Partition

The Partition of Punjab:

The Story of My Dad

Part I

INNI KAUR

Thursday, August 15, 2013 marks the 66th anniversary of the Partition of Punjab.

It’s strange how certain events have the power to jolt one’s memory.

For me, August 15, 1947 falls in that category.

66 years have gone by since the Partition of Punjab and the creation of India and Pakistan. Yes, it happened long before I was born.

Yet, every August I go through a strange nostalgic feeling.

Mind you, I have never lived in India. Yet, I feel a deep sense of loss. Not quite sure why.

I often ask Dad whether he misses his ancestral homes in Chakwal and Jhelum.

“What’s the use? It’s all gone. There is no point in remembering,” replies my very practical father.

But, I do remember. And I sort of grieve.

On one visit back home I insisted that he tell me what happened to the family during Partition. It was not easy to convince him. My powers of persuasion were tested. But, finally, he relented and the recording sessions began.

The following is the story of my father, Bawa Gurnam Singh (b. 1931 – Chakwal, Dist. Jhelum, pre-partition Punjab), son of Hari Singh and Harnam Kaur. As told to me by my father:

* * * * *

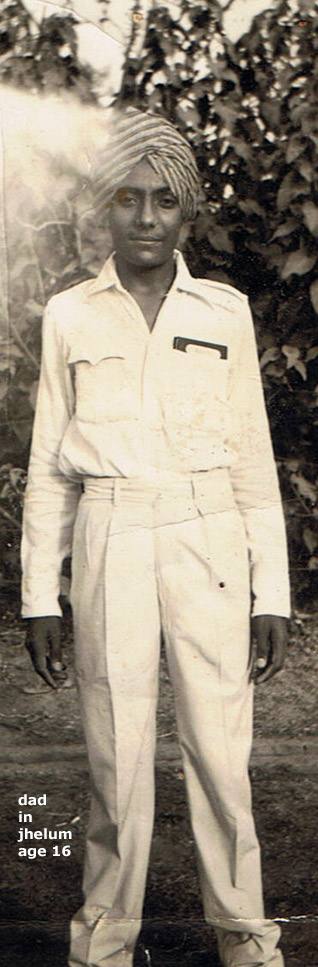

You know, during Partition, I got saved twice in one day, starts Dad. I was 16 years old and was staying with my Nana ji (material grandfather) Mehtab Singh Maini in Jhelum. He was a Congress leader and was constantly in and out of jail.

While it was a difficult time, it was also an interesting time. Every important leader used to stay at nana ji’s home when in town. Nana ji had a big house. The main house was for the family and the outer house was for the guests. There was always someone staying there.

At that time, in Jhelum, there used to be daily protests against the British Government. The women led their own processions - nani ji (maternal grandmother) also marched. The youngsters were the most vocal. I was actively involved in politics and therefore subject to several police beatings. It was their way of getting back at nana ji.

“Dad, how old were you?”

I was in Grade 7 and 8, and was studying at the Khalsa School in Jhelum, when the beatings took place. The police used to come to our school, pick me and a few other boys, take us to the police station, thrash us and send us back home. I remember one particular beating. The police men were beating us lightly. I guess because we were children. A British Officer saw that. He immediately came over, took the cane from the Indian police officer and thrashed us. I still remember that beating. But that was life, in those days.

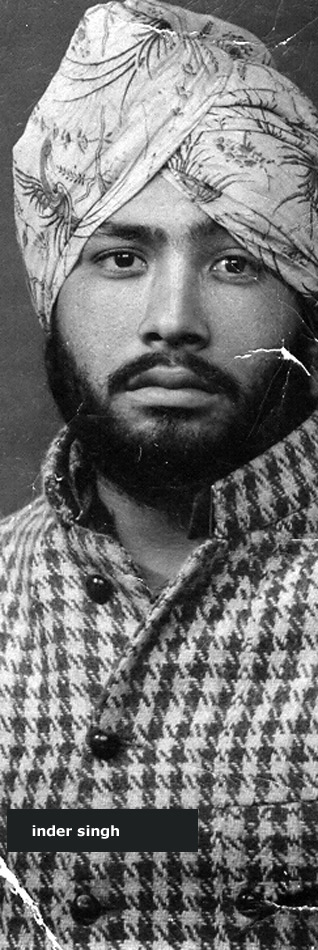

In August of 1947, I was in the 10th grade and was back in Jhelum for the school holidays. Nana ji’s home was the political hub. Everyone came there to get and give information. One day, Inder Singh Gadhok and his younger brother Dilbagh Singh came to inform nana ji that they were leaving for Ambala. The Muslim community had hired them to bring back their Pir (saint) who was living there. The two brothers along with Sri Ram the driver were leaving the next day by bus.

