Sports

Wrestler Jaskanwar Singh Gill,

aka Jassa Patti

Is A Phenomenon

VINAY SIWACH, DAKSH PANWAR

“Jassa mitti ka sher hai.”

Over the course of the last four years that Jaskanwar Singh Gill alias ‘Jassa Patti’, the heavyweight from Punjab’s Tarn Taran district, has become India’s unofficial No. 1 dangal wrestler, all manners of sobriquets have been used to describe him - from ‘Modern day Dara Singh’ to ‘Virat Kohli of Mud Wrestling’. But few, if any, encapsulate the phenomenon as well as “Mitti Ka Sher”.

This was the description used by a fan on Facebook after Patti lost at the Senior National Wrestling Championship in Indore last year, his umpteenth failure to make the transition from the mud to the mat. It can be translated as both “a lion of mud akharas” as well as “a clay lion” - one a compliment, the other a pejorative. And, depending upon which surface, natural or synthetic, you deem more important, both fit Patti to a T. There is love and respect for him on the former, indignation and scorn on the latter. In fact, the perceptions of him in these two worlds are so radically different that ‘Jaskanwar Singh Gill’, his name on the mat, and ‘Jassa Patti’, as he is known in the dangal circuit, might as well be two different people.

It was this gap that was at play, this time on a world stage, when, on July 28, 2018, the 25-year-old Sikh wrestler exited his first international tournament after the referee demanded that he remove his patka (under-turban) if he wanted to take the mat. Patti said no.

Considerable outrage has followed that incident in Istanbul, Turkey, which happened right before Patti’s first bout at the tournament. His rival got a walkover and he returned home by the next flight. The news has spread from Sangrur to Satara and Bathinda to Brampton - from wrestling hubs to the Canadian city where Sikh-Canadians keenly follow Patti’s career.

Patti finds all this unsolicited attention rather vexing. “I am getting fed up with all these calls,” he says sitting in his living room in Tarn Taran, surrounded by the maces he has won. “Reporters come and keep asking the same questions. Where were they when I was wrestling in dangals and winning?”

Part of the frustration stems from the fact that Patti had to forego many lucrative dangals to attend mat-wrestling camps - even self-financing his month-long stay in Turkey for training before Istanbul’s Yasar Dogu International Wrestling Tournament, in a bid to jump-start his amateur freestyle career.

“I missed out on prize money of at least Rs 170,000 as I brought down my dangal participation to the odd appearance here and there over the last three-four months so as to prepare for mat wrestling,” say Patti.

Last year, he earned around Rs 10 million from dangal, taking together the cash and other things he received as prize, including tractors, Maruti Alto cars, Royal Enfield motorcycles and milch buffaloes.

For an overwhelmingly rural sport with zero corporate sponsorship, these are eye-popping numbers, including for Patti, whose only regular income is as a Constable with Punjab Police. The graduate from Guru Nanak University, Amritsar, got the job in 2016 after winning the All-India Inter-University medal - his only significant title win on the mat so far.

Besides the money, there is the adulation showered on top dangal wrestlers - something that borders on the reverential for someone like Patti. Poems and songs have been written glorifying his achievements. In one, a fan chides his beloved for liking a “cute”, urbane Virat Kohli and proudly contrasts it with his own “pendu (rustic)” choice, Jassa Patti.

The song goes: “… Motorcyle o nit jit-da aa, jit-haar te rabb de bas kude; tere Birat ji Kohli ne kade jhotti jit-ti tan das kude (Virat Kohli might have won a motorcycle, but has he, like Jassa, ever won a buffalo)?”

This fan-following for Patti and his ilk is not merely a counter-culture assertion. There is also a deep religious-spiritual angle to it. The star wrestler, who is remarkably eloquent for a pursuit routinely stereotyped as all brawn and no brain, explains that villagers have traditionally seen wrestlers as spiritual conduits.

“Our lives are similar to those of sadhu-sants of old: they wore langaut (loincloth), so do we. They ate simple food, so do we. There was discipline, physical and moral. In fact, people would say that once a sadhu enters a room, no one knows what he is doing inside - sleeping or meditating. With a wrestler, you will find out in eight days. If there is no output, it means he was doing nothing. So people revere a wrestler,” says Patti.

