Books

The Autobiography Of A Sikh-Canadian:

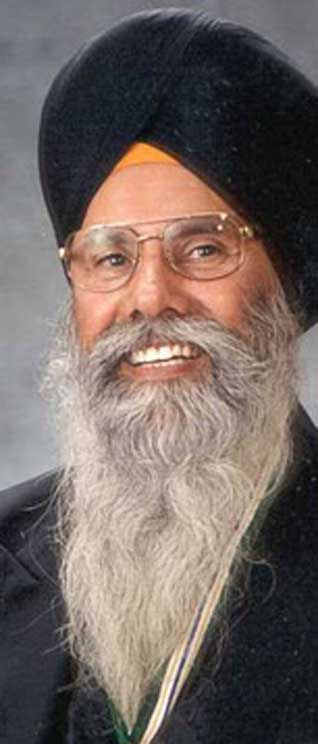

Gian Singh Sandhu

A Book Review by JIM COYLE

AN UNCOMMON ROAD: HOW CANADIAN SIKHS STRUGGLED OUT OF THE FRINGES AND INTO THE MAINSTREAM, by Gian Singh Sandhu. Echo Storytelling, Canada, 2018. English, hardcover, pp 248. ISBN-10: 1987900162, ISBN-13: 978-1987900163

Gian Singh Sandhu recalls the day with a shudder of bone-chilling clarity. He was 27, newly arrived in Canada from Punjab, landing with his wife and three children in his new home of Williams Lake, British Columbia.

It was just before Christmas 1970. Snow was knee-deep. It was -30 C. For the five newcomers, Gian Singh said in an interview this week, the country was white in more ways than one. It “was like another planet.”

Which is not so very different, he laughs, than how 1970s Canada regarded Sikhs, resented by some — as were many people of brown skin — as “Pakis,” their turbans and beards a magnet for attacks and hisses to “go home.”

It all sounds to modern ears as outmoded as it is appalling.

After all, Canadians today are accustomed to ads for Hockey Night in Canada in Punjabi. This is a country with more Sikh ministers in its federal cabinet than India, where Punjabi is the fourth most spoken language, where Jagmeet Singh was elected last year to lead the federal NDP.

In Whitehorse, a clip showing local man Gurdeep Singh Pandher teaching Mayor Dan Curtis (who’d donned a turban for the occasion) some Bhangra dance moves went viral last year. And in Toronto, turbaned Nav Singh Bhatia is the No. 1 superfan of the NBA Raptors.

Still, reaching that status took time for members of one of the world’s youngest (five and a half centuries old) and fifth largest religion.

And Gian Singh, now 74 and living with his wife Surinder Kaur in Surrey, British Columbia, is an engaging guide in chronicling the journey in his book “An Uncommon Road: How Canadian Sikhs Struggled Out of the Fringes and into the Mainstream“, to be released this spring.

The book is the tale of an immigrant’s arrival in a strange new world, of hostility and insult particularly in British Columbia, of persistence through ups, downs and heartaches, and, finally, of security and finding a place to call home.

In that sense, it is as a story as Canadian as, oh, chaat, dal and paneer.

For Sikhs in Canada, now numbering anywhere between 500,000 and a million, the largest pockets in Ontario and BC, “it’s been quite a challenging history, no question about it,” Gian Singh said.

One of the first Sikh settlers in Canada is said to be Capt. Kesur Singh in 1897. In the early 1900s, Sikhs began arriving in British Columbia, working in logging, lumber mills and farming. At first, only men were allowed, to ensure they ultimately left the country. Politicians said openly and proudly that they believed Canada to be “a white country.”

“My God, those early folks really fought the challenges,” Gian Singh said. “They must have had determination that an average person cannot even imagine.”

In 1914, the Japanese steamer Komagata Maru was turned back from Vancouver along with almost 400 prospective immigrants, most of them Sikhs, on board. (Prime Minister Justin Trudeau formally apologized in the House of Commons in 2016 to Sikh-Canadians for that outrage, a measure Gian Singh said “was huge within the community.”)

For much of the 20th century, Sikhs, a small and visible minority, endured the racism endemic in this society. Progress came in small steps. Then, in the late 1960s, the federal Liberal government opened the doors to diversity with changes in immigration regulations.

For that, former prime minister Pierre Trudeau remains, for generations of Canadians like Gian Singh, the man who made it happen. And as it happens, Gian Singh met Trudeau before he was in Canada a year.

It was during a visit by the Queen to Williams Lake on the royal tour of 1971.

“I was new to the country, and here comes the prime minister’s entourage and he stops the car on seeing my turban, and those of a few others standing beside me. You wouldn’t believe it! He stops the car, gets out of the car, walks over to me and said: “Sat Sri Akal (a Sikh greeting).

