Books

Engaging With Life:

Amandeep Singh Sandhu

An Interview by ROSALIA SCALIA

A recent trip to India finds me sitting in Delhi’s historic Khan Market in an Italian restaurant run by Tibetans called "The Big Chill".

Over hot chocolate, tiramisu and chocolate Oreo cheesecake, the Sikh-Indian novelist Amandeep Singh Sandhu talks about why he loves the character Gollum from Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (“Gollum can’t let go! He can’t let go of the ring, and that is the condition we all find ourselves in at some point or another”) and his mini-migration experiment with red ants, among other topics.

The red ants, drawn to the fruit trees under which Amandeep parks his car, somehow find their way into his car, and thus begins their inadvertent migration from one end of the city/state that comprises Delhi and New Dehli where his office is located, to the other end of the National Capital Region where he lives. For the ants, he quips, it’s a great distance.

“Delhi is a city and a state and the nation’s capital region. You can travel two hours, three hours and still not leave it.”

It’s fitting that Amandeep's inadvertent red ant migration micro-experiment doesn’t escape his keen eye and even keener wit: currently, he’s hard at work on his third book, tentatively titled "Ticket to Canada", an exploration of human migration from the Punjab - India’s veritable bread basket state - to points west, namely North America.

Born in Rourkela, in India's state of Orissa, Amandeep, 38, has lived in Orissa, Uttrakhand, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Karnaataka, and currently calls Delhi home.

Like many Americans, his love for story, books and literature developed as a youngster via comic books. Indian comic book heroes such as Badal and Chacha Chaudhry captured his attention as did Phantom, Spiderman, the Green Hornet, and other famous crusaders.

Despite the prevailing rural Sikh family culture into which he was born that relegated the study of literature as an “unmanly” and “impractical” career choice, Amandeep prevailed, earning his first Master’s degree in Literature from the University of Hyderabad in 1996 and his second Master’s in Journalism from the Asian School of Journalism in 1997.

Like many writers-in-formation, he held a variety of jobs on the way to becoming a wordsmith, including farm hand, woolen-garment seller, a shop assistant, a tuition master, teacher, journalist with The Economic Times, a technical writer with Novell, Inc. Oracle, and now at Cadence Design Systems.

“Literature, for me, is an understanding of the essential human struggle to become complete. I write to understand myself and my world, and to sleep peacefully at night,” he says.

Still, the road from reader to literature student to writer came with the familiar struggle of daily blank pages during which “I couldn’t write a single sentence in any language,” says Amandeep, who is fluent in English, Punjabi and Hindi, and also speaks Urdu, Oriya and Bengali.

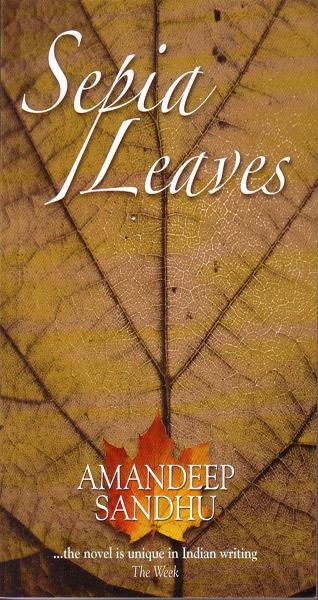

Published in 2008 by Rupa & Co., India’s largest publisher, Amandeep's first novel - Sepia Leaves - earned high critical acclaim. An autobiographical narrative - a fiction that alternates between memory and reality, Sepia Leaves chronicles the impact of a mother’s schizophrenia on her only child - a son - her husband, their entire family, friends and even society. By its existence - exploring mental illness, a topic often swept under the carpet in many cultures - coupled with its structure and lyricism, Amandeep captures a trajectory that many families struggling with mental illness face as they traverse from diagnosis to acceptance.

But Amandeep travels beyond, demonstrating how grace under pressure can result in resilience, hope and love.

The novel earned him critical acclaim and a plethora of speaking engagements, and is available in bookshops across India, while his second novel, Roll of Honour, is expected to hit Indian bookshelves in Spring 2012. Although not yet available in North America, readers can buy Sepia Leaves online via http://www.flipkart.com/books/8129113708.

Below is a snippet of the conversation with Amandeep Singh Sandhu.

Rosalia Scalia: You said that in the past you didn't know how to create sentences. For a writer whose sentences are lyrical and powerful, that is quite a leap. What did you do teach yourself how to write? Did you do imitations, study craft?