I knew Inder Singh very well. He was the don of Chakwal. Nobody dared to cross him. He loved and respected my taya ji (father’s older brother - Bawa Jewan Singh) a lot. Inder had made sure that everyone knew that our family was under his protection.

“Dad, a don?”

Yah! Like today’s mafia. Inder controlled a large part of the bus transportation in Punjab. I used to ride for free in the buses because of him.

I’m flabbergasted. I make a mental note: I have to find out more about Inder. But not right now.

I was eager to see the Independence Day celebrations in Delhi. My older brother Amrik was studying at the Delhi Polytechnic and was staying at a hostel in Kashmiri Gate. I begged and pleaded with nana ji to allow me to go with Inder up to Amritsar. From there I would catch the train to Delhi. With great reluctance, nana ji agreed.

The next morning I left. Inder drove the bus up to Lahore. When we entered Lahore, he told Sri Ram to take over as we were entering the Muslim area. So, Sri Ram drove and the three of us lay down on the seats hidden from public view. But Sri Ram did not know the way and was constantly asking Inder for directions. He came to a critical junction and did not know which way to turn. Inder got up to see where we were. At that moment, the people on the ground saw that there was a Sardar on the bus. They started shouting and before you knew it a small bomb was thrown at our bus. It hit the rear wheel tire of the bus. The tire exploded, causing a huge sound.

A large Muslim crowd immediately surrounded the bus. Just then, an army unit was passing by and stopped to see what was happening. The crowd told them that we were terrorists and were throwing bombs at them.

Inder, of course, protested. The army officer decided to search our bus. When he opened Inder’s suitcase, a photograph caught his eye. He asked Inder how he got this photograph. Inder told him that it was his childhood photograph. The officer looked shocked. It turned out that he was Inder’s childhood friend Hussain who had left Chakwal many years ago. Hussain was thrilled to reconnect with Inder.

Under Hussain’s protection, the bus tire was repaired and we were escorted to Mughalpura, a part of town which was Sikh and Hindu dominated. Hussain said that we would be safe here and that we should leave for Amritsar from there.

We spent that night at Inder’s relative’s home in Mughalpura. In the middle of the night, Inder woke us up. He said that he had an eerie feeling that we should leave right away. He was sure something bad was going to happen. He even insisted that his relatives leave with him but they refused, assuring him that they were safe.

The four of us got on the bus and left for Amritsar immediately. When we reached Amritsar, we heard that Mughalpura was attacked by the Muslims and everyone was killed. We had narrowly escaped death.

Inder dropped me off at the Amritsar railway station and proceeded on to Ambala. At the station, I could not get a ticket for Delhi. The Government had stopped all trains going into Delhi. I guess they did not want refugees coming into the capital and disrupting the celebrations. I sat at the train station for four days. My luggage and money were stolen. My passport and a few photographs that were in a muslin bag hanging from my neck under my shirt were all that I had left. Nana ji had insisted that I carry my passport that way. You know, I had a British Indian passport and it was stamped in red: ‘Son of a revolutionary.’

“Wow! ‘Son of a revolutionary‘? How did you feel about that, Dad?”

Great! It was like a badge of honor. The people who used to help the British Government got titles like ‘Sardar Bahadar,’ ‘Sardar Sahib,’ ‘Khan Bahadur,’ and ‘Khan Sahib,’ and many such phokat -- hollow -- titles. Local equivalents of ‘Sir’ and knighthoods, they were. There used to be weekly processions in front of these people’s homes and the slogan was: “Todhi baccha hai, hai.” They were gaddaars - traitors. We were the real heroes fighting for our freedom.

“Dad, what did you do for food, you had no money?”

Food was no problem. There was free food available at the station for the refugees. On the fourth day, a really long train with a large sign saying ‘Delhi’ arrived at the station. Everyone, including me, boarded that train thinking we were going to Delhi. But, that was not the case. The train was heading for Patiala.

