Current Events

India is Literally Starving While Politicians Steal $ 14.5 Billion of Food

Part I

MEHUL SRIVASTAVA & ANDREW MACASKILL

Ram Kishen, 52, half-blind and half-starved, holds in his gnarled hands the reason for his hunger: a tattered card entitling him to subsidized rations that now serves as a symbol of India’s biggest food heist.

Kishen has had nothing from the village shop for 15 months. Yet 20 minutes’ drive from Satnapur, past bone-dry fields and tiny hamlets where children with distended bellies play, a government storage facility five football fields long bulges with wheat and rice. By law, those 57,000 tons of food are meant for Kishen and the 105 other households in Satnapur with ration books. They’re meant for some of the 350 million families living below India’s poverty line of 50 cents a day.

Instead, as much as $14.5 billion in food was looted by corrupt politicians and their criminal syndicates over the past decade in Kishen’s home state of Uttar Pradesh alone, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The theft blunted the country’s only weapon against widespread starvation -- a five-decade-old public distribution system that has failed to deliver record harvests to the plates of India’s hungriest.

“This is the most mean-spirited, ruthlessly executed corruption because it hits the poorest and most vulnerable in society,” said Naresh Saxena, who, as a commissioner to the nation’s Supreme Court, monitors hunger-based programs across the country. “What I find even more shocking is the lack of willingness in trying to stop it.”

UNPUNISHED

This scam, like many others involving politicians in India, remains unpunished.

A state police force beholden to corrupt lawmakers, an underfunded federal anti-graft agency and a sluggish court system have resulted in five overlapping investigations over seven years -- and zero convictions.

India has run the world’s largest public food distribution system for the poor since the failure of two successive monsoons led to the creation of the Food Corporation of India in 1965. The government last year spent a record $13 billion buying and storing commodities such as wheat and rice, and expects that figure to grow this year.

Yet 21 percent of all adults and almost half of India’s children under 5 years old are still malnourished. About 900 million Indians already eat less than government-recommended minimums. As local food prices climbed more than 70 percent over the past five years, dependence on subsidies has grown.

From the government warehouses, millions of tons are dispatched monthly to states including Uttar Pradesh, which are supposed to distribute them at subsidized prices to the poor. About 10 percent of India’s food rots or is lost before it can be distributed, while some 3 million tons of wheat in buffer stocks is more than two years old, according to the government.

FOOD GAP

Even after accounting for the wastage, only 41 percent of the food set aside for feeding the poor reached households nationwide in 2005, according to a World Bank study commissioned by the government and released last year.

In Uttar Pradesh, where the minister of food stands charged with attempted murder, kidnapping, armed robbery and electoral fraud, the diversion was more than 80 percent in 2005, the World Bank report said.

Fully 100 percent of the food meant for the poor in Kishen’s home district was stolen during a three-year period, according to India’s Central Bureau of Investigation, the country’s leading anti-corruption agency.

Hunger is worse in villages than in cities. Indians living in rural areas on average eat 2,020 calories a day, against a global average of 2,800 and 11 percent less than they did in 1973, according to government and United Nations’ data.

'BUZZ OFF'

When Kishen and other residents of Satnapur sought their monthly quotas at the village’s Fair Price Shop, as the ration stores are called, they’d either find a locked door or be told to return the following month, said Javeed Ahmad, the CBI officer leading the agency’s investigation of the scam for more than three years.

“Who is a person who holds a below poverty line ration card? A person of no influence,” he said. “If he shows up at the Fair Price Shop and there is no below poverty line wheat, you can just tell him to buzz off.”

The scam itself was simple. So much so, that by 2007 corrupt politicians and officials in at least 30 of Uttar Pradesh’s 71 districts had learned to copy it, according to an affidavit filed as part of a probe ordered by the high court in Allahabad, one of the biggest cities in India’s most-populous state and the home of the Nehru and Gandhi clan . All they had to do was pay the government the subsidized rates for the food. Then instead of selling it on to villagers at the lower prices, they sold to traders at market rates.

BIG DADDY

The first person to figure out how to run the theft on a mass scale was a man named Om Prakash Gupta, the CBI’s Ahmad said.

“Gupta was definitely the big daddy of the scam,” said Ahmad. “Over time, every district came up with more efficient executions of this system.”