To this day, he points out, people bring their children to akharas and apply the arena dirt on their forehead and seek blessings. Patti goes on to talk about his own experience. “If a couple can’t have children, they come to us and ask for ardaas (prayer). I remember a childless couple called me home and sought my blessings. I went because I didn’t want to disrespect them. I had tea there and did an ardaas. I later came to know they were blessed with a child. Now I am not going to claim I have spiritual powers and it was because of me. But that’s what people believe, and you don’t want to hurt their feelings.”

According to him, apart from the fact that wrestlers are similar to ascetics in many ways, there is another reason for people’s faith in them. “Because of their physical and moral strength, people believe wrestlers can bear the burden of others’ misfortune. It’s part of the reason you still remember Gama pehalwan, Mehardin pehelwan, Dara Singh - not the movie-wale, who was a professional wrestler, but Dara Singh Dulchipuria.”

But while their popularity endures, ‘Rustam-e-Hind (Heavyweight Champion of India)’ Mehardin and Dulchipur, who once regaled Jawaharlal Nehru with his wrestling, didn’t quite make a fortune. And folklore has it that the great Gama, the undefeated ‘Rustam-e-Zamana (World Heavyweight Champion)’, died in poverty. Patti, on the other hand, has arrived on the scene at a unique time in dangal wrestling’s history. In contemporary mainstream imagination, dangal may still be an obscure, dying sport, forgotten by TV that has paid attention only to its cousin, mat wrestling - if at all. However, in the past few years, come smartphones and cheap, high-speed Internet, dangal has not felt the need for mainstream to be noticed.

From remote villages across the country, its hardcore fans have now found a common platform to watch and share bouts. When that expanding audience needed a superstar athlete to headline events from Una in Himachal Pradesh to Indore in Madhya Pradesh to Varna in Maharashtra, it found just the right person in Patti. He has decimated almost every opponent he has faced to become arguably the most sought-after dangal wrestler in the country.

“Over the last two-three years, Jassa has become a phenomenon in dangals across the country,” says Kulbir Kainour, a ‘Colour’ commentator (a sports telecast term for commentators who have an exaggerated style and engage crowds, quite like in WWE wrestling). A long-time observer of the mud-wrestling scene, Kainour says, “Jassa has beaten all the top stars at least once, a feat not seen in recent times. And thanks to social media, his renown is spread far and wide.”

Last year, having fought “close to 150 bouts”, Patti stated: “Between August and October, I got barely three-four days off. Such is the demand. Sometimes, you just can’t turn down people. But you have to, because you don’t want to get injured.”

In that, Patti touches upon a real fear. So while there’s enough money in the mud for elite wrestlers to comfortably live off their earnings, and sufficient too for a larger base of tier-2 wrestlers to wet their beaks, that fear - usually just a rough landing away on the dangal mud - lurks in the shadows. Unlike mat wrestlers who have access to federation and government support in such an eventuality, a dangal wrestler is on his own.

Patti has endured such times. “In 2011, just when my career was starting, I fractured my wrist and was out of wrestling for three years. Bahut akelapan lagda si (I felt all alone). There was frustration and uncertainty. I would cry a lot. People say wrestlers are strong men, they don’t cry. They have no idea. I think it’s good to cry.”

The second time injury brought him down was in 2014, “when my graph was going up”. “I dislocated my shoulder after a bad fall. When I was rehabilitating, those very people and Internet forums who would hail me started saying I was finished. It was revealing. Popularity is nothing but hawa - no substance,” says Patti.

At times such as this, the Rs 10 million you may have made means little. At times such as this, the mat beckons, with its softer surface, its official recognition, and its medals, meaning promotion and security.

The transition is not easy, points out Mausam Khatri, one of the very few contemporary wrestlers to have excelled in both the mud and mat. “If you are a dangali, it’s difficult to make it on the mat, but even more so if you keep doing both. You will perhaps give up one to get better at another. To row in these two boats at the same time is twice as hard as preparing for the Olympics.”

In Patti’s case, there’s ego too, not entirely out of line for a figure who is larger than life. “Right now, I am a Constable in Punjab Police,” he says. “I have to salute people whom I thrash in the akhara. I need to make it big on the mat.”

