Books

Am I an Immigrant Writer?

AMIT MAJMUDAR

I learned recently, to my surprise, that I had written a novel about the immigrant experience.

The novel I thought I’d written was simply about a mother and daughter, but the inside flap of the book jacket made it clear I had “written anew the immigrant experience.”

Of course, I do happen to be an Indian-American who wrote about Indian-Americans, so I suppose it made sense to present the book that way. It’s important that the packaging match the contents; no one wants to open up a box labeled 'Rice Krispies' and shake out a bowlful of 'Cocoa Puffs'.

The more I studied the book, as a marketable object, the more I thought about how, for me, being a writer is related to being a son of immigrants and how complicated the situation is.

The conventional wisdom about being a “minority” -- how white-male privilege will cheat you out of your due -- doesn’t really apply to writers. A minority author may well have an advantage.

The American fiction-reading world, though sometimes reproached for not translating enough contemporary literature from foreign languages, actually has a huge appetite for stories about other people who live in other ways. And an abundance of these stories are written by authors who embody the American and the “foreign” at once.

Publishers are a shrewd bunch, if “shrewd” can be applied seriously to people who sink money into the production of books, a seemingly losing endeavor. They know a book’s success has a lot to do with how it is marketed, and they wouldn’t push something as “fiction about immigrants” if that killed readers’ interest.

And yet this label does pose some obstacles. Fiction strives to attain the universal through the particular; readers want to relate to characters, to see themselves.

The burden is on the writer, then, to make his or her experiences and observations resonate across any divide between writer and audience, whether it be gender, religion, race, geography or all of the above. If a reader comes from the same cultural background as the author, those moments of self-recognition that bind someone to a book are, inevitably, more likely to occur. It’s a kind of home-field advantage when your life’s basic details overlap with those of your reader.

That may well be how the art itself favors a majority author who writes for the majority. For a minority writer, the strangeness that attracted a reader’s curiosity in the first place is also a strangeness that must be overcome.

This leads me to reader expectation. Here, particularly for realist fiction, the question is one of authority. Do we judge a white male writer more critically when he writes about a minority? Are we on the lookout for something to seize on as evidence of unwitting racism? William Styron dealt with considerable backlash for voicing a black slave in “The Confessions of Nat Turner.” What if Tom Wolfe were to make the generalizations about Dominicans in America that Junot Díaz makes with such authority and charm?

Notice how many celebrated minority writers of our time -- Mr. Díaz, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jhumpa Lahiri -- tend to write inside their own communities. One explanation may well be the nature of realism, which is (for now) literary fiction’s dominant mode: the artistic need for observed detail, and the tendency of literary novelists to tweak their personal experiences into fiction.

Write what you know, young writers are taught. This may well reinforce, and be reinforced by, our sense of a writer’s being an authority only on his or her own community, his or her own people.

So, in a paradoxical way, the freedom to write about your own experience turns into a restriction on the subject matter permissible to you. Your selling point governs how you are perceived.

You can write, not about a mother and her daughter, but about an Indian-American mother and her Indian-American daughter. If you do what you do “well,” the book’s themes (love, family, mortality) will be lauded for transcending their context. That is, the book’s success will be proportional to the extent its cultural strangeness dissolves in the reading. We call this “universality.”

Readers don’t want the differences to estrange them -- for all their curiosity, they actually want the differences to disappear. They want to recognize themselves.

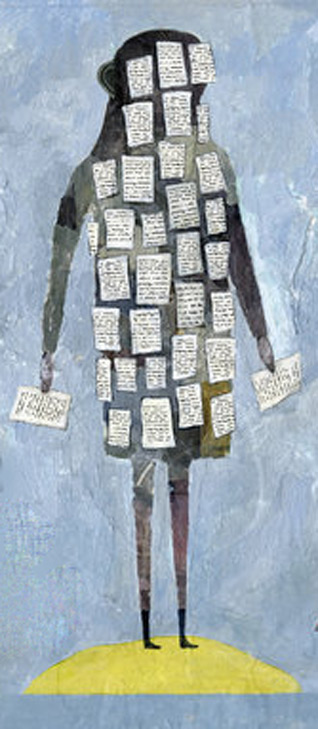

This is all part of the larger paradox of fiction, where the characters must be specific enough to be anyone. In the end, the packaging may simply serve as an introduction. The true meeting takes place when the book opens, and a stranger reads about -- and comprehends -- a stranger.

The author is a poet, novelist and diagnostic nuclear radiologist.

[Courtesy: The New York Times]

May 7, 2013