Gupta was a six-time member of the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly and the owner of a family run grain-trading firm. By the time he ran for national parliament in 2009, he had been charged with 69 criminal offenses, including five murders, two armed robberies and gangsterism, according to a declaration he filed with the Election Commission of India.

In June 2011 the CBI also charged him with forging documents and other offenses in connection with food theft from the ration program. Gupta, who lost the parliamentary race, died of a heart attack in April at the age of 69 before a trial could begin on the food case. He wasn’t convicted of any other crime.

ONLY WARRANT

So far, he is the only senior political figure to have been arrested by the CBI over the food scam: Ahmad got a warrant after Gupta manhandled one of his investigators.

The CBI’s indictment of Gupta provides a glimpse of how the operation was run. Food purchased by the central government is trucked to districts like Sitapur, where Kishen’s home of Satnapur is located, and stored until marketing managers in the food distribution system sign off on its dispatch to the Fair Price Shops.

The owners of those shops, called kothedars in Hindi, bring cashier’s checks for the subsidized price of the supplies. A kilogram of rice, for instance, costs as little as 2 rupees, or about 3.6 cents, in most states. The market price for similar quality rice is about 10 times higher.

The shop owners are supposed to sell the food to villagers without making a profit.

Gupta got around the system in Sitapur by using a dummy firm called Naimish Oil Industries Ltd., according to the CBI’s indictment. It paid for subsidized rice, wheat and sugar from the warehouses, picking them up in Gupta-owned trucks, scooters and motorized rickshaws, then sold the food to private companies, according to the CBI.

MONEY TRANSFERS

Gupta and his family pocketed the difference by transferring the money from Naimish Oil’s accounts to their own, according to the indictment.

“While the government is getting real money, the foodgrains don’t actually go to the Fair Price Shops,” said Ahmad.

In one transaction investigated by the CBI, Gupta sold 17.7 million kilograms of wheat to four different companies hundreds of kilometers away in the cities of Kolkata and Raipur. The companies paid $2.1 million to Naimish Oil.

Over a three-year period, 110.6 million kilograms of wheat and rice meant for India’s poor was transferred from rail stations in Sitapur district to Bangladesh, according to the CBI’s indictment. In other transactions, the companies buying the grain were in Nepal, said Ahmad, the CBI investigator.

“Since they were paying tax, paying freight to the railways and actually delivering the promised foodgrains, nobody asked the question of where they procured them originally,” he said.

GROANING STOCKPILES

While the food theft by Gupta and his copycats around the state may have robbed people like Kishen of their dinner, it hasn’t put a dent in India’s stockpiles.

Deadly famines were a recurrent feature of life in India until the country embarked on the so-called “green revolution” in the 1960s, experimenting with high-yielding strains, irrigation and pesticides. The nation finally achieved self- sufficiency in food production in the late 1970s.

At the same time, the government began building up buffer stocks of food. While the Food Corporation of India is required to keep about 32 million metric tons of rice and wheat, bumper harvests have left the country with a stockpile of more than 80 million tons, according to the corporation. Stacked in 50- kilogram sacks, the food would reach from Sitapur to the moon, with at least 270,000 bags to spare.

To stop food rotting, the central government lifted a four- year ban on exports of wheat last year. In June, India donated 250,000 tons of wheat to Afghanistan.

STARKLY VISIBLE

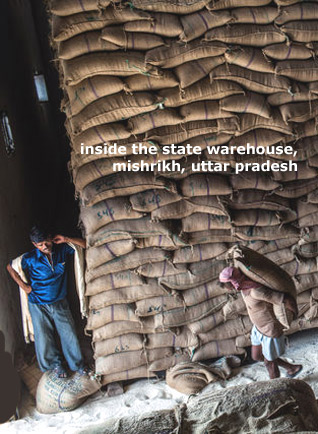

The nation’s food surplus is starkly visible at the state storage facility about 10 kilometers (6.3 miles) from Kishen’s village of Satnapur.

On June 28, 60 trucks loaded with bags of grain waited outside the walled-off piece of land, one of four similar stockpiling sites in the district. Inside, 40,000 tons of wheat and 17,000 tons of rice spilled out from a small warehouse and were stacked in the open in three-story-high piles, the blue tarpaulin covers tied tight with rope.

The trucks will be parked up for weeks before there is space inside so they can unload.

