Fiction

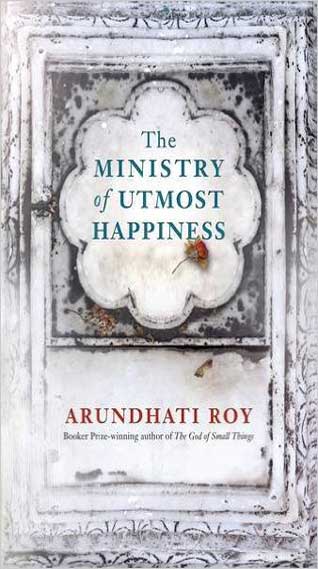

Arundhati Roy Returns to Fiction, in Fury:

‘The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness’

Part II

JOAN ACOCELLA

Continued from yesterday …

In a 2014 interview for the Times Magazine, Roy told the novelist Siddhartha Deb that she was always rather annoyed with the people who, however well meaning, expressed regret that she hadn’t “written anything” since her first novel.

“As if all the non-fiction I’ve written is not writing,” she said.

Suzanna Arundhati Roy, born in 1959 in Shillong, a small town in the subcontinent’s northeast, grew up strong-minded, and had to. Her mother was a Syrian Christian from Kerala; her father was the manager of a tea plantation, and a Hindu and a drunk.

Because of their differing backgrounds, their marriage was frowned on; its ending was even less approved of. When Roy was two, her mother, Mary, took her two children and returned to her family. But, in India, daughters who insist on choosing their own husbands are not necessarily welcomed home when the union doesn’t prosper.

Mary Roy and her children lived on their relatives’ sufferance. Arundhati told Siddhartha Deb that her mother would send her and her brother into town with a basket, and the shopkeepers would put in it whatever they could spare on credit: “Mostly just rice and green chilies.”

The mother was chronically ill, with asthma. Later, she started a school and was busy there. Her children were on their own, and, still bearing the stigma of their parents’ divorce, often found their companions among lower-caste neighbors.

When Roy was sixteen, she left home for good, soon landing in an architectural college in Delhi. Much of the time, she lived in slums, because that was all she could afford. After graduating from college, she hung out with her boyfriend for a while in Goa, where they would make cake and sell it on the beach.

Among the poor, Roy told Deb, she learned to see the world from the point of view of absolute vulnerability: “And that hasn’t left me.”

Indeed, that is what occupied her during the years when, to her fans’ disappointment, she was not writing novels. Journalists are always telling us about the interesting play of contrasts in the “new India”: billionaires walking the same sidewalks as beggars, Bentleys driving down roads alongside oxcarts. Side by side, business and charm, the modern world and the old world.

But, as Roy has argued in the eight books she has brought out since “The God of Small Things,” the two aren’t separate. The new India was built on the backs of the poor.

One of her first targets, in a widely circulated 1998 essay, “The End of Imagination,” was the nuclear tests India carried out that year. To many Indians, these were occasions of pride: their country was a player at last. To Roy, the nuclear program was a sign that the government cared more about displays of power than about the appalling conditions in which most of its billion citizens lived.

Her next subject was the series of dams that the government was constructing in the states of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Again, the project was hailed as part of the new India, and again it was the poor who paid. Farm families were broken by debt, and thrown off their land. (By 2012, a quarter of a million farmers were reported to have committed suicide, and those are only the fatalities that were recorded. A common method was by drinking pesticide.)

After the dams, Roy took on the 2002 Gujarat massacre, in which around a thousand people were killed, most of them Muslims suffering at the hands of Hindu extremists. (India’s current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, who was Gujarat’s Chief Minister at the time, has been criticized for looking the other way as this took place.)

Next, Roy denounced the paramilitary attacks on the tribal peoples of central India, whose land, rich in minerals, the government wanted. (She spent close to three weeks tramping through the forests with Naxalites, Maoist defenders of the tribes, and reported on this in her 2011 book, “Walking with the Comrades.”)

She later denounced the military occupation of Kashmir, where the largely Muslim population is trying to secede from India.

These books -- most of them were collections of previously published essays -- were really all about one subject: modern India’s abuse of its poor. The country’s new middle class, Roy writes, lives “side by side with spirits of the netherworld, the poltergeists . . . of the 800 million who have been impoverished and dispossessed to make way for us. And who survive on less than twenty Indian rupees a day.”

Twenty rupees is thirty cents.

Roy is a good polemicist. She writes simple, strong expository prose. When she needs to, she uses words like “stupid” and “pathetic” -- indeed, “mass murder.” She checks her facts; most of her books conclude with a fat section of endnotes, documenting her claims.

Many people on the right hate her, of course, and not just for her skill in argumentation. There is a Jane Fonda-in-Vietnam element here: although Roy, unlike Fonda, grew up poor, to many she looks like a fortunate person. She may have sold cake on the beach when she was young, but that sounds a little bit like fun.

