History

Chasing the Dragon:

The Diaspora Diaries, Vol 5

SARBPREET SINGH

The Diaspora Diaries is a series of articles that I am writing as I collect oral histories and stories for ‘Lions In The West’, a work of non-fiction, that documents the one hundred and twenty year history of the Sikhs in America.

On October 29, 1909, The Straits Times, a newspaper in Singapore, ran a story with the following headline: “Shanghai Sikh Police; Result of Disobeying Order of Deportation; Judge's Severe Comment”.

The story was about “Eleven Sikh policemen,’ who had been hauled before a judge to explain why they had not complied with a deportation order that they had received after being found guilty of insubordination. The Sikhs were braided by the judge, who felt that they had ‘disgraced the character of the Sikhs’, the general perception of which was apparently at odds with their behavior. The men were asked to put up a large sum of money as security, pending the execution of the deportation order.

The article went on to report the testimony of Captain E.I.M. Barrett, a British officer in the Shanghai Police, who said that a pattern of insubordination and misconduct had been observed of late among the Sikh policemen and that their actions seemed to be very deliberate!

As I started researching the arrival of Sikhs in the US in the late 1800s, many of the accounts I discovered seemed to suggest that most of them had come to the US and Canada from Shanghai or Hong Kong. This piqued my curiosity as I had never read anything about Sikhs in China in the 19th century, even though their exploits in the British armed forces in World War I are well documented.

This search led me to discover one of the darkest chapters in the history of British colonialism which, I am sure, is well studied in China but seems to have been conveniently bowdlerized from collective memory elsewhere.

In June 1840, a fleet of British warships sailed into China's Pearl River Delta and unleashed a barrage of violence, overwhelming China's weak coastal defences and bringing the country to its knees. This was the First Opium War in which thousands were killed in the name of free trade.

Trading opium into China was a lucrative but illegal business and two Scotsmen involved in the trade played a crucial role in the Opium Wars. William Jardine, a former ship's surgeon turned private trader from Dumfriesshire, and James Matheson, a trader from Sutherland, became business partners after first meeting in a Chinese brothel.

In 1832 they formed Jardine, Matheson and Company, based in Canton, southern China (now known as Guangzhou), in the 13 Factories district - the only area of the city where foreigners could trade. They traded opium for tea, for which Britain had acquired a great thirst.

By the end of the 18th Century Britain imported over six million pounds of tea per year from Canton.

At first Britain struggled to maintain the trade as China would accept only silver as payment. Wedgewood pottery, scientific instruments and woolen goods were among the items Britain offered to trade, but all were declined. Over a 50-year period, Britain paid £27m in silver to the Chinese, but sold them only £9m of British goods in return.

Tea was becoming unaffordable and there was seemingly little way to make money in China.

But British traders saw an opportunity from the conquest of Bengal which had a large harvest of opium. Opium had been banned in China even though it had been used in Chinese medicine for thousands of years. The sale and smoking of the drug was banned by Emperor Yongzheng in 1729, but 100 years later there was still a strong demand and the British were exploiting it.

By 1836, 30,000 opium chests were arriving in China each year from India. Jardine, Matheson and Company was responsible for a quarter of those. By flouting the trade ban on opium, Britain found a way to increase its earnings from China and became the biggest drug dealer that the world had ever known, devastating an entire nation in its quest for wealth.

The British opium trade had not gone unnoticed and in 1839 Emperor Daoguang declared a war on drugs. A series of raids were ordered on the Western traders. Goods with a value of £2 million were seized, including 42,000 opium pipes and

20,000 chests of opium.

Incensed by the seizures, William Jardine left Canton for London, where he lobbied the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, to strike back at China.

With opium responsible for a significant part of British India's tax revenue, it didn't take long for the government to send in the navy. In June 1840 the British fleet of 16 warships and 27 transports carrying 4,000 men arrived in the Pearl River Delta, near Humen. The Chinese were prepared, but their antiquated defenses were no match for the British. Their static canons and armada of war junks were destroyed in just five and a half hours.

Over the next two years the British navy travelled up the coast towards Shanghai. The British bombardments resulted in a considerable loss of life - between 20,000 and 25,000 Chinese were killed. Britain lost just 69 men. The Chinese Empire was shattered.

In August 1842 aboard HMS Cornwallis, near the town of Nanking, the Chinese signed what became known as the "unequal treaty". They agreed to open five ports to foreign trade and pay 21 million silver dollars to the British government, as compensation for loss of opium earnings and the cost of war.

For the British the highlight of the deal was the acquisition of Hong Kong Island, which would be used as a hub to increase trade in opium with China.

In the mid-1850s, the British sought to renegotiate their commercial treaties with China. They wanted the opening of all of China to their merchants, an ambassador in Beijing, legalization of the opium trade, and the exemption of imports from tariffs.

Unwilling to make further concessions to the West, the Qing government of Emperor Xianfeng refused these requests and the tensions escalated into the Second Opium War after the British formed an alliance with France, Russia, and the United States.

