Fiction

Sharing:

A Short Story

GURDIAL SINGH - Translated from the original Punjabi by NIRUPAMA DUTT

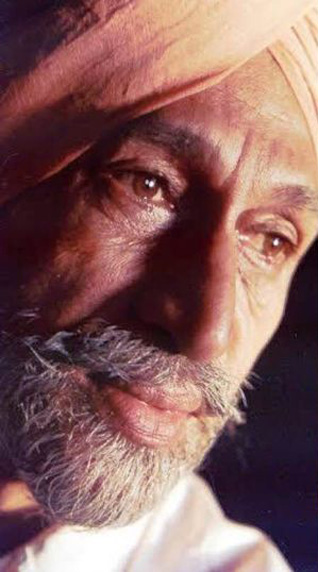

Award winning fiction writer Sardar Gurdial Singh (1933 - 2016) passed away on Tuesday, August 16, 2016.

The woman had just got off the train and was standing at the station looking about her uncertainly. Bantu leaned forward to look at her. His eyesight was weak and he couldn’t quite make out people from afar. When he came closer, he felt that the woman might actually be Jai Kaur.

“Who is there?”

“It’s I, Jai Kaur.”

“How come you are here?” Bantu said this and his face lit up.

Jai Kaur hesitated for a moment and then said, ’I have come from the city. The older daughter-in-law has been admitted in the hospital there.”

“Is all well?”

“Yes, she is going to deliver a baby.”

“Come, let’s walk to the village together.”

Jai Kaur did not know how to react to this invitation. The sun was setting and it would be dark by the time they reached the village. Luckily, no one else had got off here.

Never had the train reached so late. Normally, it arrived well before sunset but today it was running late. She had first thought of staying back for the night at her niece’s home in the town. But she felt like visiting her village and so here she was.

She glanced at Bantu. His eyes were shining and his face looked gentle.

”All right, let’s move on,” Jai Kaur said summoning up courage.

When Bantu took a long stride, the bundle of goods on his head almost slipped off. Holding on to it with both hands, he jumped as though he was trying to control a runaway animal. Then he murmured something and smiled to himself.

“So what else, Jai Kaur?” Bantu asked in an excited tone as they moved on. “Is all well?”

“Yes, by the grace of the Guru all is well.”

“Thanks be to the Lord.”

Then Bantu coughed. He looked around at the soothing sight of the setting sun, pink and orange, spread out on the horizon and felt a deep joy. But seeing the tall shoots of millet shining in the half light, he lowered his gaze again.

The world was still but at times the sparrows hiding in the wild plants would stir on hearing their footsteps and start chirping. When they stopped chirping, it would be still and calm again. For a long distance Bantu walked on, hearing Jai Kaur’s footsteps as she followed him. The sound of her feet seemed to him like the music of the cymbals in the Gurdwara.

“It must be many years since we last met, Jai Kaur?”

“Yes,” Jai Kaur whispered back.

“I think for the past six or seven years you have been living with your younger nephew in Rajasthan,” said Bantu.

“Yes!”

Jai Kaur looked up at Bantu and was quite taken aback at the toll the years had taken on him. He had stopped and was shaking out the sand that had got into his shoes.

His eyes were glowing with the rosy tint of the fading sun. But seeing his white beard, Jai Kaur’s mind came to rest. She no longer felt shy or afraid of Bantu. It was as though she had not realised till this very moment that Bantu had grown so old. When Bantu laughed and moved on she was behind him and could see him closely from head to toe. Bantu’s calves had shrivelled up and looked like dry sticks. The flesh on his neck was sagging. His back was bent, his shoulder blades jutted out like the horns of a calf and his clothes were very dirty.

Just then the other Bantu, from the past, stood before her eyes. Bantu was as handsome as a king. He was tall and well built. He had a broad chest; his eyes glowed like embers and it was difficult to bear their gaze. This was the Bantu she recalled.

Jai Kaur’s heart started beating fast and she anxiously glanced at Bantu. But the next moment a laugh escaped her lips.

“How come you have become so weak?” Jai Kaur asked, her pitying voice breaking the silence between them. “Have you been ill or something?”

Bantu heaved a deep sigh and said, “What do I tell you, Jai Kaur? Things are really bad.”

“Never mind, don’t lose heart so,” Jai Kaur consoled him. “This is the story of every home. It is not easy to take care of the family and make ends meet.”

“That’s true, Jai Kaur, but the times are so bad that no one cares for the other. I am too old to run about doing such chores. Ten years ago I divided the land among my sons. Soon after, they stopped caring for me. My two daughters-in-law are such wretches that they will get what they can out of this old man but not even bother to give him water to bathe or wash his clothes. But then who is one to blame, fate decides our lot.”

Bantu seemed so like a little boy who had been beaten at home and was complaining to a sympathetic ear.

”Never mind, don’t let fate break you so!” Jai Kaur said in a firm voice. “Just look at me. I don’t even have my own home and have to live at the mercy of others. God did not answer my prayers. Now I have to live with my nephews.

