Art

My Mother The Archivist:

Nony Singh

SOMAK GHOSHAL

In 1948, when she was 12 and attending boarding school in Dehradun, Ranjit ‘Nony’ Kaur Singh would spend all her pocket money, the princely sum of Rs.20 she got every month, on Kodak films for her box camera.

The year before, her life had suddenly changed one day when she was forced to flee her hometown Lahore with her family in the wake of the violence that broke out during the Partition of the subcontinent. But amid all the tumult, photography had been, and was to remain, the one constant in her life.

“I was 7 when I took my first photograph,” says Nony, now in her late 70s and a resident of New Delhi for many years. It was a portrait of her mother, Mohinder Kaur, sitting in a clearing, seemingly lost in her chores during a family picnic near Rawalpindi, Punjab -- now in Pakistan.

A strikingly accomplished composition, it captures the essence of its subject -- “graceful, dignified and wise,” in Nony’s words -- with a quiet confidence.

Four years later, Nony would go on to make another portrait of her mother, a more self-consciously stylized one this time, by making her pose on the roof of their house, dressed in her other parent’s clothes, holding a policeman’s baton, and wearing a mighty moustache.

While the two photographs could not be more different in their appeal and approach, one thing is common to them. They are not simply pictures of a person, but fully realized portraits of an individual, offering the viewer glimpses of an essential truth about the sitter while also conveying a sense of the curiously inventive eye behind the camera.

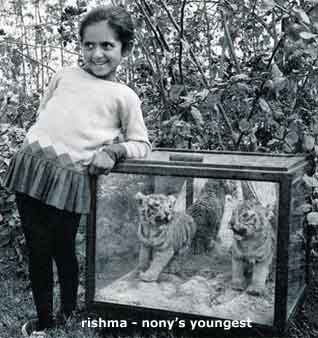

Over the years, Nony would go on to take thousands of photographs of her friends and family, especially of her four daughters, collecting negatives and albums in an ever growing archive.

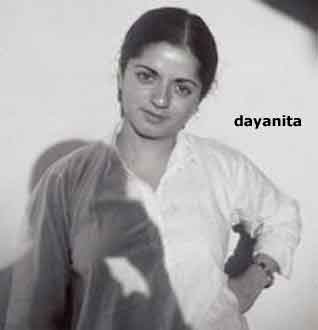

A handful from that sea of images has now been selected and curated by Nony’s first-born, Dayanita Singh, one of the country’s finest photographers, artists and bookmakers.

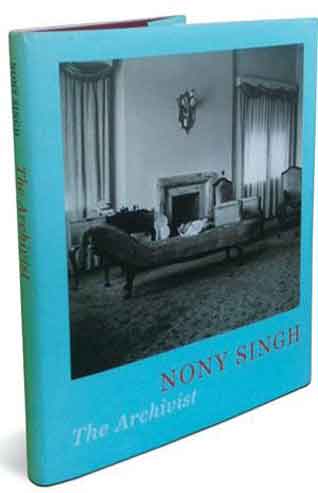

“Nony Singh: The Archivist is a companion volume to my book Privacy (2004),” says Dayanita, “You can see how influenced my portraits were by her aesthetic.”

The books look like identical twins -- with teal-coloured covers, exquisite typography, and photographs of gem-like clarity. Nony’s book comes with texts by Sabina Gadihoke and Aveek Sen, providing a historical and autobiographical context to the work.

There is also a note by Dayanita, culled from Privacy, which acts, retrospectively, as a gloss on the affinities between the books and their authors.

“I was the most photographed child in my family,” writes Dayanita in Privacy, and the evidence is ubiquitous in her mother’s archive.

From the photograph of baby Dayanita, nicknamed Nixi, lying on a chaise lounge in a hotel suite, to portraits of her as a little girl in fancy dress, some of these images have been seen before, most memorably in one of the seven accordion-fold volumes (“Nony Singh”) that make up Dayanita’s 2008 work, Sent a Letter.

In 2007, mother and daughter had been shown together in an exhibition, Nony and Nixi, in Arles, France. But Nony Singh: The Archivist reinvents these familiar images by placing them in relation to other sets of photographs and creating a narrative arc that is at once tender, ironic and filled with a sublime mystery.

A photograph of Nixi from 1961, the year she was born, on her grandmother’s lap is followed by one from 2013, showing the artist with her head on the lap of Mona Ahmed, the subject of one of her early books and now a dear friend.

Although set only a few centimetres apart, the photographs have more than half a century of history -- of disruptions, departures and discoveries -- between them. On their own, each is a testimony to a singular moment of intimacy, frozen out of time; but in relation to one another, they suggest the continuity of a certain kind of emotional bond.

Perhaps the most arresting image in the book is of Dayanita as a young woman, impatient to leave home for college but stopped by Nony for one last photograph, over which the mother-capturer’s shadow is imprinted.

