Partition

The Reed Stool

by MANREET KAUR SODHI SOMESHWAR

The following piece is presented to you as part of sikhchic.com's ongoing series, "The Partition & I":

The ruby red seeds of the pomegranate gleamed invitingly as I coaxed my seven-year-old daughter to eat the fruit. Loathe to do any task without being regaled with an accompanying narrative, she asked me to retell the story of how as a child I would steal pomegranates from a neighbor's garden and cause trouble.

Despite several retellings, the story continues to exercise a hold on her, in part because it allows her a peek at the child now obfuscated by her mother's adult facade.

The neighbor's house was across from ours, separated by a narrow brick road into which branches of pomegranate trees spilled from the enclosed garden. In summer, after hours of sweaty play, there was pleasure in crumpling in the verdant shade, gossiping as we ate the plucked fruit. It never occurred to us that the pomegranate didn't belong to us and that, technically, we were stealing.

Before long, the matriarch of the neighbor's house would open the gate, see us sucking the fruit that she had so religiously tended, and let out a howl. Then my mother would be summoned and shown the evidence and the women would proceed to quarrel. My mother would attempt to make amends but the matriarch would dig up old grievances, her voice getting more shrill with each new volley, drawing inquisitive women from other households. My mother, never one to let a jab go unanswered, would argue back, ensuring afternoon entertainment for all.

At some point, the quarrel would run out of steam, and the matriarch would troop back inside, only to return with a reed stool that she would then lean upside down against her front door. It was a symbol that the quarrel would be renewed the following afternoon. Over the next few days this ritual argument would continue, producing minute details from the past; stories were remembered and embellished, grievances were aired and sorrows shared.

This custom of turning the reed stool upside down was a peculiarly Punjabi one, and in the town where I grew up, which straddled the India-Pakistan border, it seemed to hold a particular relevance.

During my childhood in East Punjab (which is now in India, since Partition), West Punjab (now in Pakistan) was omnipresent.

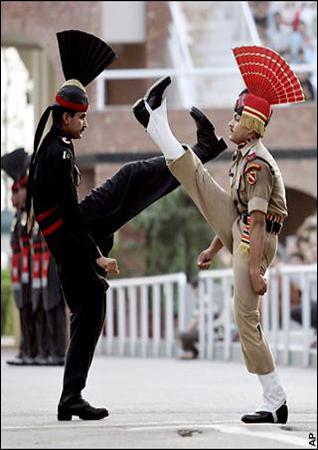

The reception from Pakistan TV out of Lahore was superior, and we consumed a daily diet of Pakistani serials, ghazals and news reports. We naturally chose to disregard the routine anti-India propaganda of PTV. Any visitor to our otherwise-nondescript town was always taken to the border to witness the "Beating the Retreat" ceremony. A colonial legacy, it signaled an end to the day's hostilities as the khaki-clad men of the Indian border security force and Pakistani rangers in olive-green Pathan suits stiff-marched the length of the checkpost, dramatically eyeballed one another, flung the gates open, and, unsmiling, shook hands.

A joint show by the two enemies, it provided a chance to gawk at the Pakistanis on the other side and see that they looked just like us.

Those were the days of respite, when the reed stool was leaning upside down against the border. There were other days when the two countries drew blood. During the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971, my parents trudged through darkness for miles, their young children straddled on their shoulders and clinging to their waists. My family was attempting to flee the border area, which triumphant Pakistani tanks were threatening to breach.

In the 1980s, militants seeking to establish an independent Sikh state rocked East Punjab. The Indian government blamed Pakistan for sponsoring terrorism. Pakistan blamed India for creating Bangladesh and festering the separatist movement in Sindh.

In the 62 years since the partition of the subcontinent, India and Pakistan have fought four wars and regularly accused each other of sponsoring terrorism. In November 2008, Mumbai was attacked by terrorists operating out of Pakistan. Following that, India severed dialogue. After a 15-month hiatus the two neighbors have again initiated talks.

People on both sides of the border are understandably cynical about the on again, off again, sparring. Perhaps it is time to put the reed stool back inside and talk.

