1984

Labh:

A Tale Of Resistance To India’s State Terror -

Part I

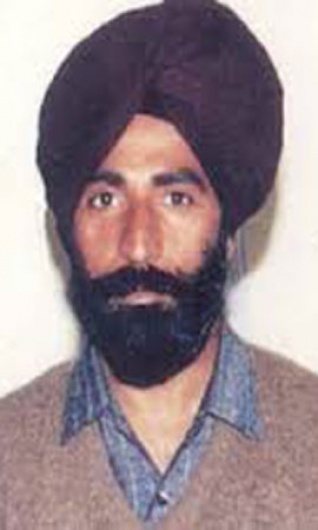

RATTANAMOL SINGH

The facts of 1984 and the tumultuous decade of state terror that followed, have been intentionally muddied and obfuscated by the Indian Government’s self-serving white-washes, and by a subservient and pliant media.

We present the following version of one chapter from the era, by one writer and researcher in an attempt to open a free dialogue on that tragic period, with the hope that by removing the onion-layers of censorship and misinformation, we may get, at the very least, a glimmer of the truth. [EDITOR]

Police said that 12 to 15 Sikhs -- most wearing police uniforms -- walked into a branch of the Punjab National Bank in Ludhiana, about 60 miles northwest of Chandigarh, shortly after it opened.

Mistaking them for real officers, bank employees shook hands with the robbers. Two security guards complied with requests to hand over their weapons for inspection.

The extremists, armed with rifles and submachine guns, then took keys to the safe from the manager and a cashier and locked the bank employees in a room, the spokesman said.

The Sikhs fled in a van after filling sacks with 58 million rupees -- $4.5 million. Part of the money belonged to the Reserve Bank of India, the country's central bank, which does not have a branch in the city.

Police said the robbers shouted slogans supporting Khalistan. Bank employees told the Press Trust of India news agency that the robbers said they would use the loot to buy arms.

Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1987

One month before the Punjab National Bank was robbed, Devinder Kaur sat in her house as her husband’s cousin, Paramjit, arrived. Paramjit gave Devinder a set of hasty instructions: “Take your father and son, get on a bus to Ludhiana, get off at the bypass, walk to the safe house, and wait.”

A few days later, the family followed Paramjit’s instructions and waited at the safe house outside of Ludhiana. Eventually, a rickshaw pulled up outside, and two men emerged. The first was Devinder’s husband, General Labh Singh. He was tall, thin, and wore a turban.

Three years had passed since Labh Singh and Devinder Kaur parted ways during the Battle of Amritsar. Only a year ago, with the Labh Singh on trial for the death of a newspaper editor, the Khalistan Commando Force launched a daring attack on the courthouse and lifted him from police custody in a sea of gunfire.

After his escape, Labh Singh and Devinder Kaur met only a few times in short, clandestine meetings facilitated by the General’s roving motorcycle soldiers and held in safe houses throughout Punjab.

The second occupant was Harjinder Singh Jinda, introduced to Devinder by the false name Vicky. He looked a lot younger than Labh Singh and walked into the house with a set of black sunglasses and an air of charisma.

A day would come when both Labh Singh and Harjinder Singh Jinda would enter the popular chronicles of Punjabi history. In the years to come, their memories would be musically imprinted into the Punjabi collective memory by Dhaadhis, the traveling bards of the Sikhs. The dhaadhis would travel village to village telling tales of the lives these two lived and the evil lives these two took.

For now, though, the resistance movement’s target was the Punjab National Bank in Ludhiana, and its members were converging on the city.

Labh Singh, his family, and the Rayban clad young man left the home to join them.

There was promise in this moment.

There was an insurgency to fund, weapons to buy, alliances to forge and, assassinations to plan.

A great game of nations, armies and ideologies was being played out in the Punjab, and the riders of this rickshaw hurtling towards Ludhiana represented perhaps the state’s best chance for independence.

* * * * *

The Punjab National Bank was robbed in the middle of a decade-long Sikh insurgency in Punjab. The Sikhs had a contentious relationship with the Indian nation-state since the country’s creation in 1947. Pre-Partition glimmers of self-rule quickly faded as the promises of partial autonomy made to the Sikhs were abandoned once India was constructed. In the 1950s, Sikh groups launched the Punjabi Suba Struggle, a large protest movement demanding a majority Punjabi speaking state -- to conform to the format already used to form other linguistic states.

In the 1970s, there were calls for greater autonomy and states’ rights following Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s suspension of democratic rule and unilaterally assuming dictatorial powers. By June 1984, the Indian Army had surrounded the Sikh forces at their spiritual center, Darbar Sahib. The ensuing Battle of Amritsar was followed by the declaration of Sikh independence in 1986 and open revolt in Punjab as the Indian military apparatus faced bands of Sikh insurgents.

One of these groups was the Khalistan Commando Force led by Sukhdev Singh, most popularly known as General Labh Singh. The first Act of this saga is an exploration of the 1980’s Sikh resistance movement aiming for independence from oppression, through the eyes of General Labh Singh’s wife, Devinder Kaur.

