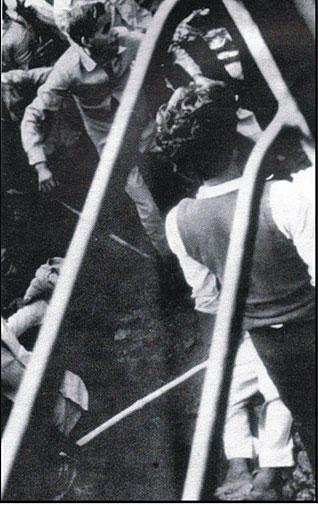

Below, 3rd from bottom - A mob attacks a train and pulls out Sikh passengers from it. 2nd: An innocent Sikh is beaten, doused with kerosene, and set on fire. 1st: Only ashes are left from a lynching on a Delhi street. Thumbnail: Disinterested onlookers!

1984

Punjab - A Cataclysmic Showdown:

Aftermath and Challenges

A Book Review by NORMAN G. BARRIER

Punjab - A Cataclysmic Showdown: Aftermath and Challenges, by Bhupinder Singh Mahal. Singh Brothers, Amritsar, 2009. ISBN: 8172054173. 192 pages. Price: $22.00.

Scholars often write books and articles on the experience of Sikhs in the diaspora. What often missed is the personal experience and perceptions of individual Sikhs active in professions and cultural life of their community.

This set of essays helps balance our understanding of how informed Sikhs view their traditions and daily lives.

Bhupinder Singh Mahal has played an important role in fostering multiculturalism in Canada, as well as providing leadership for health care in Ontario. He also has served as a Chairperson of an independent administrative tribunal that provides impartial quasi-judicial hearings on employment insurance decisions. His leadership in Canadian cultural life has been recognized by numerous awards and medals.

After decades of writing for Sikh journals and magazines across the globe, he has assembled a coherent perspective on Sikhism and the Sikh community. The essays cover a variety of topics, but several key themes run through the narrative: Sikh identity, experiences in the diaspora, Sikh history, and the role of modern communications in framing Sikh self-perception and the perceptions of those around them.

The initial chapter deals with the most important events recently affecting Sikhs in the Punjab, India, and the broader diaspora - the 1984 attack on the Golden Temple and the systematic massacre of Sikhs in Delhi. 1984 remains imbedded in the memory and daily lives of Sikhs everywhere, influencing most dimensions of contemporary Sikh discourse and public activities.

There have been many firsthand accounts, analytic studies, and polemic works written on specifics and the major issues involved in the violence and aftermath, including recent seminars and conferences. All Sikhs and their many friends and associates feel strongly about what happened, but there is significant division about details and the implications of both the attacks and the motivations of leaders, both Sikh and Congress.

Bhupinder Singh adds to the literature with a provocative synthesis of material that combines a brief history of Sikh revival since the Singh Sabha period (c. 1870s-1920s) with sharp criticism of Indira Gandhi and attention to the role of the press, the neo-Hindu role in the massacre of Sikhs, and the failure of accountability for those who planned and carried out atrocities.

One can argue with details in the narrative, but taken as a whole, the assessment represents clearly how one Sikh, and by extension, many Sikhs, view the past events. Especially useful are sections on the failure of the press to cover events accurately and the need for justice, so that Sikhs and India as a whole can move forward from the tragic events.

The second chapter, "Campaign to Recast Sikh Image by Sikhs of Diaspora," focuses on controversy over Sikh tradition and identity. The overview reflects the author's personal experiences, as well as a particular understanding of Sikh history and traditions.

He argues that despite the lack of clarity in defining "Who is a Sikh" in two pivotal documents, the 1925 Sikh Gurdwara Act, and the Sikh Rehat Maryada promulgated by the SGPC and now widely accepted by many Sikhs as a definitive guide to Sikh ritual and daily life, most Sikhs had little concern over definitions and the traditional roots of their religion until W.H. McLeod's scholarship raised divisive questions in the 1980s.

While the argument makes sense to some Sikhs, the historical record suggests a far more complex story that has its roots within the Singh Sabha movement itself, an intense debate over the centrality of the Khalsa and Amritdharis and the implications of any resolution of the contentious issues for political survival.

This has been explored in numerous chapters, essays, conference proceedings, and most clearly, in McLeod's study and translation of the historical rehatnamas, Sikhs of the Khalsa. The most useful part of the essay reviews contemporary arguments among Sikhs and scholars on the same issues.

As a founding member of the Sikh Diaspora discussion group, Bhupinder Singh had a firsthand view and personal experiences with the heated debate in cyberspace over "Who is a Sikh" and the centrality of Amritdharis in Sikh tradition and institutions. There were literally hundreds of detailed messages passed back and forth in the ongoing discussion.

