Books

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil:

His Misery and His Manuscript

A Book Review by B.N. GOSWAMY

This book is sikhchic.com's Book of The Month selection for January 2012

UMRAO SINGH SHER-GIL: HIS MISERY AND HIS MANUSCRIPT, by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Vivan Sundaram & Deepak Ananth. Photoink, India, 2008, pp 253, hardover. ISBN: 8190391119, 9788190391115.

INTRODUCTION

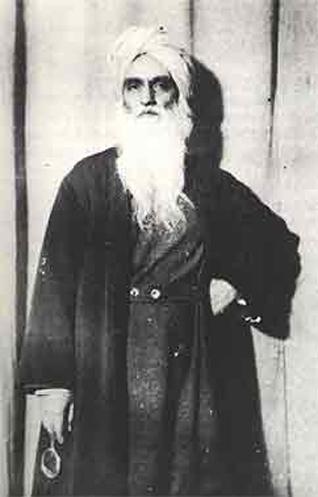

Born in 1870 to the landed aristocracy of the Punjab, Sardar Umrao Singh Sher-Gil of Majitha opted for a more contemplative life than his class had destined for him.

He was a Sanskrit and Persian scholar and interested in the philosophy of religion. He had a long-standing friendship with the poet Mohammed Iqbal and greatly admired Leo Tolstoy, the Russian humanist.

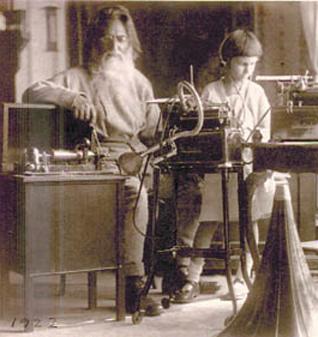

He was fascinated by astronomy, loved carpentry and calligraphy, practised yoga exercises, and had an abiding passion for photography.

Umrao Singh's political sympathies lay with the anti-colonial freedom movement in India. With the discovery by British intelligence of his links with the revolutionary Gaddar Party, however, he was debarred from active politics and most of his lands were confiscated.

He went on to fashion a universe around his scholarly inclinations and the felicities of family life - and his camera was there to record it.

A large part of this record is made up of self-portraits, which reveal a highly self-conscious auteur-photographer imaging his body, his subjectivity and his melancholy. The remarkable photographs that Umrao Singh took over sixty years, beginning 1889, include autochromes (almost unknown in India then) and stereographic photographs.

It was after he married (for a second time) Marie Antoinette Gottesmann-Baktay, a Hungarian opera singer, in 1912, that the family album began to assume the proportions of an archive. The couple left Lahore for Budapest soon after their marriage, and their daughters, Amrita and Indira, were born there. World War I forced them to stay on in Hungary till 1921, when they returned to India and set up home in Simla.

By then photography had become second nature to Umrao Singh. He was curious about the latest inventions and consulted manuals; yet, strangely, there is little mention of photography in his letters and documents.

The Sher-Gils left for Europe again in 1929 as Marie Antoinette wanted her daughters to train in the arts in Paris; they returned to India for good in 1934. Umrao Singh died in 1954. His photographic archive constitutes a legacy that highlights the role of personal agency in the construction of a modern subject.

The hundreds of photographs he took form an extraordinary record of the life-world of a Sikh-European family, and are a valuable document in the archives of modernity. He deserves to be seen as a pioneering figure of photography.

PICTURING THE SELF

A Book Review by B.N. Goswamy

All photos are accurate. None of them is the truth. [Richard Avedon]

I paint

self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I

know best. [Frida Kahlo]

One knows far less about Umrao Singh than about his famous daughter, Amrita.

