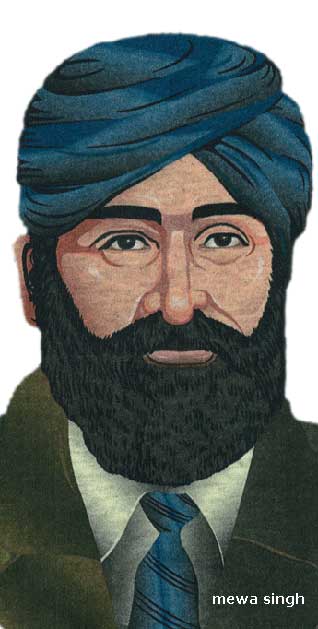

The Mewa Singh funeral procession, 1915. Courtesy: SFU Library Special Collections, Kohaly Collection.

History

Canadian Hero:

Mewa Singh Shaheed

Based on an article by MELANIE HARDBATTLE

“His body was brought to the undertakers, where it was bathed according to the Sikh religious rites and then in a hearse was carried to the B.C.E.R. Depot, where about four or five hundred Sikhs were standing to pray for the soul of the dead. Before the funeral procession started, a photograph was taken and then the procession followed the hearse to the Fraser Mills, BC, singing hymns, notwithstanding the heavy rain.”

– Mitt Singh quoted in The New Advertiser, January 14, 1915

Recently, while looking through one of our collections at Simon Fraser University (SFU) Library’s Special Collections & Rare Books, I came across a photograph that I had never seen before.

I was immediately struck by the stark beauty of the image: the shine of rainy, sepia-coloured streets, nearly deserted, and the charming background of long-demolished buildings and ornate lamp posts, contrasted with the sombre dark clothing of a solemn gathering of SIkh-Canadian men, lined up in orderly rows, arms at their sides, behind a black, horse-drawn carriage.

A small crowd of observers from outside of the Sikh-Canadian community stands to the left, eyes on the group assembled in front of them. Some members of the crowd and their dark umbrellas are blurred and transparent, ghost-like figures; a few individuals are barely materialized, visible by just a glimpse of their feet or a shadowy outline, making the viewer aware of the temporal nature of the photograph and the movement of time. A few curious figures here and there peek out from behind buildings and under awnings.

The whole of the scene is reflected back in shadows by the wet streets.

Curious as to what event it depicted, I turned the photograph over and saw the words “Mewa Singh funeral procession 1915” printed on the back.

Having worked on the SFU Library’s government funded website project, Komagata Maru: Continuing the Journey, documenting the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, I immediately recognized the significance of the image.

This was the procession following the execution of Mewa Singh at the New Westminster, British Columbia jail on the morning of January 11, 1915. Mewa Singh was hanged for the shooting of Canadian Immigration Inspector William Charles Hopkinson in a hallway of the Vancouver Court House on October 21, 1914, a crime to which he freely admitted his guilt.

While I am familiar with the image taken a few hours later of Mewa Singh prepared for cremation at Fraser Mills, and with several photographs documenting Hopkinson’s funeral procession, in the course of my research and survey of academic literature on the subject, I have never come across any images of Mewa Singh’s funeral procession.

The execution-style killing of Hopkinson was the culmination of a mounting animosity between some members of the Sikh-Canadian community in British Columbia and the Immigration tensions that had been brought to a boiling point a few months earlier during an incident involving the passengers of a Japanese vessel named Komagata Maru.

Chartered by a Sikh business man, Gurdit Singh, the ship had arrived in Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet from Hong Kong on May 23, 1914 with 376 passengers, most originating from Punjab. The passengers, all British subjects, were challenging immigration legislation brought into force in 1908. Aimed at curbing Indian immigration to Canada, the Continuous Passage regulation stated that immigrants must “come from the country of their birth, or citizenship, by a continuous journey and on through tickets purchased before leaving the country of their birth, or citizenship.” [This was a carefully calculated racist measure since there were no direct journeys possible then from the subcontinent to North America,]

They were also required to have at least $200 in their possession at the time of arrival. The legislation had a drastic impact on the population originating from the subcontinent in British Columbia, resulting in a decrease of almost 60%, from 6,000 to 2,200, in the two years following its enactment.

With the exception of twenty returning residents, and the ship’s doctor and his family, the passengers were prevented from disembarking by the Canadian authorities. Despite the assistance of a Shore Committee representing the local Sikh-Canadian community and Vancouver lawyer J.E. Bird, the ship and its passengers were kept languishing in the harbour for two months before they were escorted out of the harbour by the Canadian military on July 23, 1914 and forced to sail back to Calcutta. Upon the ship’s arrival in Budge-Budge, (near Calcutta), British soldiers attempted to control the passengers and prevent them from heading back to Punjab -- the British did not want word of their own ignominy to reach Punjab. In the resulting fracas, nineteen passengers were killed by the British troops.

