Fiction

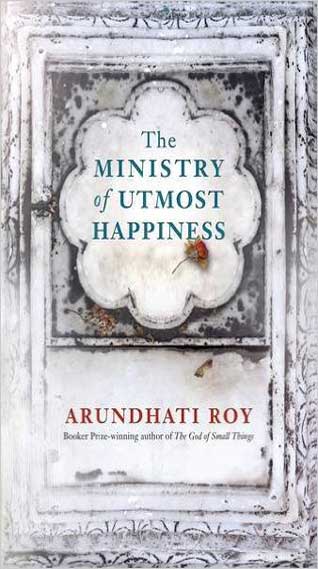

Arundhati Roy Returns to Fiction, in Fury:

‘The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness’

Part I

JOAN ACOCELLA

Arundhati Roy’s “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” (Knopf) is a book that people have been waiting twenty years for.

In the late nineteen-nineties, when Roy was in her thirties, she did some acting and screenwriting -- she had married a filmmaker, Pradip Krishen -- but mostly, she says, she made her living as an aerobics instructor. She had also been working on a novel for five years.

In 1997, she published that book, “The God of Small Things.” Within months, it had sold four hundred thousand copies and won the Booker Prize, which had never before been given to a non-expatriate Indian -- an Indian who actually lived in India -- or to an Indian woman. Roy became the most famous novelist on the subcontinent, and she probably still is, which is a considerable achievement, given that, after “The God of Small Things,” she became so enmeshed in the politics of her homeland that, for the next two decades, she didn’t produce any more fiction.

Now, finally, the second novel has come out, and it is clear that her politics have been part of its gestation. “The God of Small Things” was about one family, primarily in the nineteen-sixties, and though it included some terrible events, its sorrows were private, muffled, personal.

By contrast, “The Ministry of the Utmost Happiness” is about India, the polity, during the past half century or so, and its griefs are national. This does not mean that Roy’s powers are stretched thin, or even that their character has changed. In the new book, as in the earlier one, what is so remarkable is her combinatory genius. Here is the opening of the novel:

At magic hour, when the sun is gone but the light has not, armies of flying foxes unhinge themselves from the Banyan trees in the old graveyard and drift across the city like smoke. When the bats leave, the crows come home. Not all the din of their homecoming fills the silence left by the sparrows that have gone missing, and the old white-backed vultures, custodians of the dead for more than a hundred million years, that have been wiped out. The vultures died of diclofenac poisoning. Diclofenac, cow aspirin, given to cattle as a muscle relaxant, to ease pain and increase the production of milk, works—worked—like nerve gas on white-backed vultures. Each chemically relaxed milk-producing cow or buffalo that died became poisoned vulture bait. As cattle turned into better dairy machines, as the city ate more ice cream, butterscotch-crunch, nutty-buddy and chocolate-chip, as it drank more mango milkshake, vultures’ necks began to droop as though they were tired and simply couldn’t stay awake. Silver beards of saliva dripped from their beaks, and one by one they tumbled off their branches, dead.

This is l’heure bleue, beloved of poets, but now it is filled with bats and crows, like a haunted house. We get ice cream -- butterscotch-crunch, nutty-buddy -- but it is made out of poison. The birds have silver beards, like Santa Claus, but that’s because they’re drooling, in preparation for dying. And what kind of birds are they? Vultures, which live by eating the dead.

This paragraph is a little discourse on industrial pollution, but it is also an act of irony, almost a comedy. At the same time, it is very sad. Once we’ve eaten our ice cream and died, there won’t even be anyone to clean up the spot where we fell. All the vultures will have died before us.

As the book begins, in what appears to be the nineteen-fifties, Jahanara Begum, a Delhi housewife who has waited for six years, through three daughters, to get a boy baby, goes into labor, and soon the midwife tells her that her wish has come true. She has a son. That night is the happiest of her life. In the morning, she unswaddles the baby and explores “his tiny body -- eyes, nose, head, neck, armpits, fingers, toes -- with sated, unhurried delight.

That was when she discovered, nestling underneath his boy-parts, a small, unformed girl-part.” Her heart constricts. She shits down her leg. Her child is a hermaphrodite.

Jahanara thinks that maybe the girl-part will close up, disappear. But month after month, year after year, it remains stubbornly there, and as the boy, Aftab, grows he becomes unmistakably girly: “He could sing Chaiti and Thumri with the accomplishment and poise of a Lucknow courtesan.”

His father discourages the singing. He stays up late telling the child stories of heroic deeds done by men, but, when Aftab hears how Genghis Khan fought a whole army single-handedly to retrieve his beautiful bride from the ruffians who have kidnapped her, all he wants is to be the bride. Sad, alone -- he can’t go to school; the other children tease him -- he stands on the balcony of his family’s house and watches the streets below, until one day he spies a fascinating creature, a tall, slim-hipped woman, wearing bright lipstick, gold sandals, and a shiny green shalwar kameez.