To understand Jaskanwar Singh Gill is to understand Punjab’s wrestling. Despite being a state with a rich tradition of producing international wrestlers, especially in the heavyweight category, it has been outshone by neighbouring Haryana in recent years. Since Kartar Singh, who won gold medals in heavyweight category at the 1978 and 1986 Asian Games and a silver in 1982, not many wrestlers from the state have made a mark at the international level - with the exception of Palwinder Singh Cheema, who won gold at the 2002 Commonwealth Games. This decline has also coincided over the years with politically and socially tumultuous times in Punjab.

Patti’s father Salwinder Singh, a former wrestler who was a contemporary of Kartar, sees a correlation between the two phenomena. “Punjab was the likeliest place in India to find big heavyweights. But 1984 and the government’s wide-spread human rights excesses decimated one generation. Another 10 years passed by as the next generation tried to recover. And before it could, the drugs came,” says Salwinder, an imposing man who was known as Shinda Patti in his wrestling days, and was his son’s first coach.

Jaskanwar was born in 1993, when insurgency was ebbing. But his teenage years were spent in a Punjab in the grip of a drug problem. The boy and the menace also crossed each other’s path.

“I was in Class 9, at DPS Amritsar, when a couple of friends picked me up from my house,” recollects Jaskanwar. “They were all rich guys. They came in a Pajero. And when a Class 9 kid sits in a Pajero, he feels he has arrived. We all went to this other guy’s place to party. Suddenly, this guy, who was many years senior to us, asked me to go fetch an envelope from a chap round the corner. I wanted to impress him. I did as I was told. But I saw the envelope contained chitta (believed to be the most prevalent drug used by addicts in Punjab). I didn’t think of it much, a few of them sniffed it, we went back home. But now I think, and it sends a shiver down my body, what if someone had caught me? Or what if I had decided to experiment and snorted a line? I was this close (to disaster),” he says.

“Generations have been lost. People have either run away to Canada or elsewhere abroad, and those who are here are busy trying to survive. How would you expect wrestling or any sport to flourish? Rahi sahi kasar sarkaar ne poori kar di (The government has done the rest of the damage). Unlike Haryana, they have fewer mats here and far fewer incentives. How would you expect people who have no training on the mat to make the transition smoothly? I am trying, but I know it will take time,” Jaskanwar says.

The mat and mud, he further explains, are very different. According to him, it’s like T20 and Test cricket - you need explosiveness in one to expend all energy in six minutes (the mat), and patience and endurance to last 20-30 minutes in the other (the mud).

For the last four years, Jaskanwar has been participating in the senior nationals without really being in contention for the podium. Last year, having come up short once more, and seeing his bitter rival Rubaljeet Singh Rangi qualify for the Commonwealth Championships, a glum Jaskanwar says that he would take time off the mud and focus purely on the mat.

This year, it was to bridge this distance that Jaskanwar had shifted base from Phagwara in Punjab to Sonipat in March and joined the national camp alongside top mat wrestlers at the Sports Authority of India centre in Bahalgarh. This training led to that maiden chance to participate in the international tournament in Turkey. Till he was asked to choose between his faith and opportunity.

International wrestling rules allow players to wear headgear that doesn’t harm opponents during bouts. But the referee’s insistence that Jaskanwar tie his hair like women competitors, and the Sikh wrestler’s refusal citing religious beliefs, resulted in a walkover for his first-round rival. With the United World Wrestling organisation and the host association in Turkey passing the buck, Indian officials accompanying the squad said their pleas went unheard.

But for Jaskanwar or Patti, there could have been no other choice.

