Sports

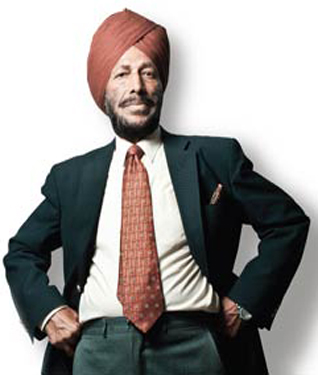

The Milkha Way

by NISHITA JHA

On a breezy summer morning, Chandigarh’s Golf Club is packed with men sizing up the competition. Before the tee-off for the Club’s annual tournament, Digraj Singh of Digraj Golf formally explains the rules of the game.

As gathered golfers banter over the announcement, one man stands quietly to the side - his eyes never leave the cup. Local reporters throng him to solicit quick bytes on everything, from the elections to rampant drug use in Punjab. Milkha Singh quietly requests them to return after the game. As a photographer asks the trophy hopefuls for a group shot, I.S. Bindra, Chief Secretary of the Punjab Cricket Association, booms jovially, “I hate standing in the same frame as this man. He always steals the attention away from me.”

But it’s been a while since the spotlight last shone on Milkha Singh.

The story of the Flying Sikh - the boy who survived the Partition of Punjab to represent India at the Olympics in 1960 - is the stuff of legend. While Chandigarh has grown accustomed to their resident racing hero, for the past few years the real celebrity in Sector 8 has been the athlete’s son - Jeev Milkha Singh, the highest ranked Indian golfer in the world.

Milkha’s vivid racing exploits have faded into sepia tones.

Rakeysh Om Prakash Mehra’s upcoming biopic may render them in technicolour again, but films can often have an even shorter shelf life than the legends they are about.

Bhaag Milkha Bhaag will focus on Milkha Singh’s life from 1946 to 1960. In the run-up to the Olympics, bracketed in these years is arguably India’s most inspirational sporting story of glory.

Even as the focus shifted away from him, Milkha’s own focus hasn’t faltered. Four hours later that day, his name is announced as the winner of the golf tournament. He has already left to fulfil another obligation.

“He is always looking for the next challenge,” laughs journalist and family friend Don Banerjee - “Even when Jeev won the Asia Cup for the first time and we were celebrating his victory, Milkha Singh said, ‘Well done son, now you know how much harder you have to prepare for Europe’.”

Milkha Singh, while not “moving on to his next challenge” and merely on his way to make a public appearance, is often joshed in this tenor. His friends, made over many years, gather around him, swapping old Milkha tales of yore.

Milkha Singh is never embarrassed by this. He often interjects with an extra detail or dialogue. It is not unusual for him to refer to himself in the third person. When a golf buddy teases him about how well the film about “that other athlete” Paan Singh Tomar is doing, Milkha is ready with a retort; he was Tomar’s captain and once defeated him at his own event - long distance running - in spite of being a sprinter. General hilarity ensues.

Milkha Singh doesn’t offer trivia about himself with arrogance, but rather a sense of surprise that everyone doesn’t recall the details. Track records show Milkha as the man who stopped short of bringing an Olympic medal home. At the final moment of that historic race, he looked over his shoulder at Malcolm Spence from South Africa, missing the third place in a photo finish.

“After I won the Gold at the Commonwealth Games in 1958 and began training for the Olympics, the whole world knew I was going to win, but I dropped that medal,” he pauses, and finishes with an oft-repeated line, “It was bad luck. Not just mine, but India’s bad luck.”

On his visits to Chandigarh to prepare the script for BMB, writer Prasoon Joshi was surprised when Milkha Singh handed him a slim, self-authored book, recounting in chronological order the major events of his life. Over the hundreds of hours he spent with Milkha, Joshi remembers that the book became a guide for the topics that he had to steer clear of to get to the story he wanted to tell. “It is almost as if the brand and the man have become one,” says Joshi.

* * * * *

Later in the afternoon, Milkha Singh arranges his lanky frame on a large armchair. The plush house, with its large staff and two identical black Labradors, is always in motion. A nanny chases Milkha’s four-year old grandson Harjai, a man holds a travel itinerary for Jeev Milkha Singh, and the staff ferries trays of food and cold beverages constantly.

Amid this, Milkha Singh is quiet yet affable.

“I did not stay for the award ceremony at the Golf Club because trophies are meaningless. I donated all my medals to the Sports Authority because Milkha Singh doesn’t need them.”

He has this avuncular way of ending his stories with a life-lesson.

“All of these,” he gestures to the gleaming trophies that line the walls, “are Jeev’s.”

It is not that winning the tournament is meaningless. Jeev says that playing golf with his father can be very hard. The senior Singh is extremely competitive - “He only plays to win.”

Perhaps it is the fear of looking over his shoulder, of missing another victory that has him constantly scanning the horizon for his “next challenge”.

There is a persistence and longevity to Milkha Singh’s ambition. B.D. Gandhi, Milkha Singh’s colleague and friend of 20 years, says that being “number one” is an obsession for Milkha, whether it’s at golf, rummy or out-drinking his friends. Even if Milkha cannot risk a sideways glance, he must look back at his past to explain this.

After warnings about the trains full of dead bodies running between India and Pakistan, 17-year-old Milkha was one of the young men who stood guard over his village in Faisalabad, sword in hand. “I was terrified. I had never killed a man,” he says, growing silent, recalling the carnage that followed.

“There were more than a thousand bodies littering the ground. Dogs and hyenas were feeding off my parents and neighbours. The stench of death. You couldn’t escape it for three miles around the village, wherever the wind blew. They took all the young girls. Who knows what happened to them …” the sentence hangs before he gathers himself. “But I know that a few of them are still alive. I get messages saying that they want to meet Milkha Singh.”