“And I thought, Wow!”

For Gian Singh, the most difficult challenges for Sikhs came, globally, after the Indian army’s attack on the Golden Temple, the Sikh holiest of holies, in 1984 and the genocide of Sikhs across India beginning a few months thereafter, and the fury and rifts it caused in the diaspora.

He was at the heart of a rupture in Williams Lake within the community and allegations of agents provocateurs from India and the resulting conflicts in gurdwaras.

As something of a born-again Sikh, baptized and taking up the visible articles of faith in his late 30s, Gian Singh’s support for the resistance movement in India -- an independent Khalistan, not dissimilar to the Jewish dream of the ’promised land’ -- as president of the World Sikh Organization of Canada even got him blacklisted from India.

“Our goal was always to speak up for those who couldn’t — or wouldn’t dare, for fear of reprisal and persecution,” he writes in the book. “If their voices were raised in favour of the formation of an independent Sikh nation, it was, and would be, our duty here in the West to aid them.”

For all that, it was after the Air India disaster of 1985, when the bombing of a plane leaving Canada killed 329 people, many of them Sikh-Canadians, that times were most difficult, Gian Singh said.

“The Sikh community basically came under a cloud of suspicion, every one of us,” he said. It “pushed us more to the fringes than anything else could have done. Working our way back into the mainstream was a big challenge.”

The consequence of insecurity and threat is often a retreat into insularity. The trouble with that is the community is not able to make itself known.

Gian Singh recalls being told once, across a table, that with his turban and beard he looked like Iran’s late Ayatollah Khomeini.

“I almost fell out of my chair. I said, tell me what I have done wrong?

“He said, ‘You haven’t taught me who you are.”

“That was a question that needed to be answered. So education is what takes a lot of fear of the unknown away.”

Now, when racism arises, it can be handled from a new position of belonging and confidence, he said. Rather than retreating, the question becomes “how do I find a resolution to this, how do I really educate those people?”

Through the 1990s, there were court challenges in Canada for the right to wear the turban in the RCMP and to carry the ceremonial dagger known as a kirpan — two of the five articles of faith worn by observant Sikhs.

Gian Singh, who has visited India after the lifting of the ban against him in 2016, said his book is the story of a “despised other” growing into a political force and becoming a fully incorporated part of the Canada.

In this country, having Hockey Night in Canada broadcast in Punjabi is a powerful symbol of that belonging.

“Seniors who did not understand hockey before when they saw kids watching it, now they are glued to the TV,” he said. “It’s amazing. That’s what I call mainstream.”

Gian Singh remembers what he told an immigration officer who asked why an Indian air force officer would want to come to Canada in the first place.

“My answer was, Canada is a place, from what I have read, that provides opportunities to everyone.”

Now, after a career as a successful lumbering entrepreneur, an active life serving his community and as a member of the Order of British Columbia, he still believes that.

“I am so grateful. I am so indebted. I would say to God, ‘I made the right move at the right time’. This is my home.”

* * * * *

THE BOOK

A riveting, incisive account of some of the most complex politics in modern Canada, from one of the founders of the World Sikh Organization of Canada.

Widely publicized atrocities in the mid-80s against India’s Sikhs came to define Sikh-Canadians as well: the 1984 assault on the Golden Temple by the Indian military; the death of Indira Gandhi at the hands of her own bodyguards; subsequent pogroms that left over 3,000 Sikhs dead in Delhi alone; the widespread anti-Sikh genocide in the decade that followed across the length and breadth of India; and the bombing of Air India Flight 182 one year later. In “An Uncommon Road” Gian Singh traces the evolution of the place of Sikhs in Canada: from Sikhs dealing with the misdirected blame for the Air India bombing; to combating incendiary false news stories; to overcoming rampant mischief by the governments of India and neglect by the government at home.

Sharing never-before-heard stories, Gian Singh offers a remarkable view of some of the most complex modern politics Canadian citizens have ever faced.

But struggle can lead to liberation.

Over three decades, the World Sikh Organization fought for landmark human rights legislation, from the rights of Sikhs in the RCMP to wear turbans, to campaigning on behalf of religious freedoms for others, and championing the acceptance of gay marriage.

‘An Uncommon Road’ is the celebration of an extraordinarily resilient people and a moving roadmap for how individuals, and a community, can fight for their own social justice and - in doing so - gain justice for all.

[Courtesy: The Toronto Star. Edited for sikhchic.com]

January 28, 2018

Conversation about this article

1: Manbir Singh Banwait (Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada ), February 14, 2018, 9:53 PM.

If anyone wants to pre-order this book, it’s available on Amazon. Release date is April 3rd on Amazon.