Art

The Artistic Face Of Modern Britain:

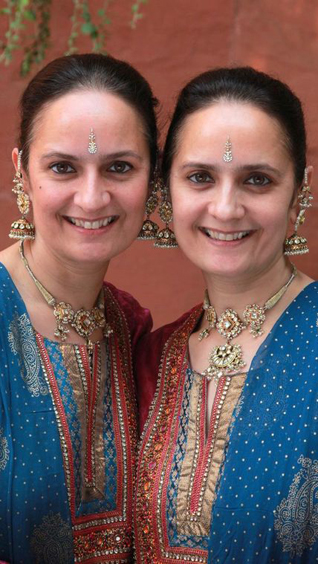

The Singh Twins

CAROL MIDGLEY

The Singh Twins don’t mind if you confuse them with one another. In some ways they prefer it if you don’t distinguish between them at all.

Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh are the identical Sikh sisters who grew up on the Wirral (United Kingdom) and whose art fuses the subcontinent’s miniature tradition with contemporary western influences to create a unique, rich genre.

Simon Schama recently cited them as the artistic face of modern Britain, and his new series on the historical portrait finishes in the present day by looking at their art.

The Singh Twins, who will be 50 next year, work together as a pair but present themselves as one artist.

“We generally don’t like people using our individual names anyway because . . . in our work as artists we are the Singh Twins; that’s our professional identity,” says Amrit when I meet her and Rabindra in their large, detached house near Birkenhead on the Wirral, where they live together with their father and other members of the extended family.

With friends and family, things are obviously different, but when it comes to their art they are a single unit. They dress identically -- right down to their dresses, earrings, bracelets and the bindis on their foreheads -- and do so even when they are alone and a photographer isn’t here to take their picture.

They have only ever spent two weeks apart, once because one of them was in hospital and another occasion when one had to do jury service. They often finish each other’s sentences, share the one mobile phone and a yellow two-seater BMW sports car. They sound very alike on a digital recorder too. So you don’t mind if I accidentally attribute a quote to the wrong sister, then?

“I’d love it if you could [just] say ‘the twins’,” says Amrit. “I know some don’t like being ‘the twins’ but because it’s so ingrained as our professional identity it’s actually what we prefer.”

There is a good reason for this and it was an early driving force in their work. When they were at art college in Chester and trying to promote their own style, which they call “past modern” -- using the ancient Punjabi and Indian traditions of their heritage but in a vibrant, contemporary way to tell stories and make political statements about the world now -- their tutors were dismissive and told them it was “backward and outdated” and had “no place in contemporary western art”. Self-expression and individualism were, they were taught, key.

Their mission from that moment was to prove their tutors wrong but also to challenge and subvert the concept of “individualism” (in Sikh philosophy, community comes before self) and identity.

They began dressing alike (they hadn’t done so before), calling themselves “twindividuals”, and posing the question -- what’s wrong with being the same anyway when much of the “individualism” promoted by the advertising and fashion industries is an illusion (selling millions of people the same skinny jeans)? They argue that their sameness is their individuality: “Our twinness sets us apart from other people and that’s what makes us unique.”

They experienced years of being pigeonholed by the mainstream galleries, receiving letters saying things like: “We love your work but have you tried the ethnic gallery in your area?” This even though they were born and brought up in the UK (they describe themselves as contemporary British artists) and their work is fabulously fresh and modern, in some cases almost like pop art, addressing subjects as varied as the Beckhams, Geri Halliwell, football, Blair and Bush, and containing wit and little hidden messages.

They often strive to show the interconnectedness between east and west (“we are not as separate as we think”). Now they are internationally acclaimed award-winners who received MBEs for services to art and are championed by Schama as artists whose riotous, intricate, diverse work -- in titles such as ‘Painting the Town Red‘, featuring Liverpool football fans, Liverpool’s waterfront, Afro-Caribbean, Chinese and Asian people including their own aunt and uncle and cousins -- as celebrations of the fact that there is no one face of Britain.

Do such tributes signal that they have now been embraced by the “establishment”?