* * * * *

ACT ONE

Tanda to Panjwar

"She looked at the picture and admitted my fiancé was better looking than hers."

We met with Devinder in New York at her Richmond Hill, Queens, home on a snowy January morning. She offered us chaa and a plate full of biscuits. Next came the bowl of fresh fruit.

Undaunted by the visitors who had just arrived, her young granddaughter marched across the living room and sat in front of us to watch the cartoons that once marked the arrival of all our Saturday mornings.

Devinder wore a smile, one of those that have seen their share of what the world has to offer and now are content with a detached casualness for whatever may come.

It was clear that we were more anxious than her, so she paused with a smile and guided us to a February morning 36 years in the past.

We were in the North Indian state of Punjab, and it was the day she first saw Sukhdev. She had seen pictures before, but today was different. His wedding party arrived that morning to her parents’ farmhouse and were seated on a set of outdoor beds, assembled in the courtyard.

Devinder was getting ready when her friends rushed into her room and quickly scurried her to the stairs that surrounded that courtyard. They sat watching the men with the bright turbans from Amritsar and tried to communicate in the hushed voices that no teenage girls staring at their friend’s future husband can really keep down for too long. The girls were clandestine spies and chided each other to stay quiet so that the invading forces below wouldn’t make their positions. For Devinder, the aspirations of the life she was to live with the boy below passed through her eyes:

Life. Family. Festivals. Children. Old age.

In the years to follow, Sukhdev would occupy some of the roles she hoped for: husband, police officer, father - all appeared dutiful enough.

However, Devinder was too young to know that life outside the idyll of her parents’ farms was a powderkeg. Revolution was brimming in the countryside, and a struggle for human rights was about to explode. In the decade to follow, the Sikhs of the Punjab would require Sukhdev to play roles that neither he nor Devinder would have imagined on the morning of their wedding:

Soldier. Detainee. Escapee. Bank Robber. Resistance Fighter. General.

* * * * *

As Devinder’s granddaughter sits watching her cartoons, a picture hangs above the television. In fact, upon entering this house, it is the first thing you notice. It watches over the happenings of the house and seems a solitary guardian for these immigrants of Richmond Hill, Queens.

In the picture, Sukhdev lies dead in a field. The police who may or may not have been his killers are seen in the distance, and the villagers for whom he was General, mourn.

What isn’t shown within the frame is Devinder, by then a 31 year old woman, silently gaping over the lifeless body of her husband. Beyond the anxieties of a government trying to maintain its sovereignty and the struggles of those who contest its control, is the reality of a 31 year old woman looking at her husband’s body riddled by the state’s bullets.

Couples mark their time spent through birthdays, a new home, or a baby. Sukhdev and Devinder’s milestones were episodes of police torture, assassinations and jailhouse visits.

In many ways, this is simply a story of a revolution told by a girl once sitting on her parents’ stairs anxiously waiting to marry a boy who would grow to become the general of an insurgency.

Devinder Kaur was born in 1956 in a town called Tanda Urmar, in northern Punjab. Her father, Charan Singh Lahoria, had crossed the Pakistani border during the 1947 Partition of Punjab and South Asia. The middle of 5 siblings, Devinder, began school at the age of 5 and continued till the 10th grade.

When she was 13, a relative told her family about a boy who lived 60 miles away in the village of Panjwar. Charan Singh went to Panjwar, met the boy, and approved. With that, Devinder Kaur of Tanda Urmar and Sukhdev Singh of Pind Panjwar were engaged.

A year later, a photo of Devinder and some friends was taken at a dance performance and sent to Panjwar.

When we asked if she took an individual picture for Sukhdev, Devinder laughed and said, “No one took photos back then.”

Chuckling, she pressed on and described the arrival of Sukhdev’s photo from Panjwar as if she had just seen it for the first time.

“His photo came, and I showed it to my friends. All of them liked it. My sister was also engaged at the time. She looked at the picture and admitted my fiancé was better looking than hers and even tried getting me to switch. But why would I trade? Unlike hers, mine already had a job!”

These two photographs mediated Sukhdev and Devinder’s relationship until the day of their marriage.

On February 14, 1979, Sukhdev’s baraat (wedding party) arrived. The festivities took place in the fields next to the Lahoria house. Guests were seated on manjay, the outdoor beds that ubiquitously dot the Punjabi countryside.

This is when the girls of Tanda Urmar peeked through those stairways to steal glances at the arriving wedding party. The dazzling sight of a baarat from Amritsar wearing bright turbans impressed Devinder’s guests, and they remarked in admiration at how good her in-laws looked.

Next came the Anand Karaj, the Sikh marriage ceremony. Here, the couple united in their spiritual and physical journey before the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh Scripture and Eternal Guru.

After the Anand Karaj, the wedding party drank and danced in celebration. When the night was over, the Panjwar family took the bride to her new home.