Amandeep Sandhu: I remember in my early twenties I often sat with blank pages unable to write a single line in English, or any other language for that matter. Before I began writing, I remained plagued by loss of coherent articulation, not only in writing but even otherwise. Stigmatized by the world owing to my mother's mental illness, having seen militancy up and close, being in the university environment where people made coherent hair-splitting debates on literary theory and gender/caste politics, many a time I lost my nerve and voice. Yet, you learn swimming by swimming, you learn driving by driving. Classes can't teach you that, they can only open your eyes. I did not have opportunities to learn from classes so I tried to open my eyes anyway.

How did you get from learning state to accomplished?

Thank you about what you say about my language, but tears really have no grammar, rage has no syntax. A heart weeps, it pours out on pages. The only method for me is to lay out my feeling and thoughts on paper, make them external to me and then play with them. Keep hammering them to shape themselves into a story. Notice in Sepia Leaves the subject is madness.

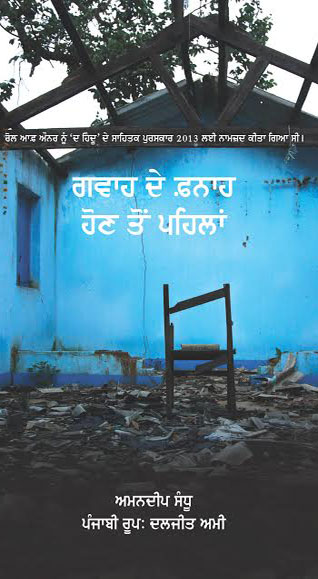

Now madness does not have a language. In fact, it is the lack of language that most characterizes it. In Roll of Honour the subject is militancy. Now militancy does not have a uniform narrative or absolute heroes. In fact, it is the lack of heroes and narrative that most characterizes it. So, there is effort in fathoming a thread that a reader can hold from beginning to end. Yet, in any art, the effort and the expression have to fuse for it to seem effortless. W. B. Yeats asked, “How can you tell the dancer from the dance?” Making stories effortless, stitching large parts of them together and ironing out small wrinkles is the effort. Sort of like the famous sari of Dhaka that can go through a finger ring. I ask myself why can't I take it through an eye of a needle. The reshaping teases out more stories from myself.

Tell me about process from getting from no language to language.

I kept reading great writers, somewhere subconsciously I learned to articulate my thoughts. I learned to say what I felt. Writing is not brain surgery. Mistakes are allowed. It never occurred to me to imitate great writers. I really did not know that was a possible technique. How can Steinbeck writing about Oklahoma give me language to write about Rourkela? In India, apart from a small minority which is now growing in numbers, no one emotes in English. To that extent all writing about inner India is actually a translation of language from native to English.

But, Steinbeck and probably only he, can show me the hearts of his characters from a once well off and now destitute family who are on this long journey where everything falls apart and finally they are deprived of even the fruits they themselves pluck. From him I can be inspired to show how my character's body is scalded in a furnace in a steel factory, how his heart is scalded by the unrest at home. That is what I did, with numerous writers. I learned how they showed hearts, not words or commas.

What authors influenced you most on this journey? Excerpts of Sepia Leaves that I’ve read echo Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird.

Just before I started writing Sepia Leaves I finished reading Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines. For many mornings I woke up with that book’s pages in front of my eyes. The models for Sepia Leaves were Jerzy Kosinski's The Painted Bird and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird.

For Roll of Honour the models were Kenzaburo Oe's Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids, Mario Vargas Llosa's The Time of The Hero, William Golding Lord of the Flies and Lorraine Hansberry's What Use Are Flowers? They were models in the sense that the subjects of these books were close to the subjects of my books, and these writers had pulled them off so wonderfully. I met most of these books while I was midway writing my stories. Perhaps if I had read them before writing, I may have decided not to write. They had said it all, said what I wanted to say, there was no need for me to say any more. I believe it is a function of writing to give readers language which, when a reader employs it, resounds better than what the reader would have him/herself uttered. These novels are also great because they take the reader deep into the situations and allow readers to find their way around. I wanted to achieve that quality in my writing. Come, empathize, and struggle a bit. It is okay to have problems but what is not okay is to not deal with them.

What brought you to literature in the first place?

I was crazy enough to do my Master's in English Literature from the University of Hyderabad. Crazy because the kind of larger family and background I came from, boys did not study literature. Boys joined the Army. I did not come from a so-called refined family, one that placed value on the Arts. In India, in the 90s, literature was an “impractical” course to study.