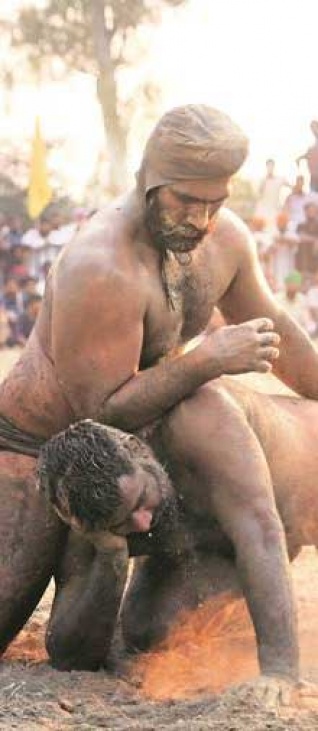

Parna/Patka together are one of the three key ‘Ps’ that make Jaskanwar Singh Gill ‘Jassa Patti’. When he approaches a dangal, he first stands out in the crowd with his yellow parna, tied in the manner of a farmer. Anticipation builds. He first removes the parna and wears a patka, the informal headgear he prefers for wrestling. Next he takes off his exercise pants to reveal monstrous thighs or ‘patt’ - the second ‘P’. Now here is the thing. Unlike mat wrestling where you mostly see sculpted upper bodies, in dangal wrestling it’s the patts that the crowds swoon over. And Jassa possesses the biggest pair of tree-trunks in business today. Then comes the third ‘P’, patkhani, the finishing moves. When he sweeps his opponent off his feet with a ‘dhobi’ (move), and pins him with a ‘kunda’ (another move), the delirious crowd invades the akhara to get as close as possible to the action. Despite the people in the way, you can still see that distinctive patka in a sea of heads and turbans, nodding at people and soaking in the admiration.

Courtesy Patti, the headgear is cool, especially in Punjab. His followers can only aspire to have those patts and patkhani, but they can always tie a parna like him. “A lot of people ask me to teach them how to tie the parna like I do. I feel glad. This is my identity. There were times when I grew sick of my hair because it required so much care. All the dhool and mitti (dust) of the akhara would end up in my hair. It’s one of the reasons you don’t see too many Gursikh wrestlers,” he says, adding, “But I also know that it is because of my hair that I am probably here today. Back in Class 9, when I was hanging out with all those junkies, a part of me wanted the experience. Smoke up, you know… But I didn’t do it because I had kesh, and because I wore a patka and identified as a Sikh.”

So, as much as he wanted to fight that day in July, taking to the mat in Istanbul without that patka wasn’t really a choice.

The disappointment is there, but Jaskanwar has no time to dwell on it. The dangal season has begun and ‘Jassa Patti’ needs to take over.

On the very first day of his return to the mud, from Istanbul, he has two back-to-back bouts, one each in Amritsar and Gurdaspur. The first is a gruelling, 30-minute draw. He has no time to rest or even wash off the slush, before zipping off to the second venue in his sedan, still in his langaut, covered with a chadraa (wraparound). Patti wins that match in 20 minutes, flooring the veteran Joginder from Delhi with a ‘kunda’.

The crowd roars in approval. Jassa Patti is back.

[Courtesy: The India Express. Edited for sikhchic.com]

August 14, 2018

Conversation about this article

1: Hari Singh (Punjab), August 18, 2018, 7:39 AM.

Two quotes in Punjabi will suffice to reiterate this phenomenon, Jaskanwar Singh Gill aka Jassa Patti: "Punjab jinda Guraan de naa te ..." Punjab lives/survives on the legacy of The Sikh Gurus. "Kesh Guru di mohar hun ..." Unshorn hair is the identity given by The Guru, a gateway to The Guru. It is time that we Sikhs stand firmly with him in particular and start a campaign to end discrimination against Sikh sports-persons because of their Sikhi saroop. The Sikh community has already won many battles against discrimination of Saabat Soorat Sikh sports-persons in games like basketball and soccer.

2: Arjan Singh (USA), August 20, 2018, 10:49 PM.

Well said, Hari ji. I agree with you: we as a community need to support Jassa Patti. Maybe the editor can guide us to start a campaign or we should all get together to create one.

3: Hari Singh (Punjab), August 27, 2018, 11:24 AM.

Thank you, Sardar Arjan Singh ji. Sure, as a community we can do a lot once we devote our energies in right directions instead of squabbling over non-issues, wasting energy and time. SGPC, DSGMC, Wrestling Federation of India, all can and should take up the case of Sabat Soorat Sikh wrestlers with the World Wrestling Body. All three bodies will need lots of coaxing to do anything worthwhile in this matter. I feel Sikh organisations in UK, USA and Canada can contribute more positively and forcefully on this issue. The Editor of skhchic.com has played a very commendable role against discrimination of Sikh soccer players with a total positive outcome and victory. Any initiative from sikhchic.com will surely strengthen and support this cause. We as individuals can start a signature campaign petitioning against this discrimination through Change.org and Avaz.org.

4: Brig Nawab Singh Heer - Retd (United States), August 27, 2018, 11:29 PM.

We need to campaign for making such persons role models for our children. We held a session on a at talk show at SSTV. https://www.facebook.com/sursagartvandradio/videos/721594271517601/?t=4