In Satnapur itself, the prominent ribs and bloated bellies of children playing in the streets give the telltale sign of chronic malnourishment. The village has no electricity, and the local ration shop has been closed for months, residents said.

Of the 106 village households that qualify for subsidized rice, wheat, sugar and kerosene used as cooking fuel, only about half are receiving it, said Surbala Vaish, 40, an activist with the local farmers and workers’ collective, known as Sangathin.

PEPSI OR RATIONS?

Urmila, a widow who guessed she was in her sixties and lives in a household of five, shows her ration card; it’s been 18 months since she last received her allotment.

A different government card recognizes her status as a widow, meaning she qualifies for rice and wheat for close to free. She’s had the card for six years and has never received her entitlement.

“If you can buy a Pepsi in every village in India, why can’t the government get us our rations?” asked Vaish, who lives in Satnapur. “The reason we don’t is because the government doesn’t want us to -- they all get a cut.”

The proprietor of the local ration shop is a frail, old man called Mattre. Like Urmila and many other Indians, he goes by one name. An illiterate cow-herder, he said he was granted the shop because he is blind. Instead of running it himself, he says he receives $3.50 a day from the village chief, who then takes care of the day-to-day operations.

'NOT MY FAULT"

“It’s in my name, but someone else runs the shop,” said Mattre, standing outside his straw-and-mud hut. “If the headman isn’t giving people their food, it’s his fault, not mine.”

The village head, actually a woman named Kumari Poonam Yadav, couldn’t be reached. A person who answered a cell phone number that villagers said was hers said he didn’t know anyone by that name.

In Sitapur town, an hour’s drive from the village, Anoop Gupta steps out of a white Toyota Fortuner SUV. He is Om Prakash Gupta’s son, and by the time his father died in April, he had won Om Prakash’s old seat in the state legislative assembly.

TOYOTA SUV

As Gupta, 42, walks away from the SUV, which retails for $37,500 according to Toyota Motor Corp.'s website, armed police officers push away the crowd of people rushing to touch his feet, a sign of respect. He walks across a courtyard to a small office behind a gas station, sits at a bare desk, shoos off his entourage and gives a spirited, one-hour defense of his father.

Gupta himself hasn’t been charged with any wrongdoing, although the CBI lists bank accounts in his name through which his family allegedly received money.

“Let me ask you this: If I had, or my father had, or my family had been stealing food from the poor in Sitapur, would they re-elect me?” he said. “I swear upon my dead father that this is a vendetta the CBI has against us. If I ever once stole a grain of rice from a poor man, it would be like eating the flesh of a cow.”

Cows are considered holy in Hinduism and eating beef is forbidden. While Gupta declined to discuss the details of the indictment, he said that his family might have mistakenly paid lower taxes on the transactions. His father and the family firm were simply procuring wheat and rice on the open market in Sitapur and selling to traders around the country, he said.

JUST A TRADER

“How am I supposed to tell if the wheat or the rice or the sugar in the local market is meant for a ration shop?” he asked. “I am a trader. I buy and sell thousands of tons of food a month.”

Over the past seven years, different court orders and changing state governments have resulted in at least three agencies being tasked with probing the theft: the CBI, a Special Investigative Team of the Uttar Pradesh police and the Economic Offenses Wing of the central government. In addition to the Special Investigative Team, both the state police’s Food Cell, and its Criminal Investigations Division are carrying out probes. Some of the investigations overlap; others run independently.

The CBI, for instance, is only looking at cases where food actually left the state, while the Special Investigative Team is looking at all the cases and the EOW is focused primarily on the money trail.

Continued tomorrow ...

[Courtesy: Bloomberg. Edited for sikhchic.com]

August 30, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Sunny Grewal (Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada), August 31, 2012, 12:06 PM.

It is this type of complete disregard for the poor and worship of the elite which has led to India being looted, embarrassed and massacred for a thousand years. The only duties which those in power have is to serve those below them, but the Indian class/caste system reverses this simple command of chain. If you look at western European countries there has been a tradition for the poor to rebel and wipe out elites which have abused them. Unfortunately the poor of India have had their spirit broken on the genetic level and it is passed on to the next generation. Of course, there are some exceptions in India. Well, just one, really, but the rest of India cannot be as lucky as being a Punjabi. But then, being a Punjabi today? Are they turning into Indians?