The country paid engineers and doctors, not school teachers or peons which is what I would have become if I had tried to get a job through my degree. I knew I was hopeless at competitive exams for civil servants. So, I was really crazy to study literature which I did because I knew no other way to address the angst in me but by reading and trying to understand how great writers had explored and written about the human condition.

Are you a comic book fan? Asking because I’m thinking of what Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy said in a radio interview I heard. He said, “If you’re looking for monsters, pick up the newspaper. If you’re looking for characters struggling to be human, pick up comic books.”

Comics and super-heroes give you hope that a savior can help you get out of your sticky situation. When at home, in my childhood, I day-dreamed Phantom, or Tintin, or Mandrake, or other Indian comic heroes will take me to a nice island or to Xanadu where like magic we will live happily like a family. There were so many super-heroes, I hoped one would come! The Indian ones are Badal, Chacha Chaudhry, Champak, Tinkle, Chandamama and so on.

As I grew older and the problems did not disappear by magic, I started reading works on what we call madness, and I realized they were great but mostly for their form and the content had become subservient to the form. Virginia Woolf invented Stream of Consciousness; Edward Albee developed Absurd Drama. Ken Kesey created Bromden in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

. In my view, it was excellent to have a pretending-to-be-deaf-and-mute character who is privy to the Combine, but in the movie Jack Nicholson as McMurphy steals the show. Same in many other works, so I decided I want to make a book which will take the reader closest to the small care-giving boy Appu who lives in the shadow of Schizophrenia.

Also, you said you began writing as a way to understand yourself and yourself in the world. How did you come to structure your books so that you are exploring yourself but also the world at large?

That is right. To me writing is about engaging with life. Writing has its more public facets: launches and readings and readers and fans, but to me it is more about it being a mode to inquire into one's own self or into one's society. The reception Sepia Leaves brought many readers calling up, writing in to say, “Thanks, you told a story about a situation which we have often experienced in our families but did not know could be a story.”

What I had done in the book was articulate, find words, for what mostly remains inarticulated: the helplessness in the face of overwhelming, messy, domestic problems springing from mental illness.

With Roll of Honour, the problem was with labels, with words. It’s a story of split loyalties of a Sikh boy in a boarding school during the Khalistan movement (years of militant separatism in Punjab). I realized mostly our loyalty is for labels: friend, nation, lover, and so on. We name something, and then find our ties with it. But here the words had split, hence the loyalties were split. That took me to a learning of the 'form' and the 'formless,' the word and the meaning, sagun and nirgun, and I found the meaning lay somewhere in between. I learned from Kumar Gandharv, who used to be an excellent singer in the 1950s - the prince of Indian music - and then he contracted tuberculosis and lost one lung. As he lay convalescing for over 15 years, unable and not allowed to sing, he heard beggars sing devotional songs by an iconoclast 15th Century poet, Bhagat Kabir. When Kumar was finally permitted by the doctors to sing, this master of classical music started singing those bhajans. The world of music was aghast but gradually started appreciating this kind of singing. When Kumar holds a note, it is held without the support of meaning - up in the air for all to marvel. That is the middle path between sagun and nirgun. It does not have words, but it makes sense.

Most good writing is held together by one underlying idea. It could be anything: love, death, migration, whatever. But there is always an idea. In my two books I chose to inquire into my two main thoughts/ feelings. In Sepia Leaves, it is guilt which I chose to answer from the question: Where do I come from? In Roll of Honour it is fear which I chose to answer from the question: Who am I? I also saw most good writing operating on two, if not more, levels: the text and the sub-text. Taking a cue from the chorus in Greek plays - some of the earliest well-formed writing - and the concept of the story-teller (sutradhar) in ancient Indian texts, I externalized the text and sub-text in my novels by employing two voices. Since the books are fiction but largely based on elements of autobiography, my voices are: one adult (which is the narrator) and one of the protagonist in the past (who is also the narrator of the period in which the story transpires).

What is it about Kapuscinski's work that spoke to you when you first read him? How does his work influence yours now? What do you admire most about him?

When I first read his book, I was a journalist, in the mid-90s. His book Imperium on the fall of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was just out. In this book and others, he writes in the interstices of the private and the public/ political, of the fact and the fiction/ fantasy.