Bhupinder knows only too well the frustrations and inner workings of the site, leaving a fully understandable bitterness about the fairness of communications and the attempt of Sikhs, often non-Keshdhari, to question claims about who really are Sikhs and who should control public space.

The arguments persist and will continue, in new forums such as the influential Gurmat Learning Zone and sikhchic.com.

The next three chapters are useful in understanding the problems confronting Sikhism in a global context.

"Cross-Cultural Influences and Doctrinaire Ambiguities Bedevil the Sikhs" explores how living in a multicultural milieu beyond Punjab affects perceptions of Sikhs and, most important, Sikh attempts to adapt their daily lives and traditions.

He discusses the sharing of festivals and Punjabi traditions such as Sikh women observing Karva Chauth, often associated with married Hindu women fasting to secure the longevity of their husbands. Balancing distinctively Sikh observances with overall Punjabi social events or anniversaries often becomes a focus for intense debate over identity.

One might also mention how Sikh observance of Diwali each year predictably creates a storm of contesting messages on the internet and in Sikh institutions.

Bhupinder Singh examines how Sikhs, and Hindus and Muslims, confront reconciling practices and symbols within a foreign context. The turban and kirpan obviously come to mind, especially after 9/11. These themes also are explored in a separate essay later in the volume.

He raises a central question for Sikhs in the diaspora. Who speaks for the Sikhs and who decides controversial issues? The value and potential danger of having one source, such as the SGPC or the Akal Takht, reach decisions on appropriate action and matters of faith receive thoughtful attention, as summarized by the following :

"The community finds itself in a catch-22 situation. On the one hand, there is recognition that practices and observations that do not cohere with commonly accepted religious principles cannot be left unaddressed. On the other hand, although there is a growing consensus on standardizing of rites and observances, there is no clear agreement on whom to confer the power."

If I were to suggest one essay to give non-Sikhs who are trying to understand Sikh problems and feelings about themselves and their new environment, this would be the one, along with the collected works of I.J. Singh.

The other two chapters deal with specific representations of Sikhs and community reaction.

One focuses on misconstruction of Sikh history by V.S. Naipaul. Naipaul's questionable interpretations of Sikh history and especially events surrounding 1984 are examined, as are his sources of information.

Gurtej Singh receives special treatment as an influence on the author. The latter uses the discussion as an opportunity once again to explore the role of Bhindranwale and other Sikh leaders in the spiral of communalism and terrorism leading to the government attack on the Golden Temple and its aftermath.

There is understandable surprise that a world-renowned interpreter of Indian culture such as Naipaul could have missed the mark so widely.

I was reminded of what Khushwant Singh once told me.

"After hosting Naipaul and showing him the many wonders of Indian culture, all he remembered from the experiences was the large amounts of feces everywhere."

The second, "Attacking the Iconography of the Sikh Faith," reviews one event that both upset Sikhs and mobilized strong public opinion and action.

In December 2004, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre showed a controversial play by an aspiring Sikh playwright, Behzti (Dishonour). The play reolves around a sexual assault on a woman in a gurdwara, where cries of anguish are hidden by recital of the congregational Ardaas. Also involved were themes such as homosexual orientation and corporate responsibility.

Prior to the public performance, there had been attempts to modify or postpone enactment, as well as warnings about the inevitable Sikh reaction.

Bhupinder Singh analyzes the play and the resulting rioting, violence and contesting opinions. The arguments and issues are clearly demarcated.

What perhaps could have been explored was the divergence of Sikh opinion and concern with public perception of Sikhs as violent. The Sikh discussion group interchanges are rich in detail and throw much light on conflicting approaches to Sikhs in how to represent themselves in public arenas. As a case study, however, this is informative and generally accurate. Perhaps its inclusion in the volume will spark essays on other cultural representations of Sikhs, in films, BBC series, and documentaries.

The concluding essay, "In the Name of Whose God," explores Sikh perceptions of science, the nature of God revelation and worship. Emphasis is placed on the universal themes within Sikhism and its often successful adaptation in a non-Punjab cultural context. Implications for thwarting terrorism and encouraging intercommunity dialogue also are highlighted.

I personally disagree with some of the interpretations and general observations in this volume, but I recommend the writings of Bhupinder Singh Mahal as a highly useful representation of how Sikhs in the diaspora view themselves and their surroundings. Libraries should have copies, and those interested in modern Sikhism will find it a significant contribution to the literature.

We need more autobiographies, narratives and histories of local institutions written from an insider perspective. Different voices and experiences must be taken into consideration, if the ongoing saga of Sikhism in the modern world can be understood.

Prof. N.G. Barrier is based in Columbia, Missouri, U.S.A.

June 16, 2009