Milkha Singh fled to New Delhi, hiding under a seat in the ladies’ compartment of a train. He says he spent days scavenging among the thousands gathered at the station, weeping, wondering what he had done to deserve such a fate. He eventually located his sister who was married into a family in Shahadara. But her in-laws couldn’t stretch their meagre rations to feed another hungry mouth. Milkha tried to return to New Delhi and was thrown in Tihar Jail for travelling without a ticket.

“In jail, I decided that the only way to survive was to become a dacoit (robber), because anything was better than dying of hunger, and most certainly better than living off the scraps people threw at me. At least I would be able to feed myself, and send some money to my sister,” he pauses, “Your generation can never understand what desperation is like.”

Scraping money together for bail, his sister sent Milkha Singh to their brother, a serving officer with the British Army. The brother convinced Milkha to join the forces instead of going rogue. Rejected thrice, his brother finally paid a hefty bribe to get Milkha in.

* * * * *

On his first day in the army, the jawans ran a 5-mile long cross-country race in batches of a hundred. Milkha Singh was sixth in his group. He now believes he developed a technique for running in his village, where he attended a school several miles away.

“My stamina increased because of the sheer distance I travelled, and I developed speed because one had to sprint from one spot with shade to the next.”

He was excused from the duty parade, but the trade-off was a cross-country run every single day. The only change in diet that his army instructor permitted was an additional mug of fresh buffalo milk with an egg in it. Bitter rivals among the ranks attacked Milkha with lathis as he slept to keep him from competing in the trials for National Games. Covered in bruises, running a high fever, Milkha ran anyway, and qualified.

Jeev recalls early golf training, when Milkha frequently repeated there was no point playing unless his hands bled from swinging the club.

As a competing athlete travelling the world, Milkha’s life was a colour-drenched composite that the film now hopes to capture. Straying from his own formula of ending every story with a moral, Milkha Singh speaks with innocent candour of the female attention he received everywhere he went.

“Be my girlfriend, I would tell them. Spend time with me, and then let’s go our own ways.” Muslim women would lift their burqas to marvel at the Flying Sikh.

To move from a life filled with movement and possibility to the slow world of a government job, as the director general of sports in Punjab was a tough transition. B.D. Gandhi, who was Milkha Singh’s assistant from his first day at work to his last, laughingly recalls Milkha groaning, “Even if you do all my work, Gandhi, there will be days when I will have to sit for hours waiting for a meeting. I will have to show up in an office, and I cannot imagine doing that.”

But Pratap Singh Kairon, then the Chief Minister of Punjab, was determined to have Milkha Singh fronting sports in the state.

Being a celebrity in a bureaucratic set-up freed him from some red tape.

“He would ask me to dial the number of any chief minister to set up a sporting camp in their state. All I had to say was Milkha Singh is on the line,” says Gandhi.

Milkha was keen to make structural changes. His army background had drilled in the importance of letting athletes train in isolation, away from distractions. He organised camps in places like Srinagar, where he would run and play with young sportsmen, and deliver his now-trademark inspirational speeches. In the happy position of being able to help, he gave away money or bicycles to those who needed them. His efforts were bolstered, in no small part, by the company he now kept - a close friend of Nehru and his grandson, Rajiv.

It was around this time of settled prosperity that Milkha Singh married Nirmal Kaur, the former captain of the Indian volleyball team. Soon after, life assumed different rhythms - rummy and golf, a jog by Sukhna lake, a visit to the office, and then coming home to play with his children.

When the young Jeev began to play competitive golf, Milkha Singh’s missed Olympic medal began to glint in his sights again.

“I was not half the man I am now. I was not tough until my father became involved with my golf,” says Jeev.

Digraj Singh, Jeev’s childhood friend, remembers when Jeev was playing a tournament in Macau and Milkha was admitted to a hospital with dengue. Digraj rushed to the ward to check on Milkha, and found the 76-year-old pacing around the room critiquing his son’s strokes on the tiny television in the corner.

“There’s never been any option but to be the best, that’s how he brought us up,” says Jeev.

Milkha Singh is vindicated by Jeev’s victories, but second place doesn’t always sit well with a man who won 77 of the 80 races he ever ran. As he shows off Jeev’s various trophies, Milkha’s pride might be tinged with thwarted ambition.

“These days, trophies bring money and endorsements. I had so many more of these, but no money to show for it,” he says.

Faced with fourth place instead of the medal-winning third at the Olympics, Milkha Singh bristles with justifications, many of which are true; his lack of training was responsible for him looking over his shoulder; he equalled the record, but the photo-finish meant he lost the bronze.

“I still dream of the tracks, of the crowds rising to their feet and clapping wildly, those seconds are in my blood,” he says.

What happens when he reaches the finishing line? “I win,” Milkha Singh smiles.

[Courtesy: Tehelka]

April 16, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), April 16, 2012, 8:13 PM.

What an inspiration! All parents should have this 'do or die' attitude in sports and pass this on to their children. Why? Because then they won't have idle time for alcohol, tobacco, drugs, over-eating and general anti-social behaviour!

2: Kanwarjeet Singh (Franklin Park, New Jersey, U.S.A.), April 18, 2012, 7:10 AM.

Every time I read about Milkha Singh I lose sight of my troubles. Generations born after the 1960s do not really understand the meaning of desperation and hard times - as so rightly pointed out by Milkha Singh. Re Baldev Singh ji's comment: so very well stated! We need to get discipline in our lives and our kids' lives.