Sukhdev was born in 1952 in his maternal village of Naushehra Pannuan in Tarn Taran. His father, Puran Singh, was a truck driver who had passed when Sukhdev was young. His mother was Kulwant Kaur, and his brother, Daljit Singh, was 4 years his elder. Of all the family and friends in Sukhdev’s life, he was closest to his cousin Paramjit. Devinder remembers them as inseparable brothers.

Currently, Paramjit is said to live in Pakistan and occupies every wanted listed published by Indian authorities.

Sukhdev studied in Panjwar until Grade 10 and then continued his schooling in a nearby town. Upon graduation, he joined the Punjab Police.

After their marriage, both Devinder’s family and Sukhdev’s grandfather pressured him to stop drinking. By 1980, he relented and planned to take Amrit, the initiation ceremony into the order of the Khalsa. Much of the Panjwar family began preparing for Amrit at a ceremony being organized by the Damdami Taksal, a Sikh seminary with a legacy from the early 18th century.

When the day arrived to take Amrit, to everyone’s surprise, Sukhdev did not show. The family waited and waited and after some dismay, proceeded to take Amrit without him. Sukhdev came home late that night. It was clear that he’d been drinking and confessed, “The time for amrit isn’t now.”

Sukhdev spent much of his work week in Amritsar. Devinder lived in Panjwar and typically, had to be cognizant of how she dressed and behaved. Sukhdev acknowledged this pressure and moved them both to Amritsar, where Devinder quickly began enjoying her new life.

A few months into the move, the couple welcomed their first son, Rajeshwar, on June 22, 1980. Devinder remembers the joy with which her family celebrated Rajeshwar’s arrival at the festival of Lohri. It was a happy time with a large gathering of Panjwar friends and family consuming ample liquor. However, there was a gradual change in Sukhdev. He started keeping late hours at work and remained elusive about his whereabouts. Devinder’s inquiries received curt responses.

“I’m at Darbar Sahib” he would say.

Darbar Sahib is a complex in Amritsar that houses Harmandar Sahib, commonly known as the Golden Temple and the Akal Takht, the seat of Sikh political power. In many ways Darbar Sahib is the center of the Sikh world. It welcomes a massive number of daily visitors, contains the world’s largest open kitchen (langar hall), houses Sikh treasuries and museums and is in the vicinity of the headquarters for many Sikh political and cultural institutions and groups.

Sukhdev’s changing demeanor concerned Devinder. He would sit in a room secluded for hours and meditate. With her son Rajeshwar pounding on the door, an openly worried Devinder lamented Sukhdev’s increasing distance.

A second son, Pardeep, was born on November 21, 1982. However, her husband’s temperament remained the same. It had hardly been three years into their marriage, and he was already spending as little time as he could with his family. When Devinder voiced her concern, Sukhdev would try to reassure her agony by repeating, “I’m going to Sant ji.”

Devinder had no idea who this Sant ji was or why he had such a strong impression on her husband.

Sukhdev was soon informed that his police posting was moved to Bathinda, a town 115 miles south of Amritsar. Sukhdev told Devinder he was going to reject the move. Rather, in a succession of sudden events, he took Amrit, transferred the family’s belongings back to Panjwar and left Devinder and the children at her parents’ house in Tanda Urmar. The family had no idea where Sukhdev went and day by day became increasingly worried. Weeks passed before Sukhdev finally came home one evening. He informed the family that the police were after him and it wasn't safe for anyone to be close to him. When pressed for details on why, he wouldn't specify, but told Devinder and her father not to worry.

And with that, Sukhdev left again.

Even today, Devinder remembers this as a drastic change in Sukhdev. He went from being a regular member of the Punjab Police, popular amongst his friends and villagers, to suddenly spending most of his time in the company of a Sant, who Devinder had no idea about. What Devinder didn’t know at that moment was that Sukhdev wasn’t alone. There was something pulling groups of people from Punjab to Darbar Sahib.

To rephrase Buffalo Springfield, there was indeed something happening here and what it was wasn't exactly clear. The sounds of that revolution brimming in the countryside were finally taking shape, and the battles lines were definitely being drawn. The characters of the play that would envelop the Punjab were beginning to make their entrances, and unknown to Devinder, her husband was already on stage.

To Be Continued …

[Courtesy: Lighthouse. Edited for sikhchic.com]

July 23, 2015

Conversation about this article

1: Kaala Singh (Punjab), July 23, 2015, 2:20 PM.

People like General Labh Singh had the courage to do what many of us did not. My heartfelt respect for this great man.

2: Taran Singh (London, United Kingdom), July 26, 2015, 10:00 AM.

Interesting and a good read. I wish the movies based on some of these heroes of our panth were a bit better as well.

3: Taran Singh (London, United Kingdom), July 27, 2015, 4:24 PM.

Where's this spirit gone now? I think it might still be there ... But there's no Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwala amongst us who can awaken this spirit in us?