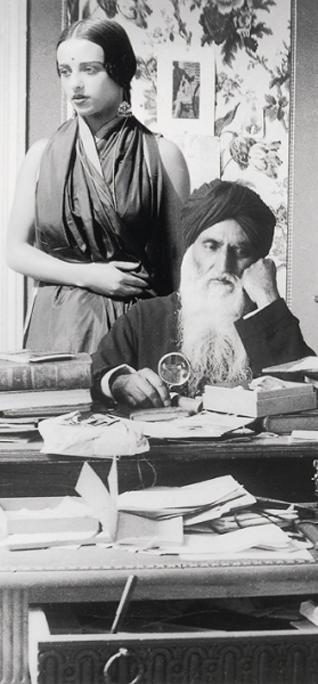

This, to be sure, is understandable, for Amrita Sher-gil is by now an icon whose life was as colourful as her painting, and around whom a whole industry of writing and publication has steadily grown.

But the more one gets to know about Umrao Singh - ‘Sardar Umrao Singh Majithia’ as he might have been known in his growing up years, for he came from the aristocratic Majitha clan - the more one begins to see where Amrita might have got some of her traits from.

Father and daughter chose two different mediums - Umrao Singh was into photography while Amrita, as everyone knows, was a painter - but both of them were almost obsessive in their pursuits, and both of them were happy gazing at themselves.

Clearly, Amrita looked at the world around herself with a keen eye; so did her father, even if concentrated mostly upon his own family. But again and again they seem to return to themselves as subjects, apparently delighting in what they saw.

While Amrita’s self-portraits have been widely published, and admired, Umrao Singh’s studies of himself have had remarkably little circulation. This unusual man, a bit eccentric perhaps - twice married, but more durably to a lovely Hungarian; a scholar of Persian and Sanskrit; somewhat reclusive by temperament but also a devoted family man - developed a passion for that newly-arrived magical device, the camera, early in life.

There is an early study of his own, regally dressed in an embroidered Kashmiri robe, reading, that he took as early as 1892, when he had just entered his twenties. But he seemed to know where he was going, for there are indications that he started documenting nearly everything, most of all his photographs, very meticulously from the very beginning.

This particular study, one of the many that make up a fine new publication - Umrao Singh Sher-gil: His Misery and His Manuscript, it is titled - carries a note in English in his own hand: "Study in a Vase", the caption reads along with a date: "9th of February, 1892", followed by a complete description:

"Umrao Singh: Photo by flash light, Bromide Print. By self. Lahore".

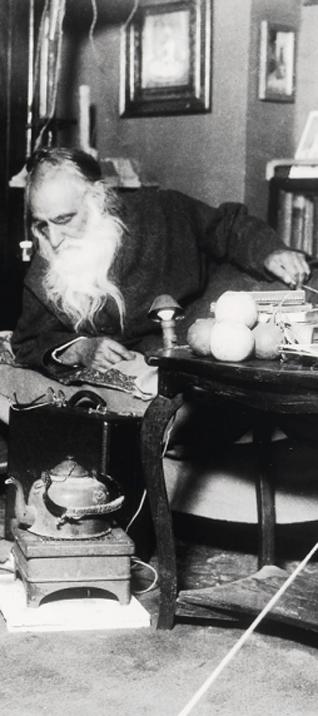

So does a much, much later self-portrait, in which one sees him - or he sees himself, one should perhaps say - as a troubled thinker with a flowing beard gazing straight into the lens, a book resting prominently in his lap.

The caption? Inscribed on the reverse of the photograph in his own hand:

"His Misery and His Manuscript. 14 Nov, 1946. By USG".

More than 50 years separate these two photographs, and yet so much is common between them: the self-awareness, the desire not only to see but also to project himself, and the decision to document things with clarity.

In his life with the camera, Umrao Singh took several hundreds of photographs. The archive of his surviving photographs alone comprises 1536 vintage prints, 308 glass plate negatives, 245 film negatives and 16 autochromes. The man was evidently in love with the medium.

Through his eyes, and that of his camera, one sees, fascinated, Umrao Singh again and again. Now he is a young man in the company of friends and relatives, now he stands alone, bare-bodied except for a brief kacchera, raised hands holding up dark long hair behind his head like a halo.

At one time, he is a Tolstoy-like figure, head resting on hand, immersed in thought; at another he stands posing like some Shakespearean actor waiting in the wings to make an entry on to the stage.