“It’s brilliant for us; it’s a vindication of all we have been working for as artists since day one . . . trying through our work to get people to view culture and identity in new ways and . . . be more inclusive,” says Rabindra (I think it’s Rabindra, anyway) of Schama’s words.

The mindset, both sisters feel, has changed since the 1980s when they were students. “But I still feel there is a glass ceiling within the contemporary art world,” says Amrit. “I’m not sure whether the Turner prize or the Venice Biennale would still look upon our work as . . . representing what is of Britain now. But we’ve never really been about that anyway . . . [we are about] reaching out to the masses.”

Many of their works also reference the “dilemma” often projected on to Asian people who were born here and that they see as a non-issue; the twins have often been asked “Which one are you -- British or Indian?” as if they have to choose. They say the answer is both; they take the best from both worlds, they are fiercely proud of Liverpool and Britain but equally celebrate their Sikh-Punjabi heritage. Most people hail from different places, they say. “You might as well say ‘Are you British or are you Viking?’ ”

Indeed, Schama has said of them: “The British response one finds in the Singh Twins’ work is not a soppy, sentimental paradigm, it’s one that has just a few notes of optimism. They do actually think of themselves as Liverpudlians, and as Liverpool Sikhs.”

Their father first came to London in 1948 as a child with his family, following the Partition of Punjab and India. The twins were born in 1966 and when they were eight their father, now a retired General Practioner, moved the family to the Wirral for his work. They were educated by nuns at a Catholic convent school, the only Sikh-Britons or of Indians origin and only non-Catholics on the register.

Initially they intended to study medicine but say the school stymied their applications, believing they were driven to medicine only by “parental persuasion and family tradition” (the stereotype then being that Asian parents were pushing their children into becoming doctors). Now they recognise that fate played a hand in directing them towards art. But the school did feed their interest in religious iconography, and among the items in their house is a huge Virgin Mary statue along with various Sikh religious artefacts.

Both twins are single and have said that they spend 99 per cent of their time together -- so do they think it would have interrupted their creative flow had one or both of them been married? “I think it’s bound to change the dynamics isn’t it, not just having somebody else there but also having other commitments [such as] other families and children,” Amrit says. “Being an artist is a very difficult thing to do if you have a family, particularly with the kind of work we do where you are having to sit for hours on end and planning your work and creating your work.”

Indeed, when painting they can sometimes work from 9 am to 2 am the following morning; it can take four hours to complete an area the size of a postage stamp. “We are very active in our family home anyway,” she continues. “Part of being in an extended family is that we have responsibilities that we have to deal with in household, [though] it’s not quite the same as having your own children and that level of commitment.”

They do believe, however, that being female probably made it easier for them to become artists. Their family always supported them wholeheartedly but: “I’m wondering if we were men whether more pressure would have been put on us to get a ‘sensible’ job because you’ve got to bring up a family.”

I ask what would be their “Desert Island” work, the one they’d most hate to be without. They choose their portrait of a dear, late uncle who always championed their work and kept their spirits up amid the more difficult years, and ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four‘, one of their most well-known paintings, which depicts the storming of the Golden Temple in Amritsar by Indian troops ordered in by Indira Gandhi in 1984 that left thousands of innocent men, women and children dead.

In November Tate Britain will borrow one of their works, enTWINed, from the Museum of London to feature in an exhibition entitled ‘Artist and Empire.’ This adds to an impressive list of galleries in which they have exhibited, including the Walker Art Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow.

In 2011 they became the only British artists, aside from Henry Moore, to have been offered a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern Art, in Delhi.

Despite their tutors initially dismissing the Indian miniature tradition as passé, the twins’ success has ultimately proved their own instincts right. “It’s about valuing tradition in the modern world,” Amrit says. “We stick with that style because we are trying to provoke the art world into accepting other art forms. Modernity travels with tradition.” It is also a modern lesson in the value of sticking to your guns.

The Face of Britain by Simon Schama begins on BBC Two on September 30. ‘Artist and Empire’ is at Tate Britain, London SW1, from November 25, 2015. For more information, Please CLICK here.

[Courtesy: The Times. Edited for sikhchic.com]

September 20, 2015