In 1857, after dealing with the Sepoy Mutiny in India, British forces arrived at Hong Kong. The governor of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, Ye Ming Chen, ordered his soldiers not to resist and the British easily took control of the forts. Pressing north, the British and French seized Canton after a brief fight and took the Taku Forts outside Tianjin in May 1858.

Seeking peace, the Chinese negotiated the Treaties of Tianjin. As part of the treaties, the British, French, Americans, and Russians were permitted to install legations in Beijing, ten additional ports, including the then small fishing village of Shanghai, would be opened to foreign trade, foreigners would be permitted to travel through the interior, and reparations would be paid to Britain and France.

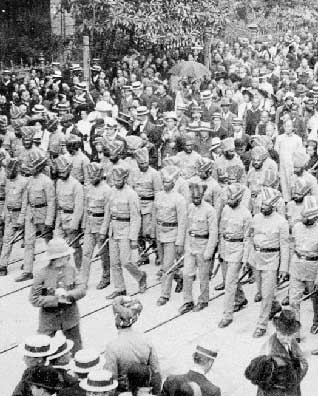

The British force that fought in the Second Opium War included men from the 15th Ludhiana Sikhs, an infantry regiment in the British Indian Army.

The Sikh Empire, under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh was the only power that could stand up to the might of the British in India. Rather than confront the British, Ranjit Singh sought an alliance with them, which was sealed by the Treaty of Amritsar, signed in 1809. After his death in 1839, the Sikh Empire collapsed completely by 1849, after the British defeated Sikh forces in the second Anglo Sikh War. The Punjab was annexed and became part of the British Raj.

Sikhs very quickly became staunch allies of the British and, along with the Gurkhas, became the backbone of the British Indian Army.

The 15th Ludhiana Sikhs was created in 1846 and was then known as The Regiment of Ludhiana. It was deployed in Benaras during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 and it remained loyal to the British and played a key role in the suppression of the mutiny.

The 15th Ludhiana Sikhs played a key role in defending the city of Shanghai during an uprising known as the Taiping rebellion.

The Shanghai Municipal Force was established in 1854 to protect the Shanghai International Settlement which transformed the sleepy fishing village into a hub of commerce. Composed initially of Britons, it was expanded to recruits of other

nationalities.

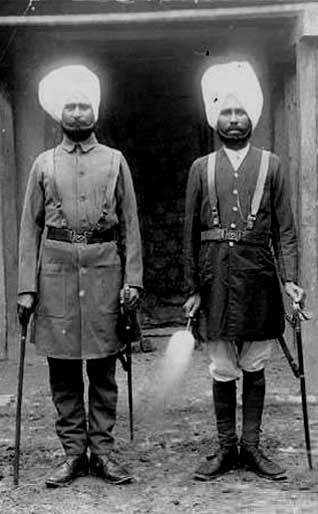

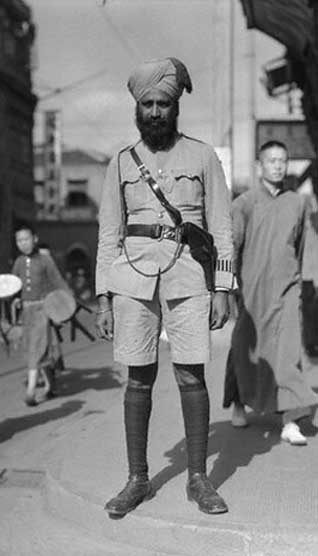

A Sikh branch of the force was established in 1884. Sikh policemen would be brought to China at the expense of the British authorities, and would in exchange sign a five year bond.

In a paper, titled “The Raj on Nanjing Road”, Isabella Jackson describes how Sikhs made their way to Shanghai and other parts of the Far East:

The men recruited to the Sikh branch were almost without exception ex-sepoys from rural families with limited resources. Migration was seen as an honorable solution to financial problems faced by such families as the fragmentation of land-holdings and rising land prices placed their position under threat. Competitive pay (up to five times that offered in the Indian Army) and conditions, including nine months’ leave on half pay with passage to Punjab on the completion of a five-year term, made the Shanghai Municipal Police a tempting option for Sikhs looking for such work.

The preferred method of recruitment was selecting men -- or, after 1905, having men selected by the British Indian Army recruiting staff -- directly from Punjab. This was an effort by the Government of India to exercise control over the spread of Indian subjects abroad, but as Indians continued to make their own way eastwards in search of work, the Shanghai Municipal Police, like forces in Malaya and elsewhere, also recruited locally.

Those who were not taken by the Shanghai Municipal Police generally found employment as watchmen for private firms, although there also existed a ‘floating population’ of destitute Indians, many of them Sikhs, which caused concern to the municipal authorities.

The presence of the Sikhs in Shangai was not accepted easily by the local population. Jackson describes the clash of cultures as follows:

The Sikhs’ turbans, beards and dark complexions certainly made a strong impression on the Chinese of Shanghai, featuring in every description of these hated men. In 1917 one magazine published a mock folk song that opens: ‘Every year, the Sikh policeman’s turban is red. Every year, the Sikh policeman’s head is black’ and bemoaning how ‘completely foreign’ these men seemed in the Chinese city.