I knew that my mother’s sister Rani and husband Amar Singh Ghai lived in Patiala, but I did not have their address. Talk about being lucky! As I got out of the train station, a tongawala (a horse-carriage driver) stopped me. I recognized him immediately He was Kala from Chakwal. I told him all that had happened since I had left Jhelum. He insisted that I stay with him and that I ride with him until I found my relatives. I hesitated at first. But I had no choice, so I agreed.

“Dad, why did you hesitate?”

He was a dangotara.”

“Who, what, is a dangotara?”

Dangotras in Chakwal were beggars. A few of them did odd jobs. Every Saturday they would go begging door to door. They used to carry a small bowl, which had mustard oil and a small idol in it. People would put money in their bowls. But Kala did not beg. He owned his own tonga (horse-carriage). In 1942, when we came from Zaidan to get my eldest sister Jasbir bhen ji married, my father hired Kala for the entire month of the wedding. He was in charge of getting everyone from the train station as well as delivering all the supplies from the market to our home. So, I knew him well.

Kala took me to his home which was a small two-room house. His wife and children were also there. I still remember he gave me his best charpai (cot) to sleep on. He looked after me well.

On the third day of riding around Patiala, I spotted my uncle carrying a bag of vegetables. I immediately asked Kala to stop and ran to my uncle. My uncle was shocked to see me and took me home. I stayed with my aunt and uncle for five days. They were really very, very nice to me. They got clothes made for me, gave me money and bought my train ticket to Delhi.

When I arrived in Delhi, I went straight to my brother Amrik’s hostel in Kashmiri Gate and knocked on Room 302. Amrik opened the door and was stunned to see me. Are you alive? Are you really alive? He kept asking. I was surprised by his question.

He then told me that nana ji had read in the Urdu paper Milap that the bus I was on was attacked in Lahore and everyone was killed. The family thinks you are dead. He rushed to the post office and sent two telegrams. One to our parents in Zaidan and the other to nana ji in Jhelum informing them all that I was alive. Years later, I found out that my parents had said my antim ardas (final prayers), in Zaidan.

For two months I stayed with Amrik at his hostel. It was against hostel rules. But there was nowhere else I could stay.

“Dad, what was Delhi like in August of 1947? What did you do for those two months?”

“I don’t know what was happening in all of Delhi. I can only say what was happening in my area. It seemed calm. I did not see any organized mobs. Though, I did see a few stabbings. Amrik’s friend Sayali advised me to join the NCC (National Cadet Corp.). So I registered myself at the Kashmiri Gate Police Station which was within walking distance from the hostel.

Every morning at 8 a.m., I would go to the police station. Two policemen and I would then go in a jeep to rescue Muslims. We used to go door to door, as he houses in Kashmiri Gate were in small lanes. I remember one time entering a house that looked empty. But it was not. There was a young girl around 14 - 15 years old hiding there. When she saw me she started screaming. With great difficulty, I calmed her down and told her that I was there to help, not harm her. Her entire family had left without her. We took her back to the police station and from there she was taken by bus to the Purana Qila (Old Fort) Refugee Camp.

My two months in Delhi were spent like this. I used to have lunch at the police station and at night I would sneak back into the hostel. I got caught the day Amrik went to Rohtak. The warden insisted that I leave the hostel immediately. Amrik’s friends did not take to this very kindly. They held their ground and said that I was not to leave. To keep the peace, the warden took me to his home. I stayed with him for three days until Amrik got back. The warden’s home was far nicer than the hostel.

Amrik had gone to Rohtak to see if our mama ji (mother’s brother) Darshan Singh Maini and his wife Tejinder, were willing to have me stay with them and complete my studies. They of course agreed. Darshan mama ji had just gotten a job at the Government College. That was the good news.

Then Amrik told me that nana ji was dead. My whole world came to a stand-still. I adored my nana ji. He was the biggest influence in my life. He really loved me. I learnt so much from him. It is because of him that I joined the Congress Party. You know, even though my father was an Akali.

Continued tomorrow ...

To read an earlier story -- "My Grandfather’s Story", please CLICK here.