This problem often comes up when the rich plead on behalf of the poor. The less rich say, Well, why don’t you give your money away? That, of course, is not a solution. And, in fact, Roy has given a lot of money away -- for example, all her prize money. She certainly has no financial difficulties. “The God of Small Things” has sold more than six million copies. But should only the poor be allowed to argue for the poor? If so, the poor would be in much worse trouble than they already are.

In the long second section of the new novel, once Roy leaves Anjum and goes out into the great world you see what she learned in her twenty years of activism. And above all in Kashmir, where most of the latter part of the book takes place, we are shown horror after horror. People bash one another’s skulls in, gouge out one another’s eyes. Bodies are everywhere, hands tied to feet behind their backs, and they are covered with cigarette burns, which means the person was tortured.

In some scenes, Roy kills us quietly. Here is the Indian Army’s “liberation” of the town of Bandipora:

“The villagers said it had begun at 3:30 P.M. the previous day. People were forced out of their homes at gunpoint. They had to leave their houses open, hot tea not yet drunk, books open, homework incomplete, food on the fire, the onions frying, the chopped tomatoes waiting to be added.”

Elsewhere, Roy just lets everything be as appalling as it was. Dogs wander through hospitals, looking for arms and legs severed from diabetics. That’s dinner.

Our new main character is Tilo, the illegitimate child of an Untouchable man and a Syrian Christian woman, who, to cover her sin, consigns her newborn to an orphanage and then goes back and adopts her. Tilo is one of a group of Kashmiri independence fighters. She may or may not have married one of the others, Musa. In any case, she has a steamy night with him on a riverboat. After Musa is gone -- the authorities are after him -- Tilo, too, goes on the run.

She has a baby with her, not hers; it was born in the forest to another resistance fighter. With this baby, she gets into a truck, driven by her friend Saddam Hussain (not that one), with a dead cow in the back. The animal burst from eating too many plastic bags in a garbage dump.

They go to live in a new place, a graveyard where, the story having circled round, Anjum now lives. Anjum has converted the cemetery into a guesthouse, with roofs and walls enclosing the burial plots. The guests lay out their bedding among the graves. Tilo and the baby have a room with a vanity (Lakmé nail polish and lipstick, rollers, etc.) and, under the ground, the body of the woman who was the neighborhood’s longtime midwife.

They are welcomed with a feast -- mutton korma, shammi kebab, watermelon -- which they share with the homeless people who live on the edge of the cemetery, in a nest of bloodied bandages and used needles. They also save food for the police, who will soon come and will beat up everyone if they aren’t given something.

Tilo and the baby settle in. Tilo misses Musa, but “the battered angels in the graveyard that kept watch over their battered charges held open the doors between worlds (illegally, just a crack), so that the souls of the present and the departed could mingle, like guests at the same party.”

Roy’s scenes of violence are hallucinatory, like the chapters on the Bangladeshi independence movement in Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children,” or the union-busting at the banana plantation in García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” She’s often said to have learned from Rushdie, and she may be a little tired of hearing that, because it is to García Márquez (who surely influenced both of them) that she tips her hat, describing post-colonial India as “Macondo madness.”

In fact, all three writers are practicing variant forms of magic realism, which, for each of them, is, among other things, a means of reporting on political horror without inducing tedium. In Roy’s case (Rushdie’s, too, I would say), the effort is not always successful. At times, between the things flying this way and that -- who is this new narrator who is talking to us, telling us that he needs to go to a rehab center? -- you lose your bearings. Roy knows this, and apologizes.

In Kashmir, she writes, “there’s too much blood for good literature.”

Confusion is not the only problem, though. The tone is too even: sarcastic, sarcastic. You feel the need for some large-scale salvation, some great cleansing, which, when it comes, of course can’t really do the job.

In the last scene of the book, Anjum, unable to sleep, goes for a midnight stroll in the city, taking the baby, now a toddler, with her. They wind their way through the people sleeping on the pavement. They pass a naked man with a sprig of barbed wire in his beard. The child says she has to pee, and Anjum puts her down. When the little girl was done, she “lifted her bottom to marvel at the night sky and the stars and the one-thousand-year-old city reflected in the puddle she had made. Anjum gathered her up and kissed her and took her home.”

After the tortures and the beheadings, this is a little too cozy. I expect someone to pop up, any minute, and say, “God bless us, every one!” But maybe, if I’d been to North India recently, I’d be grateful for a little sweetness, if only reflected in a puddle of urine.

The conflict is still going on. Roy’s narrator says that aspiring Hindu politicians in Kashmir have themselves filmed beating up Muslims and then upload the videos onto YouTube.

The Indian government -- the real one, not Roy’s version -- recently banned most social media in order to crack down on dissent. But you can sample videos that pre-date the ban. In one, soldiers beat a man while their colleagues hold him down. Musa says that, in Kashmir, “the living are only dead people, pretending.”

♦

Concluded

Joan Acocella has written for The New Yorker, mostly on books and dance, since 1992, and became the magazine’s dance critic in 1998. She is the author of “Twenty-eight Artists and Two Saints.”

[Courtesy: The New Yorker. Edited for sikhchic.com]

June 2, 2017