Many of the remaining passengers were either jailed or confined to their villages for several years.

Arriving in Vancouver in 1907, William Hopkinson -- an Anglo-Indian of mixed racial background who had been recruited to serve British interests through spying and subterfuge -- was appointed to the position of Immigration Inspector and Punjabi language interpreter for the Immigration Department in 1909. A prominent figure in the Komagata Maru incident, along with his superior Immigration Agent Malcolm Reid, Hopkinson was also in the employ of the Canadian and British governments as an intelligence agent, monitoring any perceived seditious, anti-British activities amongst the immigrant population in the Pacific Northwest, particularly after the 1913 formation of the Ghadar Party in North America to free India from British rule.

In this regard, Hopkinson employed networks of informants amongst the local community -- [freely using threats and blackmail, since he enjoyed government-granted impunity for his criminal behaviour] -- thus creating frictions within the community.

Following the departure of the Komagata Maru, several murders and assassination attempts occurred in Vancouver and on September 5, 1914, one of Hopkinson’s informants, Bela Singh, entered the Second Avenue gurdwara and shot seven people, killing two. Mewa Singh, a sawmill worker who had immigrated to Canada in 1906, had encountered Hopkinson and Bela Singh the previous June with regard to some legal charges that had been filed against him for smuggling firearms across the Canada-US border. Mewa Singh witnessed the shootings and in his statement at trial he blamed Hopkinson and Reid for “all this trouble and all this shooting.”

At his trial, Mewa Singh declared that he “shot Mr. Hopkinson out of honor and principle to my fellow men, and for my religion. I could not bear to see these troubles going on any longer.”

Hopkinson was commemorated as a hero amongst the citizens of Vancouver and described by the media as “the man who had laid down his life for the maintenance of law and order.” Photographs of his funeral depict the spectacle and very public nature of the event, as thousands of men, women and children lined the streets to pay their respects. His procession, “one of the largest funeral processions ever held in the city,” as described in newspaper reports, consisted of more than 2,000 men, including mounted and other police, members of his military regiment, one hundred firemen, several hundred members of the Orange Lodge, Canadian and U.S. immigration officers and other civil servants. Undercover police infiltrated the crowd to prevent any further disturbances and to protect other suspected targets, such as Malcolm Reid.

Mewa Singh was proclaimed a hero and shaheed by the beleagured Sikh-Canadian community.

But, in sharp contrast, the procession depicted in the Mewa Singh photograph conveys a much different tone. While photographs of Hopkinson’s funeral show the streets so overflowing with spectators that some individuals had to stand atop fences, in this photograph, which I have situated at 8th Avenue and Columbia Street, usually busy streets are remarkably and eerily deserted, save for the small pockets of onlookers. Although newspaper reports estimate the number of men in the procession at between 400 and 500, the photograph suggests that the number was probably a bit lower, between 300 and 400. Consequently, the ceremony appears more humble and, at first glance, much more private and intimate than Hopkinson’s.

However, it was not until the Library’s digitization staff made a high resolution scan of the photograph and I was able to magnify areas of the image on my computer screen that I realized that this was not necessarily the case. Zooming in on the crowd of onlookers to the left of the procession, I was astonished to see the tall, unmistakable moustached figure of Malcolm Reid standing at the front of the crowd, staring straight ahead into the hearse containing the body of Mewa Singh, the man who had murdered his colleague.

Following the Komagata Maru incident and questions regarding his judgement during the affair, Reid was removed from his Immigration Agent position on December 31, 1914. In a letter of December 24, 1914 to the Minister of Justice, Mewa Singh’s attorney E.M.N. Woods’ blamed Reid, “a personal friend” for the troubles resulting in Hopkinson’s death. While stressing that he did not believe Mewa Singh to be justified in his actions, he wrote:

“I have personally strong convictions with regard to the mistakes which I conceive to have been made by Mr. Reid and his associates, and to those mistakes I attribute the unfortunate condition of affairs that exist with regard to the East Indian in Vancouver.”

Following Hopkinson’s execution, officials feared that Reid would be the next target; they proposed to send him east to Ontario for his own safety, but he refused.

Locating Reid in this photograph introduces a whole new dynamic to the image, and an overarching tension that I had not experienced when originally examining it with my eyes alone. The photograph is no longer simply a glimpse into the private ceremony of a grieving community. Reid’s presence, and that of other presumed officials in the crowd, was an intrusion – a trespass – into this privacy. This tension is further developed by the tramlines that dissect the image, much like the conceptual lines that divided Vancouver according to race in the early 20th century.

