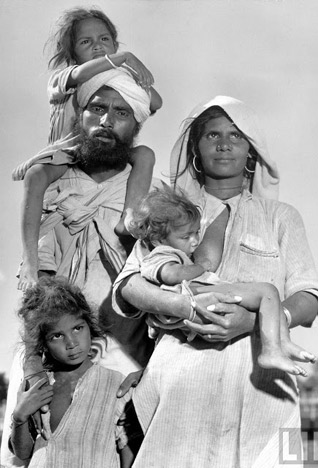

Images: details from photos of the Partition of Punjab by Margaret Bourke-White. Courtesy, LIFE Magazine.

Partition

The Partition of Punjab:

The Story of My Dad

Part III

INNI KAUR

Continued from yesterday … Part III

I find an essay written by Dar ji’s son, Prof. Darshan Singh Maini. I savor each word. Dots connect, a pattern appears. It tells me how Dar ji lived. The title says it all - “Epitome of a Gurmukh”.

Here it is, reproduced.

EPITOME OF A GURMUKH: BHAI MEHTAB SINGH

It is always difficult to talk about one’s father even when one is distanced from him by over half a century. For one’s emotions are so deeply intertwined with that image as to put “the imagination of loving” – to use a Jameson phrase – to an exacting text.

For the distancing, one needs to draw a portrait in order to achieve the right perspective. In a way, I have already waited long enough in terms of time, but in the evening of my own life, stricken and waiting for the call, I find the figure of my father more than a putative fact of life.

In a most compelling way, his life, work and heroic death in the communal ghalughara (holocaust) of 1947 draw my spirit, to bring it closer than ever before, to the Sikh ethos, heritage and world-view. For he had become a living symbol of the Gurmukh ideal well before his brutal killing by an incensed Muslim mob, a vibrant soul in labour -- and action, in word and deed.

And, now, when nostalgia and memories peak up in my days of pain, his image beckons me from afar. The fact that he turns up in my dreams so frequently in so

many forms and aspects only testifies to the nature of my enterprise. The problematics of portraiture, then, become at once a question of rhetoric and metaphysics.

There is only one surviving photograph of Father – Bhai Mehtab Singh, as he was known, in which he’s in his summer dress, a white kurta with the kirpan gaatra (belt) slung across his front, and wearing a spotless white turban. He always used khaadi (homespun fabric), and I recall how, in winter, dressed in a dark brown achkan and chooridars, he was a vibrant presence to be felt.

Soft-spoken, a person of few but telling words, there was an aura of quiet dignity about him.

As far as I know, or remember, he always retired early to bed after the daily recitation of the Rehras Sahib and dinner, and was up in the small hours of the morning to be ready, summer or chilly winter, for ablutions and simran and the session with the Guru Granth in the room upstairs.

Then the daily visit to the main gurdwara on the River Jhelum, a complex of buildings raised during his stewardship of the shrine as its president.

An affluent timber merchant in that timber town, he used the best part of his time, resources and energies in the affairs of the community and the nation. Drawn ineluctably into such historic saakas (events) as the Nankana Sahib tragedy, Jaito-da-morcha, Guru-ka-bagh morcha and the Singh Sabha Movement, he later threw himself, heart and soul, into the freedom struggle, which culminated in his incarceration in the Gujarat Central jail during Gandhi’s Civil Disobedience Movement.

He had succeeded Avtar Narain Gujral (father of former Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral) as President of the Jhelum Congress Committee at the time of his arrest. When he was in jail, I recall our weekly visits to the prison (meant for “A” class political prisoners) which then housed, amongst others, “Frontier Gandhi” Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlu, Dr. Gopi Chand Bhargava, Devadas Gandhi and Master Tara Singh.

I recall – some 70 years later – the scene of his release from the Gujarat Jail under the Irwin-Gandhi Pact, a scene etched in my memory in vivid detail:

It’s an open car decked up ceremoniously, threading through the milling crowds on its triumphal journey over the Jhelum bridge. As the festooned vehicle honks and honks to make way, crowds carrying all kinds of welcome banners and chanting slogans and songs of Inquilab (revolution) to the beat of country-drums and trumpets whip up the moment into a frenzy of sounds, cascading over our garlanded heads.

I watch, wonder-eyed, a boy of 11 years, those spectacular proceedings from the vantage point of my father’s lap on the rear seat amidst a mound of marigolds, and next to me on the seat is Inder Kumar Gujral (later to be India’s Prime Minister) nestling in the lap of his own father, and drinking in the tone of that hour

of grace and glory.

We appeared then to be sitting as it were, across the hump of history.

However, I must return from that nostalgic scene or interlude to father’s strenuous and unsleeping quest for the nirvana embodied in the songs and scripture of his faith. Which brings me back to my childhood days, and to the aura or ambience of a Sikh home.

