Fiction

Erotic Stories For Punjabi Widows:

A New Novel By Balli Kaur Jaswal

A Book Review by STEPHANIE SHAPIRO

EROTIC STORIES FOR PUNJABI WIDOWS, by Balli Kaur Jaswal, Harper Collins, 2017. Hardcover, English & Punjabi, 320 pages. ISBN-10: 000820988X; ISBN-13: 978-0008209889.

A former co-worker who learned bare-knuckle politics in Boston during the Kennedy years had a little tradition he (may or may not have) observed when leaving one job for another: “Leave a few little bombs ticking here and there, then sit back and watch as they go off.”

“Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows” qualifies as a literary ticking bomb.

As middle-schoolers have said, “It’s da bomb,” and will be passed from hand to hand, raising havoc all the way. Author Balli Kaur Jaswali left in all the juicy parts, word for word as a Punjabi widow might – or might not – have written them. Ambiguity is no stranger to the world she creates.

Her name tells us she is a woman. A character explains that if a Sikh name contains “Kaur,” it belongs to a girl or woman; “Singh” denotes a man. Other Sikh or Punjabi words or words from other languages remain untranslated, but not looking them up did not make the book any less entertaining. The words usually denote foods or items of clothing, so the reader can figure out what is being described, more or less. None of it hampers the plot.

One family’s “necessities from India” include Brylcreem, turban starch and Neem soap. The mother raises a fuss when a daughter is bold enough to purchase a bar of Yardley English Lavender Soap. We are in a world where nothing changes without plenty of resistance.

Before setting the mayhem in motion, Balli Kaur makes her characters very clear. They all stay true to character, whatever the author makes happen to them.

Heroine Nikki tends bar in a London tavern, not – repeat not – in the Punjabi section of town. A law-school dropout, she attends feminist protests with her friend Olive during school hours but her parents eventually find out that she has left the university. All hell breaks out and never stops till every loose end in the plot is tied up, including a little surprising twist about her father’s manner of death during a trip to India.

Nikki is appalled by her sister, Mindi, wanting to get married in a traditional, arranged process. But she helps Mindi anyway through the awkward steps of meeting prospective husbands and their families, even two candidates at a time.

To pay the rent on her flat above her place of employment, she agrees to teach a class in creative writing at a Punjabi community center in the heart of the ethnic enclave. The program supervisor, not very adept at English herself, misrepresents the curriculum. The class turns out to be illiterate Punjabi widows, ages from their 30s through 80-something. What they want to write is the ABCs, not anything creative.

This is where Balli leaves what nearly seemed to be heading toward a 1950s sitcom rehash and opens the curtain on the dark side of community life, with child marriage, domestic violence, arson and honor killing. Because she has treated her characters seriously, her plot is strong enough to support their challenges when a thuggish group of religious “police” begins to close in on them. Midnight telephone calls, commands to cover their heads near the religious center – seemingly unimportant details start accumulating. The mysterious “suicide” of a young Sikh woman darkens the picture even more.

What sets all this menace and challenge into motion is Nikki’s basic English class. The widows resist her first attempts at teaching creative writing, struggling with the English alphabet but wanting a topic that interests them, one that relates to their own lives. Definitely not cooking or embroidery. Of course, what else could it be but sex?

One at a time, they narrate their fantasies: what they had enjoyed during marriage or outside its bonds; what they had been deprived of; what they wished for in vain. Then they take the written “stories” home to study. Someone makes a photocopy that gets passed on to someone else and of course eventually to the violent “Brothers” religious gang. Piling plot-twists sky-high, Balli keeps the action, including raw violence, moving along, with enough surprises to hold the reader’s attention.

Just in case anyone’s interest flags, the sexy “stories” scatter throughout the book: the language is slightly prim, the anatomy correct. The widows tell what they know. Nowhere does the author play any cheap literary tricks, telling the straight story, however awkward it may make a character’s situation.

Balli captures the texture of family life and community interactions in the details. What the furniture feels like, when to wash the sheets, which nail polish is popular with which social class, what makes pub life boring. We learn that, at least in the community created for this novel, Sikh widows do not remarry or even date. They wear distinctive clothing, white that sometimes goes gray around the edges. One of the students is not even a widow; she lies to cover embarrassment about her ailing husband running away with his nurse. Yes, of course, she takes him back, but for how long?

Nikki is no airhead. When the class office is vandalized, she is too canny to suspect the “Brothers” and follows her intuition about the culprits. Eventually the police believe her and a murdered wife receives justice.

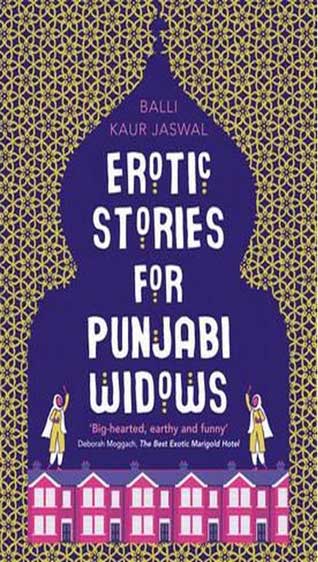

Even the cover works with the physical setting consistent with the scene. A lacy frame surrounds a temple silhouette in a design that can be tatted or crocheted easily, one motif at a time. The design ultimately adds up to a veil, one metaphorically pulled aside by illiterate, emotionally deprived but brave migrants far from their homeland, thanks to the literary gifts of Balli Kaur Jaswal.

[Courtesy: The Buffalo News]

March 18, 2017