought the teacher had gone crazy. Bhapaji repeated, “Tomorrow we will take the road to Amritsar.”

That evening two men started making inquiries about our family. They drove to all the camps in Lyallpur looking for “the teacher” and found us in that miserable camp. They were Air Commodore Mehar Singh’s brothers, and they drove our family on a military truck to the matriarch’s village.

“We will spend the night in the village,” they said. “Early in the morning we will drive to the airport.”

We thought we would be the first ones to fly. But the matriarch had carved out a different plan. She and her family would not fly until the entire village had been airlifted in that solitary Dakota. Mehar Singh did eleven or twelve sorties, and finally we flew very late in the evening on the last flight to Amritsar.

For a few months we stayed in a single room in a haveli in Amritsar. The haveli was “vacated” by a Muslim family. It was my elder brother’s, your uncle’s, duty to go to the Golden Temple every day and bring home all newly arrived friends and relatives. He was twelve years old then. One day he brought back a tearful surprise, Bhapaji’s father, who had started out from his village in District Toba Tek Singh a month earlier with a kafila. He was exhausted, underfed, and disoriented, and that night he slept in the huge third-floor room (“hall kamra”). In the middle of the night he woke up and walked out of the window, thinking it was a door, and fell three storeys below onto shards of glass.

The doctors bandaged his whole body. For three months he endured immense pain, then died.

I have often thought, perhaps the story of your great-grandfather’s death was different from the story the family told. Perhaps he knew the window was really a window and it was not a door. He had seen a lot. Your great-grandmother never made it. She died on the way.

Many years later in November 1984, when we were in Delhi and a “Hindu” mob created by the Congress Party passed by our block targeting Sikhs after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, we took refuge in our Hindu neighbour’s house. While hearing the acoustics of the mob, the barbaric slogans, the first person I thought about was my grandfather, and I thought of the pilot Mehar Singh. But I knew he would not come to rescue us.

We lived in R. K. Puram, Sector-3, close to the market. These were yellow-painted government flats. Before the mob appeared, my father had called his paramilitary regiment, requesting two security guards, but for some reason the guards were unable to make it on time.

We were the lucky ones. We were spared. Our bodies were spared fire, mutilation, and other things. Our things were not looted. After twenty minutes or so, the mob passed by. I recall hearing a couple of gunshots fired in the air, followed by a dead

silence, then loud racist and bloodthirsty slogans, but receding, as if a demonstration of the Doppler effect.

While we were in the neighbour’s house, it seemed as if we had entered a time warp. The size of those minutes is enormous in my mind. I was fifteen years old then. How many of my assumptions collapsed then. To this day I have not been able to articulate properly those few hours and the burned remains of buildings I saw later, and tiny ash particles floating in air. Even when the two security guards appeared at our doorstep I didn’t feel safe.

No matter how hard I try to forget those hours, they stand in my way. To this day I continue to “suffer from an event I have not even experienced” in its most extreme form.

Continued tomorrow ...

[Jaspreet Singh is a novelist, essayist, short story writer, and a former research scientist. His latest novel, Helium, will be published by Bloomsbury in 2013.]

[Courtesy: Brick]

June 23, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), June 23, 2012, 9:45 AM.

Jaspreet ji, thanks for the nostalgic trip to my beloved Lyallpur. I could literally touch the Govt. College, Lyallpur, next to the Dussehra Ground that was our regular playground. Talking of Mehar Singh, he was the hero for all of us in Lyallpur. Any airplane that strayed in the airspace of Lyallpur had to be commanded by Mehar Singh! I also remember his village: it was near the Khalsa College near the Waddi Nehar (Big Canal). As kids we had explored every inch of Lyallpur pre-1947, and it remains fossilized in our memory. I have never gone back as it wouldn't be the same Shangri-La. Even the name is wiped out. It was almost sacrilegious to have its unwilling conversion to the Islamic name.

2: Tanvinder Singh (Gurgaon, India), July 02, 2012, 11:48 AM.

Although I was born after the Partition of Punjab, I could still relate to the stories told to me by my grandfather about his home in undivided Punjab, now in Pakistan's Multan. Great writeup of warmth, relationship and love ... makes me miss my grandfather.

3: Abrar Rana (Lyallpur, Pakistan), November 20, 2013, 7:02 AM.

Jaspreet Singh ji: I am doing research on migration and violence in Lyallpur. I need information about the relations between Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims before the Partition. Did they have good relations or what kind of relations did they have? And, re the cultural life of Lyallpur; about the Partition and your journey to the newly created India. You can respond to me at royal_rana81@hotmail.com