In one photograph, he sits looking like a mad scientist surrounded by all kinds of machines and gadgets with one of which he is fiddling; in another he is seen with his grandchild, Vivan, in his lap, box camera in hand.

Certainly, the family remains in focus: tender, admiring studies of his two daughters, Amrita and Indira; his wife, Marie Antoinette, lounging or regarding herself in a mirror in a rich if oppressively crowded interior; the two girls standing on a rock in the Danube, performing a theatrical piece.

But Umrao Singh keeps returning to himself at the drop of a hat, so to speak, or at the removing of a lens-cap, should one say?

Among the most startling of his studies of himself are those at the age of 50, standing bare-bodied once again, and striking different poses: now like an angry sage about to curse some hapless victim of his wrath, now standing erect as if to take in a full measure of himself in a life-size mirror.

To this very ‘series’ belongs another bare-bodied portrait of himself that has a long, and telling, note scribbled on the mount. The photograph was taken, we learn, on the 11th of August 1930. But we also learn, through the note, that this is a

"Photo taken on the 15th day of fast with reduced weight and belly which has still enough fat for another week’s fast, at least. The legs have always less fat in my case owing to walking exercise but through lack of the exercise often upper body, including upper arms, there was much more adipose deposit which still remains to some extent. It is a pity no photo was taken before fast to show the disproportionate accumulations."

Umrao Singh, in love with his body, was keeping close track.

Much can be done with old photographs. Vivan Sundaram, if I recall correctly, brought in, some time back, magical effects in old photographs using digital intervention. But the photographs in this volume are all seen in their pristine condition, old mounts and all, untouched, exactly as Umrao Singh left them, or meant them to be seen. There may be no true greatness in these photographs, but there is great honesty.

Again, the suggestion that Umrao Singh "deserves to be seen as a pioneering figure of Indian photography" may not be easy to support (for one knows many others), but that it would not be easy to ignore him is certainly true. And there would not be many whom one can designate as chroniclers with a camera, in the manner that he was.

To go back to self-portraits. An Urdu poet once said: Ahl-e hunar koi nahin/ is liye khud-pasand hoon. 'There are none around that are endowed with gifts; that (perhaps) is why I like myself.'

Come to think of it, Umrao Singh could have written these lines.

[Courtesy: Photoink & Tribune. Edited for sikhchic.com]

January 1, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Gurinder Singh (Stockton, California, U.S.A.), January 01, 2012, 9:21 AM.

The Sardars of Majitha were kinsmen of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Sardar Umrao Singh was one of them. Princess Bamba, the last surviving daughter of Maharaja Duleep Singh, wanted to marry a Sikh and Sardar Umrao singh was her choice. But Umrao Singh had already fallen for his Hungarian beau who was well known to Princess Bamba.

2: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), January 01, 2012, 12:54 PM.

Great insight into the artistic life of a great Sardar.

3: Manjeet Shergill (Singapore), January 02, 2012, 8:28 AM.

Now more proud to say I descend from the Majithia family of Amritsar. Those of us who are in Singapore are a lively bunch. I am also a big fan of Amrita Shergill - and her genius for painting and writing.

4: Aman Sidhu (Folsom, California, USA), June 24, 2012, 1:47 AM.

So sorry to know that this great man, a father, a mentor and a guide to a great painter has been forgotten in his own state (Punjab) and community. No doubt he is one of a kind who can be credited with recording our history in photographs at the turn of eighteenth century.

5: baldev singh mann (Surrey b.c canada), January 06, 2013, 1:17 PM.

I am a fan of Amrita Shergill. I am proud to say she came from Amritsar, Punjab.

6: C.S. (New York, USA), August 29, 2013, 10:03 PM.

I am intrigued by all aspects of Sikh history (social and religious). I am also fascinated by humanity, the relationships that people have with one another and the internal conflicts which drive life. I recently learned about Amrita and Sardar Umrao Singh Shergill. While my knowledge of both is limited, it appears that both are artists whose best muse was the "self". It also seems that Amrita chose to view the self in light of palpable physical variables, while her father chose to view the self in light of intangible spiritual variables. In life and in art, both seem to be a juxtaposition of one another.