His subject was us: third world, Africa, Latin America, and USSR, the ‘other.’ But he too was an ‘other', his nation behind the Iron Curtain - an oppressed society, othered (if you will) by the Western world and by the Soviet regime. We were both powerless, yet he helped me, and I hope all his other readers understand how political power operates in the larger world. He covered 27 revolutions, was given the death sentence four times, was imprisoned or detained countless times. I was a journalist. I hoped to have a bit of his life, but then I became a writer and let him inform my writing. Because of India's role in world affairs in the 1950/60s and the way India was developed along socialist lines, Imperium remains a favorite.

The next in my order of favorites is Travels with Herodotus, which is partly about India. Of course his most famous work is The Emperor.

Who are some writers you enjoy now? And why?

Ah! Too many, too many to count! The reason with each writer, say Chuck Palahniuk or Junot Diaz, is that the books are not writing. They are life. Yes, I recognize they have great craft too. I am a slow reader. I keep going back to some books and also explore newer writers but not the very current ones. I like to see which books stand the test of time.

What parts of the books were the most difficult to write? Why? What parts, your most favorite?

What was most difficult in the first book was choosing the title. In the second book, the first line was the most difficult to formulate. I haven't progressed much. A mother likes all her children, every single comma and full stop. I normally like the italicized (adult) parts more because they are my more recent expressions and emotions. I realize what is most important in a work of fiction or even other writing is: a) the voice that can earn the reader's trust, and b) the point of view, which can inspire confidence in the reader that the author can to tell the story.

Until now I have just prepared myself to learn these two; having finished some of my major autobiographical writing, it is now that I look forward to learning how to write. I love Italian writers Dario Fo and Luigi Pirandello! How did I forget? I would have not been me if they had not written! Now begins my journey, like the red ants. I travel states and write about migration, learn why it happens, how to write about it. It is a very long journey.

Readers can learn more about Amandeep Singh Sandhu at www.amandeepsandhu.com.

December 8, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: Meenu Mehrotra (Dubai, UAE), December 08, 2011, 4:45 PM.

Awesome, Aman. Many congratulations and loads of luck.

2: Bulbul Mankani (India), December 09, 2011, 7:11 AM.

"Sepia Leaves" is both stirring and authentic. Amandeep writes with both heart and soul. To unmask his self in a first novel is also very brave. What moved me most about the book was the kind of distant, dry-eyed look he takes at what must have been confusing, complex and excruciating memories ... I should know ... I have a bipolar mother.

3: Kulvir (India), December 09, 2011, 1:18 PM.

Eagerly waiting for the 'Roll of Honour' to roll out on the book shelves.

4: Lindsay (Bombay, India), December 16, 2011, 5:22 AM.

I look forward to reading "Roll of Honour", Aman. Much luck.

5: Edith Parzefall (Nuremberg, Germany), December 16, 2011, 6:21 AM.

Fascinating interview, Aman. I hope the red ants will show you the way for a ticket to Canada. As an admirer of "Sepia Leaves", I'm happy to hear "Roll of Honour" will be released next year. Congratulations!

6: Probal Dasgupta (Kolkata, India), December 20, 2011, 12:46 PM.

A great take on yourself, on life, on reading, Aman. "Roll of Honour" will, I'm sure, be very different from "Sepia Leaves". Can't wait to read it. Wonder if your attitude to reality will mutate to the point of your wanting to write fantasy at some stage - you mention liking Tolkien. Try Paolini, if you haven't already.

7: Asit Pant (HImalayas), December 24, 2011, 2:10 AM.

The power of Aman's work, to me, is in the fine balance between the intricacies and emotions of the events, and the "affectionate detachment" of the narrative. Only someone who has gone through quite a lot and managed to analyze it, make sense of it, and even perhaps been thankful for it, can write this way. I guess he treads the two worlds of "sagun" and "Nirgun" - consciousness and form - that he speaks of. And, perhaps, he is both the red ants and the car in which they travel - the driver and the driven. One of the reasons `Sepia Leaves` touched me was because of the almost anthropological observation and note-taking which envelopes the beautiful depiction of mental illness and its sombre effects on a family. And, on another plane, there is pain, but there is dignity as well; there is desperation, but faith lurks around somewhere. Beyond the darkened curtains, the sun waits. I once read the transcript of an interview Aman did with Habib Tanvir, the famous playwright and theatre director. In one question that had just three words, Aman managed to draw out from Mr. Tanvir the essence of Charandas Chor, the protagonist of the play. This discussion does the same in a way - it beings out the "making of Amandeep Sandhu, the writer", wrapped in the HTML tags of a single page. Kudos and thank you, Rosalia, for bringing this to us.