Art

Punjabi Aesthetics in The Art of Arpana Caur

QUDDUS MIRZA

Many years ago, a self-proclaimed intellectual used to roam the studios of NCA in the late afternoon. Coarse cotton shawl wrapped around his shoulders and surrounded by ‘disciples’, he went from one space to the next in his search to locate the true expression of Punjabi painting.

According to him, no one was able to formulate a ‘Punjabi visual vocabulary’ since Amrita Sher-Gil. Occasionally, he spotted some mustard fields rendered expressionistically in a student’s work, and was elated to discover the great genius of indigenous aesthetics.

But the said student, who was suddenly elevated to the profound practitioner of Punjabi painting, was not aware of this aspect of his academic exercises. Much like his fellow students, he was only trying to depict reality from surroundings as honestly as possible. But the intellectual insisted on seeing art through a particular angle, no matter how limited and superficial it was.

That was a story from a bygone era, an age of innocence, prior to the present times of information excess. Today, the same intellectual would be able to open the internet and navigate through images by numerous artists who are trying to create a work, without being conscious of it, that can be classified as Punjabi art.

More than the lack of internet facility, the intellectual was oblivious or ignorant of Punjab that lies beyond borders -- in India. The creative individuals from Indian Punjab are producing great works in the realm of poetry, fiction, music, dance and visual arts. One example is the works of Indian Punjabi painters, such as Manjeet Singh Bawa, Premjeet Singh, Arpita Singh, Arpana Caur and many others.

Recently, a monograph on Arpana Caur has been published which brings forth critical insights and responses to the work of a Punjabi painter known for her distinctive, personal and poetic imagery.

‘Arpana Caur: Abstract Figuration’ is a collections of essays by some of the leading writers and critics of Indian art, such as Yashodhara Dalmia, Gayatri Sinha, Uma Nair, Georgina Maddox, Robina Karode and Rajiv Mehrotra. Many international authors, like John. H. Bowles, Nima Poova-Smith and Ernst. W. Koelnsperger, have also contributed to the monograph.

All these texts are attempts to contextualise and analyse the art of Arpana Caur, which is deeply rooted in the traditional narrative structure of Punjabi and Indian aesthetics.

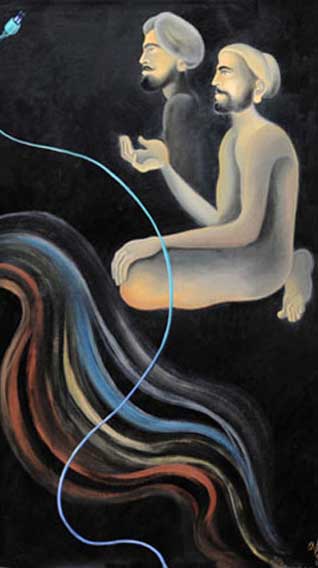

Looking at her work reproduced in the volume (published by the Academy of Fine Arts and Literature, New Delhi), one discovers the link that exists and binds her work from different periods. The construction of space, placement of figures and rendering of different characters reveal a unique way of looking at the world.

But, on a deeper investigation, the uniqueness of her imagery seems closer to folk tales and popular Punjabi poetry. Flights of fantasy that characterise those verses have a parallel in the canvases by Arpana Caur -- a stream emerges from the chest of an old man, a large foot is composed of a sage and trees, or a woman includes heads of men inside her body.

Along with these excursions in imagination, several other canvases confirm how the artist takes liberty with the known world and manipulates and reorganises its ingredients to fabricate a narrative that suggests situation rather than a scenario. For example, in the ‘Tree of Suffering, Tree of Enlightenment’ an ordinary man’s lower half becomes Buddha’s torso -- an uncommon combination that indicates multiple conditions of man.

This aspect of suffering appears frequently in her paintings but Arpana Caur has adapted the visual of a female as her main symbol to portray that condition. In many works, the woman is sliced, chopped and dismembered -- mostly with a large pair of scissors and measuring tape.

Contrary to general or quick assumptions, her work cannot be confined to the category of feminism. Replying to Yashodhara Dalmia’s question: “Would you call yourself a feminist?” in her book, Arpana Caur replies: “No. Because the themes are more wide ranging. Time was my predominant theme always from the 70s. And time is not confined to a woman’s way of thinking but it’s a phenomenon that every human being confronts, like day and night, life and death. These have been my favourite themes.”

Fascination with time is apparent in her other works, too, which are created for the book ‘The Man Who Always Wore a Watch’, written and illustrated by her (and included in the monograph). With clocks, pair of scissors, flames, fires and flowers she has constructed a narrative in which one enters as easily as one accesses a piece of poetry from the soil of Punjab.

This connection (perhaps evolved without a conscious effort but due to the artist’s genuine interest in the aesthetics of her region) helps her to transcend her boundaries and makes her an important artist of our time and place -- on the both sides of the border.

[Courtesy: The News on Sunday. Edited for sikhchic.com]

December 30, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Harinder Singh 1469 (New Delhi, India), December 30, 2013, 2:33 PM.

She's simple. Humble. Gentle. Hardworking. Soft. Musical. And utmost respect for her elders. Her work has a lot of depth in terms of shapes and history ... wish we could buy more of her stuff. Our very best wishes for her new ventures on phulkari work for the women in the Punjab rural sector.