A cartoon in the1940 Chinese Art Association magazine identifies a Sikh with a Scottish highlander and an English inspector as ‘famous things in Shanghai’, with a caption describing the Sikhs as having ‘faces covered with hair’.

These examples are typical of the kind of images found in the contemporary popular Chinese media; stereotypical views remained fairly static throughout the period of Sikh employment in the Shanghai Municipal Police.

Other examples of Sikhs in Shanghai appearing in popular culture include Hergé showing a a Sikh directing traffic in Tintin’s Adventure in The Blue Lotus, as well as a depiction of three bloodthirsty Sikhs who are ordered to give Tintin ‘a spot of corrective treatment’ in the municipal prison.

Kazuo Ishiguro, in his novel When We Were Orphans uses a description of Sikh policemen stacking sandbags against the threat of Japanese aggression set the scene as a detective mulls over his case at the British Consulate in Shanghai.

Bruce Lee attacks a Sikh guarding the entrance to the Shanghai Public Gardens for refusing him entry in Fist of Fury.

The Sikhs of Shanghai had successfully found employment overseas, but they became increasingly aware of greater opportunities beyond China. In particular, stories of Sikhs in Siberia and Canada earning as much as $100 a month, many times the salary of a policeman in Shanghai, caused a tremendous stir.

The Sikh Branch of the Shnaghai Municipal Police went on strike when a demand for a pay raise was rejected in September 1906. Some policemen who had served out their bond resigned and left Shangai to seek their fortune in Panama, where work had started on the Panama Canal and the Pacific Northwest. Others bound by their contracts sought dismissal for misconduct or produced false letters from home seeking termination to attend to urgent family business.

The fall of the Sikh Empire to the British, the alliance between the Sikhs and their new rulers, the British Opium trade in China and the Opium Wars, the establishment of ports Like Shanghai and the recruitment of Sikh policemen: all these seemingly unrelated historical events conspired to create the conditions that resulted in early Sikh migration to North America.

As I continue my research for Lions In The West, I am eager to hear first-hand stories that any of my readers might have stumbled upon from family members whose ancestors sojourned in the Land of the Dragon on their way to other parts of the world.

November 12, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: SSN (USA), November 12, 2013, 11:52 AM.

Young turbaned Sikh here. Was in China for a two-week vacation earlier this year. 1) Almost all (if not all) Chinese think all Indians wear turbans; and 2) that Sikhs are an ethnic group. I was shocked how little they know about and of Sikhs. It is worthy of note that, a) All males were required to keep long hair during the Ming era. b) Sikhs have been in Hong Kong and China as soldiers and policemen since late 19th/early 20th century. c) Most Chinese have a better sense of history than most westerners; but have only a slight knowledge of 1984. In all, I was better treated in China than India. Unfortunately, Sikhs are not spreading awareness of Sikhism. This is not a recent trend, sadly.

2: Baljit Singh Pelia (Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.), November 12, 2013, 12:06 PM.

In depth research will help us connect the dots of our history. The Sikh nation's finest were scattered all over the British colonies and used to further their trade and occupation, both mostly illegitimate. If viewed objectively, dispersing the Sikh forces was the process of dismantling the great Sikh nation, an indigenous creation of the people of the sub-continent brought together by the Gurus over a period of two and a half centuries, so it would never rise to be a power to challenge Great Britain again. After India's independence, these facts should have been studied by scholars and historians and would have been helpful in reassembling and expanding the secular Khalsa nation that brought pride and prosperity to all. I keenly look forward to the follow up of these well researched articles and applaud S. Sarbpreet Singh ji's effort.

3: Sukh Singh (British Columbia, Canada), November 12, 2013, 5:27 PM.

My nana ji's father came to Vancouver, Canada to work in the lumber industry, then went to Singapore where he served as a policeman. He spoke/wrote Malay fluently. He also went to university there. As World War II broke out, Japan was at the doorstep of Singapore and bombs were exploding everywhere; he was on the last flight out. I'm still researching through the family for more information.

4: Sunny Grewal (Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada), November 12, 2013, 10:37 PM.

The British Empire may have been responsible for the loss of Sikh sovereignty, however, the Sikhs were able to use the channels of the empire to migrate out of India and establish a diaspora all over the world. The reason I am sitting in the west writing this comment is because of Sikh pioneers who during the colonial period migrated out of British India and established settlements which would blossom into large Sikh communities. Think about it like this, there are around 30 million or so Sikhs in India, and over a billion Hindus yet in Canada the number of Sikhs and Hindus are pretty close, each numbering over a million (According to the latest census report based on religious affiliation). Sikhs were able to use the British Empire to leave India and establish a tradition of migration for future generations. Could you imagine how much worse we would be off if our people didn't have such an affinity for adventure and entrepreneurship?

5: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), November 15, 2013, 6:44 AM.

Very interesting article. My own family decided to leave Amritsar in 1925 for the United Kingdom, because of the 'greatness' of the British people and their fairness and non-corruption. However, we are back in Amritsar on a regular basis. Perhaps, under a proper Sikh administration, Punjab will flourish and become the world's 'soney ki chirriya' once again!