“It was different when my brothers were alive. Everyone in this world is unhappy. Hasn’t Guru Nanak said that sorrow is the lot of the world? But what is one to do? We reap what we sow. The quality of the seed decides the richness of the harvest, such is the destiny of life.”

Jai Kaur kept talking and Bantu’s troubled soul found some solace. The only way to overcome sorrow is to share it with others. It was all the more important that he was sharing this with Jai Kaur because the two had a deep understanding between them.

Bantu glanced to the left. The different red hues of the sun had merged in the darkness and a few tiny stars were twinkling in the sky. The breeze had stopped blowing and one could not even hear the rustle of a leaf. The path had become narrow and Jai Kaur followed him unafraid. Jai Kaur’s firm voice, her full body, broad brow, fair complexion and drooping features, which nevertheless had a feminine attraction, were appealing and Bantu wanted to stop and have a good look at her.

“Jai Kaur, this is our field,” Bantu said as he rubbed his feet together and shook the dust from his shoes again, pointing to the standing cotton crop. “We have sown five and a half tons of seed right up to that tahli tree there.”

Jai Kaur stopped at once. Her heart was beating loudly and her breath was heavy. The tahli Bantu was pointing to was the same one which had witnessed an exchange between the two of them thirty or thirty-five years ago. It was under this tree that Bantu had stopped her and held her arm. For a moment Jai Kaur had been scared but then she had felt that Bantu should hold on to her forever!

Recalling that moment Jai Kaur got goose pimples all over her body. Bantu stood still while pretending to clean his shoes and he stared at her with his eyes wide open. Jai Kaur glanced back at him and then lowered her gaze.

She was suddenly afraid of Bantu and found his wrinkled face odious.

“There beyond the tahli is the millet crop,” Bantu said as though he too was recalling his old mischief. “I had asked them to sow cotton there but you would know well that no one listens to the old folks.”

“Never mind, never mind.”

“Jai Kaur, do you know my father was going to sell this tree at the time of my marriage? But I said that nothing doing. I told him that he could pawn the land but I would not let him touch the tahli.”

Jai Kaur felt a wave of sensation pass through her body. Why was Bantu going on about the tahli? When they started walking again Jai Kaur slowed down to distance herself a little from him. Bantu could no longer hear her footsteps. He stopped in his tracks, turned around and glanced back.

“Come along, come along now for we are nearly there,”

Bantu said to her. “Look there’s the village. Now we don’t have to walk much.”

Jai Kaur looked up and saw that the village was indeed not too far away. She took a few quick steps and joined Bantu. “Jai Kaur, ever since your sister-in-law died, I have felt there is no point in my living on thus.”

Hearing him refer to his wife as her sister-in-law and thus indicating that he was like her brother, a laugh escaped Jai Kaur’s lips.

“Well, Jai Kaur!” Bantu said again. “Things do change with time. When we were young, we never remembered God but now one appeals to him to end this existence. But death doesn’t come for the asking.”

“Don’t talk like this. Why are you wishing for death just yet?” Jai Kaur intervened. “Don’t you want to see the weddings of your grandchildren and don’t you want to play with your great-grandchildren? The touch of a great-grandchild ensures deliverance.”

Jai Kaur’s words had a strange impact on Bantu. He wanted to die at one moment and live at another moment.

“You are right in what you say. But what is the point of dragging my feet through life? Everyone in the family is always shooing me away. No one wants to give me two small meals a day.”

Jai Kaur found that Bantu was indeed telling the truth. She felt the same deep understanding that they had discovered together thirty or thirty-five years ago. At that time they were both young and single. They were no longer young but were single even today, living at the mercy of others. For twenty long years she had hoped and prayed that she would have a child but no god or goddess, sage or mendicant, answered her prayers. Her husband’s sudden death ended all hope. For the past seven years, she’d been going for a few days to her husband’s family and then returning again to the doors of her nephews. She had to be subservient to them all for two square meals a day.

“I survive by serving my children and grandchildren. Otherwise they would have cast me away with a cot to the shed in the fields long ago.”

Bantu was still carrying on with his sob story and was sinking into the depths of self-pity once again.

“Jai Kaur, this is no life! And when I die, no one will even remember me. Such is the lot of a lone man.”

Bantu talked on but Jai Kaur was no longer listening.

She was looking at the lit lamps of the village that seemed to her like flames rising from a funeral pyre.

She turned around to look at Bantu. His thin legs were lost in the darkness and his shrivelled-up body was wavering. Jai Kaur felt very sorry for him.

“All right, Bantu, I will take the outer path to the village,” she said and added, “Do not fret so much. Let us laugh away the last few days of our lives. Nothing is going to change now so why crib all the time?”

“That’s true, that’s true!” Bantu said and turned to take the other path to the village.

* * * * *

Translated from Gurdial Singh's original Punjabi short story, ‘Saanjh’ by Nirupama Dutt.

[Courtesy: Scroll. Edited for sikhchic.com]

August 19, 2016

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), September 12, 2016, 2:32 AM.

Another sensitive heartfelt translation. Nirupama ji, I have your 'Stories of the Soil' by the bedside. Keep wielding your pen.