There was always an air of lightness even during the most vexing days when father’s business suffered huge losses as a consequence of his “Jail Yatra’. For he had steadily honed his life and style in rhythm with the Sikh philosophy of bhana, or a graceful acceptance of the ordained ordeal.

I remember one major and memorable turn his life took when he undertook the crowning project of his life devoted to the ideals and insights of Sikhism. A scene flashes across my mind of the family’s annual journey by train and on horse-back to Sri Choha Sahib, Rohtas, on the occasion of the Vaisakhi festival.

For this historical Sikh shrine some 30 miles away had been an obscure little place housing a small chashma or water spring, associated with the name of Guru Nanak. According to the prevailing legend, the great Guru, during his divine mission in those parts, had struck this spring of clean, fresh water with his stick when the thirsty Mardana was in great torment in that wilderness of stonecrop on a plateau just below the Rohtas Fort, now a crumbling edifice gone to sand and seed for the most part.

Reportedly, Guru Nanak’s celebrated dialogue with Gorakh Nath, the Siddh yogi, was conducted around this part of the sprawling hills. It was then this site which attracted the roving and revering eye of father, and he set about raising not only a beautiful gurdwara and a big blue water pool, but also a complex of resting rooms, a large area, a dispensary and other creature amenities.

As a result of his visionary labor, Sri Choha Sahib became a known place of pilgrimage, and drew thousands of devotees each year. I wonder if after Independence, this shrine has anything of that name which it enjoyed for a brief space of history. I guess, like most such shrines now in Pakistan, it could have in 50 years’ time gone into neglect, or even appropriation. A point, I suggest, for the SGPC to ponder, which reminds me of father’s long and fruitful membership of that apex Sikh body.

For I recall his periodic visits to Amritsar, and the sustained interest in the polity and progress of the community. I’ll come to his newspapers and magazine articles in such journal as Phulwari, Pritam and Fateh some other time when I am in a position to go through files of old magazines in our libraries. But, suffice to say here that his political pieces, theological essays and scriptural explications were all of a piece and constituted a corpus of insightful commentaries.

In 1936, I was taken by father to the Khalsa College, Amritsar, from where I graduated with Honors in English in 1940 before moving to Lahore for the Master’s degree. He wanted his son to be initiated at the premier Sikh institution of higher learning, a thing he considered a matter of pride and prestige, of duty and faith.

The first thing that he did on arrival in Amritsar was to take me to Darbar Sahib for darshan ishnan and blessings. That done, he took me straight to the kothi of Bhai Vir Singh, the great Sikh poet, essayist and savant. There I had my collateral initiation, so to speak, and the Sikh sage launched me into a life of imagination with a touch of his noble hand on my head.

I was soon to drift away to other ideologies and pursuits at college, but the poet’s impress was a part of my poetics when I published, 43 years later, “Studies in Punjabi Poetry” (Vikas Publishing House, New Delhi 1979).

This, again, rings a bell in my mind, and I find myself in our ancestral Jhelum house in a winding, narrow, blind street close to the river. It’s winter evening, and after an early round of prayers and dinner, the family gathers around father’s bed. Tucked in woollens and quilts, the children are treated to readings from Bhai Vir Singh’s romances of Sikh life and lore, “Sundari” and “Satwant Kaur“, in a serial manner.

For it was father’s view that the nexus between word, vision and valor had a deeply spiritual character, and he wanted his children to imbibe such a lesson under his benign paternity before the world of commerce and career would close in on us. That was the way, he thought, to prepare us for the life of the spirit in accordance with the Sikh world-view.

We are now approaching the end of this story of a person who, till the age of 67 or so, when he died in the highest Sikh tradition in September 1947 at Jhelum, had virtually proved his being and his personality.

And the story returns me first to my father’s own paternity and lineage.

Son of an army havildar, and bereaved when young, father set out from our village, Vahalee (Jhelum District), a medieval kind of country place with a huge gothic structure (Sardarn-du-mari) and a crazy rambling group of hamlets, huts and stone-houses – all gingerly placed atop a small undulating hill.

And he always remembered with pride that his great grandfather, Sardar Rattan Singh, a high ranking cavalry officer in Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Khalsa army, had declined the Maharaja’s offer of a big jagir, saying that the entire kingdom was a Khalsa Commonwealth, and that such jagirs were redundant extravagances.

The great ancestor, it may be added, was killed in battle in the famous encounter with the British Army known as Mudki-ki-Larraee.

An earlier story links the Maini family with Raja Fateh Chand Maini of Patna Sahib and the childhood association of Guru Gobind Singh with that House.

And thus to the appointed or ordained day of destiny in September 1947, a day for which his life, his work and his vision had, since his youth, prepared and primed him. And to such persons, to stand up in the midst of flame and fire, and give battle to the last ounce of their moral energies, death in action and in the service of a great cause, comes as the ultimate test of their being and becoming, of their quest and arrival.