[Manreet Sodhi Someshwar is a writer for the South China Morning Post and author of "The Long Walk Home," a fictional look at the 20th-century history of Punjab.]

April 10, 2010

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), April 10, 2010, 11:22 AM.

I am afraid this is going to be an antithesis of 'The Reed Stool' and tad too long despite my best restraint to keep it brief. Fortunately, we did not have any pomegranate or mango trees to separate us from our neighbours. All we had were simple low walls to nominally separate us. We did not need telephones to communicate but to raise your toes about 45 degrees and you were in audio visual contact for as long as you liked. The neighbours became extended families. They were Chacha jis or Taa-ee ji or Chachi, Taa-ee or Maasi, and all children were spoiled with abandon. If you were late, they would enquire 'Hasn't Sangati come back from school yet?' There, now you know my pet name as well! Whatever was cooked was shared, depending on the smell emanating and a hint of suggestion. "What's cooking?" and you had a steel 'kauli' to share. Come Partition, the same relationships were re established with another set of Chachas, Taayyas, Bhaia-jis, Maasi jis, etc. We still participate in their 'dukh sukh' and relationships have withstood the test of time for more than half century ago. These were the lessons that we kids learned effortlessly as a norm of good neighbourly living. Some of the lessons had to be imparted a little violently. Give you one first hand experience. As a kid, I was seriously studying how to play 'gulli dandaa'. Naturally, a well-pared gulli (peg) was essential part to go with a dandaa (rod). We had a small carpentry shop a few doors away, and as a norm they would come to get some 'lassi' on a hot day ... it was freely available then. So, one day, I marched up to the old carpenter and asked him to make me a 'gulli'. He snapped back and said 'Run along!' and that he didn't have time for such a silly request. But I shot back quite stridently that he had the time to get a 'lassi' from our house everyday, didn't he! This must have peeved him for the next day he complained to my parents that their son had give him an 'ulambh'. Now, what the hell was an 'ulambh', I had not the slightest idea. But I did get some thrashing from my father but couldn't understand the reason. I had just stated the facts as they were. My mother gently tried to explain: 'Kaka, you mustn't say like this to anyone." Still, it didn't make any sense to me. No matter, the thrashing was the integral part of growing up and you sometimes got punishment in advance for any possible infraction. Partition brought us to Ludhiana to start anew our lives. We made new friends. One of my closest childhood friends, Jugraj from Lyallpur days, was relocated. It so happened that he got selected for the National Defence Academy in Dehra Dun for his army career. His father, Capt. Satwant Singh, was also a serving officer posted somewhere. They got some agricultural land allotted to them near Machhiwara (Ludhiana) but there was no one to keep an eye from time to time. This was left to me and our other mutual friend, Jaswant Singh Makkar (no relation of the S.G.P.C. fellow). It so happened one day when Jaswant was in Machhiwara village, he missed the last bus. There was no gurdwara or a hotel nearby but luckily a Sardar ji came along and realizing Jaswant's predicament, offered to take him to his home. After settling down, the Sardar ji related a similar incident that happened before the Partition. He was in a village near Sargodha (now in Pakistan) where he was in the similar situation, when an elderly Sardar ji came along and took him home. His name was S. Harnam Singh Makkar. Hearing this, Jaswant perked up and blurted that it was his father and that he had gone to his, Jaswant's, home! What a wonderful story, quite different from the squabbling mothers over a pomegranate. We too had reed stools but to welcome all and sundry to serve as honoured visitors.

2: Jugraj Singh Kahai (Gurgaon, India), April 10, 2010, 7:47 PM.

I agree with Sangat's comments. We were in Lyallpur for some time, and I was fortunate in getting Sangat as a school friend (we lived on the same street). I remember they had a buffalo (1 or 2?) and it used to be Sangat's duty to get the feed for it in the evening. We had to go through the field to get to our destination. On the way, without any hesitation, we used to pluck out 'moolis' and 'gaajars', just wipe them with some leaves, and enjoy eating them. We were never berated for that, although the farmers were not known to us. It seems so unbusinesslike now, but it was expected that travelers along the path may pluck some vegetables. Another favourite was the 'shalgum'. (Of course it, depended on the season.) But sharing was an understood part of Punjabi culture.