What were Reid’s motivations for attending this event? I have been unable thus far to locate any official documentation amongst the records of the Immigration Department and M.P. H.H. Stevens digitized for the website that would shed any light on this. Perhaps he was attending in an official capacity, in his new position of Inspector of Agencies in B.C. Perhaps it was a personal mission to see that Hopkinson’s murderer had received what he felt to be due punishment. Or maybe Reid, who had originally been hired by Stevens because of his anti-Asian immigration sympathies, was present front and center as a means of exerting some power and intimidation over the mourners, and to demonstrate that he was not afraid of suspected threats against his life.

His presence, and that of the other officials in the crowd, may have been a warning to the immigrant community that further violence would not be tolerated. Continued investigation into existing records from that period may produce some answers.

However, rather than an experience of intimidation or shame amongst the Sikh-Canadian men in the photograph, it is a sense of pride that is communicated to the viewer. Many of the men in the procession look directly into the lens of the camera, engaging the viewer. Although there is no indication on the print as to who the photographer was, it is apparent that these men are aware of the photographer’s presence.

While members of the crowd are blurred from movement and the majority appear ignorant of the camera, the men in the procession remain very still and pose for the photographer. Additionally, the mention of the photograph by Mitt Singh in The New Advertiser article quoted at the beginning of this piece further suggests that the photographer was likely commissioned by the Sikh-Canadian community to document this moment for posterity.

While previously only images of Hopkinson’s funeral were available as evidence of these events, the photograph of Mewa Singh’s funeral procession allows the Sikh-Canadian community’s story to emerge and sheds more light on the relationship between the two factions. Hidden in a private collection for many years, the photograph can now be digitized and made accessible to the Sikh-Canadian and scholarly communities, and it is almost certain that with their assistance some of the men within this photograph will be identified.

The Mewa Singh photograph is a perfect example of the objective of the Komagata Maru: Continuing the Journey website, which is to make accessible a new perspective of the incident and the Sikh-Canadian experience not present in the ‘official record’ with records from the community itself.

In addition to government documents and other records, the website includes textual records, photographs, books, videos, oral histories and even a diary documenting first hand the experiences of the Sikh-Canadian community in their new homeland. Made possible with funding from the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Canada, under the auspices of the Community Historical Recognition Program, the website also includes biographies of individuals involved in the incident and interactive features such as a timeline and a version of the ship’s passenger list supplemented with information from the community and accounts of events once the ship returned to the subcontinent. As new information continues to surface and is incorporated into the historical record our understanding of this incident becomes more inclusive.

Ultimately this photograph supports the reality that both men were seen as heroes in their respective communities at the time of these events.

Since his death nearly 100 years ago, Mewa Singh has been venerated as a martyr within the Sikh-Canadian community, and is recognized annually. The court house where the murder occurred is currently home to the Vancouver Art Gallery and it is said that Hopkinson’s ghost still roams the hallways to this day.

[Mewa Singh's 'barsi' -- death anniversary -- is celebrated as a grand mela in British Columbia every year. Hopkinson, on the other hand, is unknown to Canadians today, forever lost in the dust-bin of history.]

[Courtesy: History Workshop. Edited for sikhchic.com]

December 23, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Sandeep Singh Brar (Canada), December 23, 2013, 2:17 PM.

So glad that this important part of Sikh-Canadian history has been uncovered. Look at those brave souls in that funeral procession. As hard as the Canadian government of the time tried to break their spirit through denying them the rights afforded to other Canadians and members of the British Commonwealth, ranging from not allowing their wives and children in Punjab to join them, to threats and intimidation to leave Canada - that little band of Sikh pioneers did not give up. And proudly marched on main street in broad daylight, in open and defiant procession behind their martyr.

2: Parmjit Singh (Canada), December 23, 2013, 4:23 PM.

Mewa Singh's statement on why he gave his life for Canada: "My religion does not teach me to bear enmity with anybody, no matter what class, creed or order he belongs to, nor had I any enmity with Hopkinson. I heard that he was oppressing my poor people very much. I made friendship with him through his best Hindu friend to find out the truth of what I heard. On finding out the fact I, being a staunch Sikh, could no longer bear to see the wrong done both to my innocent countrymen and the Dominion of Canada. This is what led me to take Hopkinson's life and sacrifice my own life in order to lay bare the oppression exercised upon my innocent people through his influence in the eyes of the whole world. And I, performing the duty of a true Sikh and remembering the name of God, will proceed towards the scaffold with the same amount of pleasure as the hungry bebe does towards its mother. I shall gladly have the rope put around my neck thinking it to be a rosary of God's name. I am quite sure that God will take me into his blissful arms because I have not done this deed for my personal interest but to the benefit of both my people and the Canadian government." (San Francisco Chronicle, January 12, 1915)

3: Ari Singh (Sofia, Bulgaria), December 24, 2013, 5:34 AM.

Despite the oppression, several hundred thousand Sikhs fought for the British and their allies in their various wars around the globe, and many of them perished! When are we going to learn from the lessons that the Mughals, Afghans and British taught us -- and their current successors are teaching us now?