History

What Makhan Singh Means to Me

AMARJIT SINGH CHANDAN

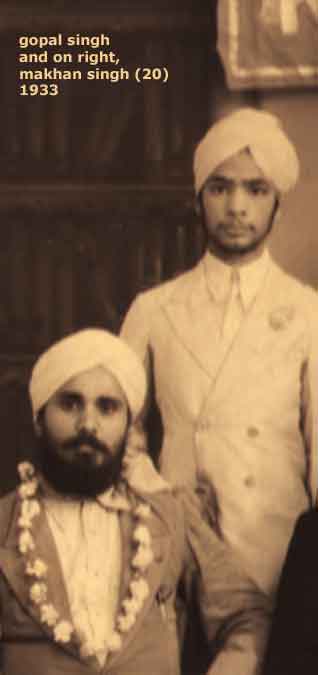

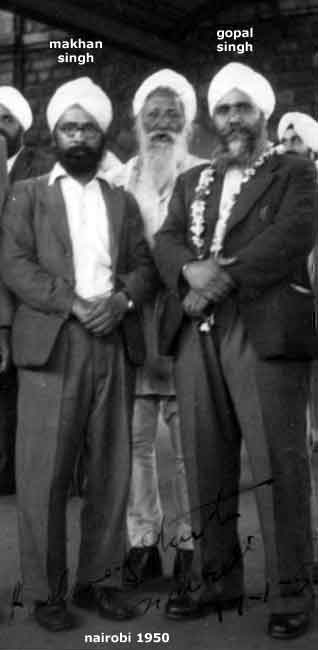

I have a photograph dated January 17, 1950 of my father, Sardar Gopal Singh. He is at the Nairobi Railway Station surrounded by friends who had gathered together to give him a warm send-off.

Father was leaving for the Punjab, his homeland, after many years.

It is quite different from his earlier photos of the early 930s, taken at the same place. Standing next to him is Makhan Singh, his close comrade.

I am in the crowd too, age four, unaware of the goings-on around me. My father is holding my hand.

I vaguely remember the figure of Makhan Singh waving from the window of the departing train and bidding his farewell: ‘Sat Sri Akāl!’

This was to be the last time we saw him. My father and Makhan Singh never met again.

Four months later Makhan Singh was to be arrested and spent almost 12 years in solitary confinement.

My father was to die in the Punjab in 1969, twelve years after leaving Nairobi for good and Makhan Singh four years later in 1973 in Nairobi.

My father always had fond memories of Makhan Singh. His name was repeated in our household time and again, like a chant. He was more than just a family member. After his release from jail, Makhan Singh and dad kept in touch with each other through letters.

I wish they had access to emails and long distance calls then, like we have today. That would have reduced their suffering.

After so many years, I was a bit surprised to read their letters, which I found well-kept in the Makhan Singh Archive in Nairobi University. Makhan Singh even kept copies of his letters he wrote to others.

Both Makhan Singh and my father were the products of mass movements of workers.

I looked up to them as my role models without drawing from their experience. The Maoist movement I joined practised pure individual terrorism in the name of revolution. In prison in my deep solitude, I drew strength from Makhan Singh, amongst others. I truly admired him and still do.

In the end, my father suffered dementia and could speak just two words in Punjabi on his death bed – aa jao – meaning ‘come on in’. I can imagine he must be asking this of his departed loved ones standing on the door step. Surely Makhan Singh was amongst them.

Even in the communist movement, especially in the Punjab, it is hard to find a selfless, self-effacing and principled man like Makhan Singh. He never hankered after power or wealth. He insisted on working in his father’s printing press as a wage earner, not as a proprietor. He never ever had any property of his own. He was a Sikh-Communist in the true sense of the term.

I do not see any contradiction in it.

* * * * *

A NOTE ON POEMS IN PUNJABI BY MAKHAN SINGH

It is a pleasant surprise to read handwritten poems in Punjabi by Makhan Singh.

His public persona, as reflected in and through his political life and writings, has been that of a man who hardly showed his emotions.

All the 50 poems written during 1928-1939 were meant to be recited at gurdwaras and mandirs on religious occasions or dedicated to friends on their weddings or departures from Nairobi to India.

He uses the first line of the Sikh prayer, inscribed in Gurmukhi, as the mast-head -- ik oankar satgur prasad -- “There is but one God. By the Guru’s grace He is obtained” – on the cover of Volume One. (Later he was to become a staunch atheist in the Stalinist mould in the 1940s when he was an activist of the Communist Party of India in Lahore, Punjab).

Two poems are dedicated to his wife, Satwant. One of the poems is on Vithal Bhai Patel and two are on M A Desai on their demise.

The general theme is the reaffirmation of Sikh ideals of humanism, egalitarianism and universal brotherhood versus capitalist exploitation of workers. He is equally critical of the degeneration creeping into the practice of the Sikh faith.

Interestingly, some poems in the second volume share the refrain with those of my father, Gopal Singh Dukhiya alias Chandan, whose poems are now deposited in Desh Bhagat Yadgar Library, Jalandhar, Punjab. Both were also actively involved in the Kaviya Phulwari (literally, ‘Poets’ Garden‘).

It was the norm then to write on an agreed theme with a common refrain trah misra.

Makhan Singh’s poems are well crafted, showing a grasp of metrical composition. Almost all the Punjabi didactic and lyrical poetry written during the national struggle seems to be the collective work or the creation of a single poet.

One of the poems is addressed to my father (whose own nom de plume was ’Dukhiya’) on his departure to India written on August 14, 1933 (Vol 1, p 59). It reads as follows in English translation:

A MESSAGE

O, the son of Mother India, take this message home.

Tell her that I am dying to see her freed from chains.

Go and serve our land, share the sufferings of others.

Keep your mirror [of conscience] clear;

Let it shine and don’t forget us left behind.

O brother ‘Dukhiya’ [literally, sufferer],

your suffering will bring happiness to many.

I wish all the sons of mother India were like you

Who could end all her pain.

Makhan Singh himself went to India in 1940 and returned to Kenya after seven years. That whole decade proved hectic and eventful for him. He was to be detained in 1950 for almost 12 years.

It is worth finding out if he wrote any poems during his stay in the Punjab or during solitary detention in Maralal, Kenya.

July 16, 2013