And it’s in this state of his roused mind and puissant soul that father achieved his mukti or nirvana.

I reproduce below some extracts from my long-article, “An Agonized Spectator of Holocaust” commissioned by the Tribune in its series on the 50th anniversary of the Partition of Punjab.

* * * * *

… And then one awful evening in September, I saw my mother, my brother alight from a truck in front of the Khalsa College gate at Amritsar. No, I had lost my father, I was soon to learn. He had not made it, for he too, as he believed, had a tryst with destiny -- a tryst authenticating his Sikh traditions of battle, engagement and sacrifice when challenged, or pushed to the wall. He was a man cast in the heroic mold, and he lived up to the top of his bent.

And the story of his martyrdom as the leading Punjabi daily in Urdu, Ajit, Jullundur, said in an editorial later, was in the classic vein, redolent of the great Sikh sagas, it was, in a manner, the summation of all his energies of thought, purpose and deed.

There are some natures that are called upon – moments of spiritual or moral crises – to life to the full pitch of their potentials. Difficulties, hardships and sufferings then become part of the developing vision, and begin to act as agents of action and redemption. Indeed, father’s entire life, in a manner, constituted a metaphor of spiritual gaiety in the midst of ideals. And this concept of sadaa vigaas, or spiritual gaiety that we find apotheosized in the poetry of the two of the great Sikh savants, Bhai Vir Singh and Prof. Puran Singh, is something that Sikh history and scriptures have sanctified time and again.

It is not therefore surprising that when everyone was fleeing Jhelum for dear life, he decided to stand up and face the coming tragedy. No, he could not desert the post of duty. Which was, as I learnt later, to see the weak and the helpless quit first before he could even think of his own safety.

And that’s how he and my family remained on that fateful day of his killing by an incendiary Muslim mob of hooligans on the anniversary of India’s freedom.

It is something that I picked up, piece by piece, from the story narrated to me by my mother and younger brother, for they were the sole survivors of that heroic scene. It appears from their account that father’s high profile as a freedom fighter, as a Sikh leader worthy of repute and as a doughty warrior on behalf of lost causes had apparently brought the mob to our door. He was then considered a prime target, a thing that the assailants remained to regret woefully.

For, with a nephew’s gun, father kept firing over two hours to keep the bellowing mob at bay, felling many in the process. At the age of 67 he took up the gun again after passage of 40 years or so from his hunting days in the hills of Vahalee, a whole dream behind him.

But Providence so wished and he only left his post when the house was going to be set on fire, and a passing company of British soldiers prevailed upon the besieged families to come out. It was then that a sneak sniper perched on top of a tree perhaps let loose a volley of bullets, and my father, hit in the thigh, could manage to limp his way to the police-station, a hundred yards away.

Later that evening he breathed his last with the name of his Creator on his lips. Tossed, reportedly, into the Jhelum river along with scores of others slaughtered on that day, his bones, finally, came to rest in the waters which in the years of his health and vigor, he used to swim across from one side to the other, and his soul, I trust, found its true and happy habitat, in the House of Waheguru.

In his swan song, “The Four Quartets“, T.S. Eliot initiated the poem, ‘East-Coker’ thus:

“In the beginning, is my end.”

My father knew when he set out from his village in his late teens around the turn of the century that he had a long journey ahead, full of challenge and promise. He never faltered once; he knew his direction and his bearings. He vindicated his ‘beginning’ in the 'end,' and his “end” in the “beginning.”

It was truly a consummation that a Gurmukh sought in full faith and wakefulness.

[Professor Darshan Singh Maini, was a prolific writer and a scholar of English Literature. He was Head of the English Department, Punjabi University, Patiala. This piece was published earlier in The Sikh Review. Edited here for sikhchic.com.]

Concluded

To read an earlier story -- "My Grandfather’s Story", please CLICK here.

[Inni Kaur is the author of a children's book series, "Journey with the Gurus". She also serves on the board of the Sikh Research Institute.]

August 14, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Arvinder Singh (New York, USA), August 14, 2013, 11:25 AM.

The heritage and history of Sikhs is truly remarkable and utterly humbling. We can only wonder how much our ancestors achieved and by the grace of our Gurus towered above all. Yet, they did not leave behind legacies of pride and pillage. Instead, they left us legacies and examples of supreme sacrifices, humility and tolerance. We need to emulate them and their deeds by following the Guru's teachings. A true Sikh should be humble, and stand for truth, justice, equality peace and love.

2: Harbans Lal (Dallas, Texas, USA), August 17, 2013, 7:00 PM.

Inni ji, you brought many events and personalities afresh to mind. Some of them I knew and experienced personally. I did not realize the full extent of your own rich heritage. Professor Darshan Singh was a close friend who showered his love whenever I visited him, even when he was not feeling well. During my last visit he autographed and gave me couple of his books. I really miss him. Please continue writing.