“He rushed down the steep stairs into the street and followed her discreetly while she bought goats’ trotters, hairclips, guavas, and had the strap of her sandals fixed.”

That day, and for many days, he follows her home, to a house with a blue doorway. He finds out that her name is Bombay Silk, and that her house -- called the House of Dreams -- shelters seven others like her: Bulbul, Razia, Heera, Baby, Nimmo, Gudiya, and Mary. All of them were born male, more or less, and all of them want to be women, or feel that they already are. Some have had their genitals surgically altered; others not. They make their living mainly as prostitutes.

Aftab thinks that he will die if he can’t be like them. Finally, by dint of running errands for them, he gains entry into their house. The following year, when he is fifteen, they let him move in. He becomes a full member of the community, and changes his name to Anjum. His father never again speaks to him -- or to her, as we should say now. Her mother sends her a hot meal every day, and the two occasionally meet at the local shrine: Anjum, six feet tall, in a spangled scarf, and tiny Jahanara in a black burqa. “Sometimes they held hands surreptitiously.”

To American readers, no subject could seem more timely. Transgender people and the issues surrounding them are in the news nearly every day. (And this is not the first important novel about a hermaphrodite in recent memory. Jeffrey Eugenides’s “Middlesex,” published in 2002, won the Pulitzer Prize and has sold four million copies in the United States.)

In India, hijras -- people who, though biologically male, feel they are female, and dress and act as women -- constitute a long-recognized subculture. They have certainly been subject to persecution, but they are now edging their way toward acceptance, as a “third sex.” They have the right to vote in India (as of 1994) and Pakistan (2009). In 1998, India’s first hijra M.P., Shabnam (Mausi) Bano, forty years old, took her seat in the state assembly of Madhya Pradesh.

That is what they are legally. As for how they function poetically in “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,” Indian storytelling, from the Mahabharata onward, has tended to favor fantasy, transformation, high color. Hijras contribute to this tradition. People who are defending their right to be women, not men, do not, as a rule, wear pin-striped suits. They wear golden sandals and green-satin shalwars.

In Roy’s House of Dreams, they also paint their nails and sing songs from Bollywood movies. They are fancy; they are fun. At the same time, they are the book’s ruling metaphor for sorrow.

“Do you know why God made hijras?” Anjum’s housemate Nimmo asks her one day. “It was an experiment. He decided to create something, a living creature that is incapable of happiness. So he made us.” Think about it, she says. What are the things regular people get upset about? “Price-rise, children’s school-admissions, husbands’ beatings, wives’ cheatings, Hindu-Muslim riots, Indo-Pak war -- outside things that settle down eventually. But for us the price-rise and school-admissions and beating-husbands and cheating-wives are all inside us. The riot is inside us. Indo-Pak is inside us. It will never settle down. It can’t.”

Anjum will not contradict Nimmo, her elder, but in time she finds out for herself. On her eighteenth birthday, a big party is held in the House of Dreams. Hijras come from all over the city. For the occasion, Anjum buys a red “disco” sari with a backless top:

That night she dreamed she was a new bride on her wedding night. She awoke distressed to find that her sexual pleasure had expressed itself into her beautiful garment like a man’s. It wasn’t the first time this had happened, but for some reason, perhaps because of the sari, the humiliation she felt had never been so intense. She sat in the courtyard and howled like a wolf, hitting herself on her head and between her legs, screaming with self-inflicted pain.

One of her housemates gives her a tranquillizer and puts her to bed.

That is the last orgasm of her life. She has genital surgery, but her new vagina never works right. Sex is the least of her problems, though. Nimmo had said that for most people Hindu-Muslim riots and the Indo-Pakistani war were outside matters, things that happened in the world, whereas for hijras conflict was an internal condition, and ceaseless.

Accordingly, what the hijras in this novel represent, more than anything else, is India itself. With Partition, in 1947, Roy writes, “God’s carotid burst open on the new border between India and Pakistan and a million people died of hatred. Neighbors turned on each other as though they’d never known each other, never been to each other’s weddings, never sung each other’s songs.”

The consequences of that terrible event form the main story of “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.”

But this is not a tale that can be told by Anjum. Although she’s a perfect emblem of India’s predicament, she is too vulnerable, too marginal, to take Roy’s story where it needs to go. I think Roy may have been reluctant to see that. She stays with Anjum too long, and allows the hijra’s story to devolve into anecdotes. Some are wonderful, but they pile up, and they all carry much the same package of emotions: sweetness and recoil, irony and pathos.

Finally, however, Roy takes a deep breath and changes her main character. Just as she started the book with the birth of Anjum, she now stages another nativity. “Miles away, in a troubled forest, a baby waited to be born . . .” The first part of the novel ends with those words.

Continued tomorrow …

[Courtesy: The New Yorker]

June 1, 2017