[Inni Kaur is the author of a children's book series, "Journey with the Gurus". She also serves on the board of the Sikh Research Institute.]

August 12, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Harinder Singh (Bridgewater, New Jersey, USA), August 12, 2013, 11:44 AM.

I often wonder why Sikhs are not celebrating Babbar Akalis, the longest movement in early 20th century towards freedom. Our subservient attitude and worldview only allows highlighting medal winners who were the Queen's (or King's) subjects in the pre-partition era.

2: Ek Ong Kaar Khalsa (Espanola, New Mexico, USA), August 12, 2013, 10:39 PM.

What a window into another time and another world. Thank you for sharing this.

3: Manpreet Singh (Hyderabad, India), August 13, 2013, 5:56 AM.

Have come to this forum after a couple of months and read the backlog in 4 days. Thanks a lot for sharing this beautiful tale. I am even keen on knowing more about S. Inder Singh. For me August 15 is an ominous date when we Sikhs lost our motherland to Hindus and Muslims. I somehow don't get the logic that why were Sikhs fighting for the freedom of Hindustan when we had lost our land (Punjab) to Britishers. Am I missing something here? When did this deviation take place that instead of getting Punjab freed from Britishers we started fighting for the freedom of Hindu-land? I know the likes of Nehru, Gandhi, Patel duped Sikhs post independence. But, why were we fighting for the independence of Hindustan and not Punjab? From when did we Sikhs started loving the Hinduland and not Punjab? Don't give me reason that we are selfless people and all that. There has to be some incident in history which changed our thinking as well as outlook towards freedom for Hinduland and Punjab. Can someone please explain me this?

4: Akaldev Singh (Southall, England), August 13, 2013, 2:34 PM.

I was 14 the day the independence came to both Pakistan and India. We were celebrating the gurpurab of the Fifth Guru Sahib, when a burnt-out bus drove into Ludhiana where Muslims were well entrenched because of their belief that Ludhiana should in be Pakistan all the way up to Delhi, an idea which never materalized because of the Sikhs opting for India. In Ludhiana at Millerganj, we were putting up gates for our protection and making odd weapons, but across the railway lines the Muslims had all the guns to fire on us. In Gobindpura Mohalla, the headman was making speeches to calm down Sikhs who were under pressure to act. Sardar Kharak Singh came to tell Ludhianvees that the defense of Sikhs beyond Lahore was non-existent and a big crowd in Ludhiana went beserk. When a train-full of dead bodies arrived from Pakistan, the frenzy on our side was so immense that I felt unsafe and all young men went to my nanka pind (village of my maternal grandparents) near Delhoun where groups were set up to defend the village. The local Muslims were collected and dropped off safely in a camp near Malerkotla. The next thing, after much killings, was a rain so strong that many people were just drowned in the rivers and a nulla (canal) we called Buddha Nalla and the canals going through villages were full of dead bodies and on one it was written in Urdu: PLEASE DO NOT STOP THIS DEADMAN AS HE IS GOING STRAIGHT TO PAKISTAN. The carnage of poor people were greater in India than in Pakistan though property lost by Sikhs were greater than the poor Pakistanis. The spirit of the Sikhs was high, while the Hindus were afraid of doing anything and in many cases a few Hindus were slain and it was decided that all Hindus must wear karras for identification purposes as the growing of a bodee (tuft of hair) may take time. I was studying in the 6th grade in the Khalsa National High School and we all went on strike when we heard that a Sikh on a tonga traveling in Lahore had been murdered. The other high school, Malwa Khalsa School was not in a mood to let the classes go but a clever move by one of our friends to sound the gong did the trick and the school was on the war path. The next day my brother and I were punished for this action but we enjoyed the good act since then I am a nationalist. General Mohan Singh from the Indian National Army was picked to train the local militia to protect Punjab from further attacks from Pakistan and a plea to the governor of Punjab to issue us basic rifles for training was refused and we joined the National Cadet Corps which had training under the command of army camps in Ambala where we received basic army training.

5: Wahab Talib (Chakwal, Punjab, Pakistan), August 11, 2014, 6:35 AM.

The people of Punjab here still love the other side of Punjab (in India). Let's stop fighting. I don't know for which purpose we are fighting with each other. Our culture, our lifestyle are same. For God's sake, let us stop killing innocent people of both countries.