In spite of their elegiac gestures, reflections on mortality and being chronicles of human fragility, Nony’s photographs are informed by a robust imagination, keen to push the limits of the real, and harvest the possibilities of fiction. The book begins with a series of photos of her husband, with dozens of his ex-girlfriends, discovered by Nony one day in a trunk.

“I was angry because photographs are such precious things,” she tells Gadihoke. “I said to him, ‘Even ex-girlfriends deserve some respect.’” So she pasted them in an album and added her own photo with her husband at the end with the inscription: “Girl friends till he married Nony, Hope so ... Have some respect for photography at least!”

Clearly, photographs occupied a special place in her mind all along.

Early in the book, Nony tells us the story of a little girl who “enjoyed being behind a box-camera” and how she grows up and goes on to create her own “camera family”. The passage is like a fine photograph in prose -- succinct, precise, and filled with silences and elisions that tease the eye and mind into thought.

Growing up in the shadow of the war, Nony remembers going to school in the middle of curfew -- her father, a policeman, had a curfew pass, and would not have his children’s education interrupted even by fire and riots.

“I had a recurring dream of Hitler when I was young,” she says. “He would land on our roof in an aircraft and I would be begging him to go away and come back a year later.”

The dramatic potentials of her sensibility were kindled by her love for the cinema. A huge fan of Nargis, Madhubala, Meena Kumari and Nimmi, young Nony would dress up as her favourite heroines and strike a pose, or have her sisters emulate a Scarlet O’Hara look, before the camera. Later, she also took great pleasure in transforming her children, especially her eldest daughter, into imagined characters: one of the most delightful sequences in the book is of little Nixi in various guises.

“She dressed me as a Romanian gypsy and took a photograph,” writes Dayanita in Privacy, “it turned out to be quite prophetic.” She adds: “I am glad that I did not settle into the role of her portrait of me as Mother Mary.”

For many years after her husband died, Nony was embroiled in endless litigation over property, which left her with little time or spirit for photography. Impressed by her unshaken will, people in the courts would call her a “man”; while driving home to her little children late in the evening, she would disguise herself by wearing her husband’s last tied turban. Now mostly confined to the house, Nony is working on her next book of photographs, made of television screenshots.

Nony Singh: The Archivist releases on 29 September and will be available at the Delhi Photo Festival 2013 at a special price of Rs.1,200.

[Courtesy: The Wall Street Journal. Edited for sikhchic.com]

September 28, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ), September 28, 2013, 6:15 PM.

Nony ji, this could have been my own story, except that I didn't have the luxury of an allowance of Rs.20. My first camera was a Kodak Box that cost Rs 6 and 12 annas. I was 12 or 13 years old then. I attached myself to one 'Lat Studio' as an unpaid apprentice in Lyallpur. Soon, I was handling the developing, printing and enlarging. At the age of 14, I had the first taste of success. One of my photographs was accepted for the Kodak Magazine published from Bombay. I went on to win some 15 - 20 first prizes, and even started a photo studio as well. But couldn't sustain it as a profession for a simple reason: I wouldn't charge any money from my friends. I had to leave and eventually set roots in Malaya as a planter. My friends always took credit for the eventual successful career while I still nurtured my first love and had my work published in reputable magazines like Punch, Sphere and Far Eastern Review. It is a long story. Thanks, once again, Nony ji, for evoking those nostalgic memories.

2: Harinder Singh 1469 (New Delhi, India), September 28, 2013, 10:59 PM.

Yes, we did attend the Delhi Photo Festival 2013. It was very well organized. A lot of energy in the show as we could see a good number of people from all over India. Also, we could see over 2 dozen pictures by Dayanita on the screen. Lesson we learned ... that one must encourage the new generation to develop interest on their parents or elders' good work. You never know, this can lead to big success -- specially when it comes to cashing it ... as youngsters may use better resources and take things to new heights, influence with technology, etc. Big thanks to sikhchic.com for making us read such wonderful columns - which are unlike anything else and different and not run of the mill. Thanks ... thanks ...

3: Inderjit Singh (Chandigarh, Punjab), September 29, 2013, 5:08 PM.

I was the straw that broke the camel's back. Among other photographs, it was my life size portrait that Sangat produced for which he would charge me nothing, nor would he change his mind ... which peeved his partner in the studio. It was in 1954 when he packed up and landed in Singapore. In 1957 he landed himself in Malaya in a prestigious job as a Planter with the world's largest plantation company, Guthrie & Co. There was no looking back and he touched the sky even in that profession. He continues with his first love, Photography, now, as a hobby and has gone on to win a handful of first prizes when his work appeared in a number of international magazines. I rightly take credit for triggering his talent.

4: Satpal Singh (Kuala Lumpur), October 03, 2013, 12:03 PM.

Ah, Uncles Inderjit and Sangat! The banter enters a different dimension: the commentary box even!