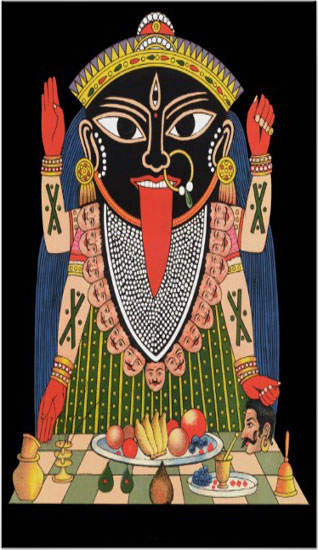

Above: Dina Nath Batra, whose lawsuit against Penguin India led the company to agree to destroy copies of Wendy Doniger’s book, in his office beneath portraits of right-wing Hindu extremists K.B. Hedgewar & M.S. Golwakar. Delhi, Feb 2014.

Current Events

India: Censorship by the BJP/RSS Batra Brigade:

Part One

WENDY DONIGER

THE EVENT

In February of this year (2014), after a long career of relative obscurity in the ivory tower, I suddenly became notorious.

In 2010, Penguin India had published a book of mine, The Hindus: An Alternative History, which won two awards in India: in 2012, the Ramnath Goenka Award, and in 2013, the Colonel James Tod Award.

But within months of its publication in India, a then-81-one-year-old retired headmaster named Dina Nath Batra, a proud member of the far-right Hindu organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), had brought the first of a series of civil and criminal actions against the book, arguing that it violated Article 295a of the Indian Penal Code, which forbids “deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class” of citizens.

After fighting the case for four years, Penguin India, which had recently merged with Bertelsmann, abandoned the lawsuit, agreeing to cease publishing the book. (It also agreed to pulp all remaining copies, but -- as it turned out -- not a single book was destroyed; all extant copies were quickly bought up from the bookstores.)

When Penguin told me it was all over, I thought it was all over, and was grateful for the long run we’d had.

There wasn’t anything special about my book; Batra had been attacking other books for some time. But what was special, and unexpected, was the volume and intensity and duration of the outcry in reaction to Penguin’s action: other authors withdrew their books from Penguin, defying it to pulp them, too; people accused the publishers of cowardice for giving up without even taking the case to court, in contrast with their former courage in successfully (and at very great expense) defending Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960.

One Bangalore law firm issued a legal notice suggesting that the Penguin logo be changed from a penguin to a chicken.

THE LAW

Some writers argued that Penguin could have won the case had it seen it through to the end. After all, these accusers said, how can you prove malicious intent in a book?

Alas, in some courts it could be very easy. To satisfy the terms of Indian law, statements in the book in question need merely be expected “to outrage religious feelings.” If you got the wrong judge -- and India is a place where the Supreme Court has recently reinstated a law criminalizing homosexuality -- you’d be convicted just for publishing a statement that you had good reason to believe might well offend someone.

It’s hard to imagine how you could write about any subject as sensitive as religion or history without outraging someone; such a rule would mean the end of creative and original scholarly thought.

Any new idea offends people who are committed to the old idea, which is to say, most people. Even in the hands of someone as intellectually challenged as Batra, Article 295a is a weapon of mass cultural destruction.

THE LAWSUIT

I still believe that the Indian law is the main villain in this case, but of course there is also another, secondary villain: Batra.

A closer look at some of his arguments in the original Penguin lawsuit reveals aspects of his mentality that obviate any possible hope that one might escape his denunciations by pulling one’s punches and avoiding “sensitive” aspects of Hinduism -- for instance, to take a case at random, sex, which Batra has objected to in my book (perhaps confusing it with Lady Chatterley’s Lover).

Obscenity is not the issue here. Nor is it a matter of truth or falsehood. For instance, the lawsuit insists: “The book also defames youth icon Swami Vivekananda when it states that on being asked what he will eat, Swami Vivekananda replied ‘give me beef.’”

The objection is not that this quotation is false, or insufficiently documented; it is true, and well documented. The objection is simply that repeating that statement in the book defamed Vivekananda.

Batra has other objections to the book’s citation of certain Hindu texts. He complains:

That in this book all books written in Sanskrit by all and sundry are treated as sacred scriptures at par with the Vedas. That the book does not inform the readers that Vedas are the supreme scriptures which supersede anything and everything which is in conflict with the Vedas.

And then, at greater length:

That in this at Page No. 106 the author has correctly stated that text of Vedas did not undergo any change of correction during thousands of years. When the text remains the same, it is oblivious [sic] that its meaning and message have remained the same. Therefore the core principle of Hinduism has remained the same as enunciated in Vedas. In other words, the core principles of Hinduism are eternal (Sanatan). Distortions and deviations do not constitute the core of any religion. That in the aforesaid book, the author has made basic blunder of equating and mixing core principles of Hinduism with the stray distortions.

This pious view simplistically declares most of Hinduism heretical and therefore irrelevant. The “stray distortions” may very well be irrelevant to some forms of Hindu worship, but they are highly relevant to any serious understanding of Hindu history.

Much of my work, including the book under attack, has been devoted to the representation of aspects of Hinduism that the Victorian Protestant British, when they ruled India, scorned as filthy paganism: polytheism, erotic sculptures, spirited mockery of the gods, and rich, earthy mythology.

In the wake of the British, in their shadow, many Hindus who worked with the British -- I am tempted to call them sepoys -- came to share these sentiments. They also took on the British preference for the Sanskrit texts created and perpetuated by a small, upper-caste male elite, regarding as beneath contempt the vast oral and vernacular literatures enriched and animated by the voices of women and lower castes.

It is this “alternative” Hinduism that is denied by Batra and by many Hindus in the fundamentalist movement known as “Hindutva.” Pankaj Mishra, in his review in The New York Times Book Review, expressed the hope that my book would “serve as a salutary antidote to the fanatics who perceive -- correctly -- the fluid existential identities and commodious metaphysic of practiced Indian religions as a threat to their project of a culturally homogenous and militant nation-state.”

In 1999, the Bharatiya Janata Party / Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (BJP-RSS) government put Batra in charge of a project to “Saffronize” all the history textbooks in Indian schools (i.e., to make them confirm with Hindutva ideology). They deleted passages dealing with the caste system and beef-eating in India, and added arguments that ancient India had both airplanes and the nuclear bomb.

Now Batra is trying to do it again.

Another passage in my book “outraged” Batra’s “religious feelings” for a different reason. I wrote, “Placing the Ramayana in its historical contexts demonstrates that it is a work of fiction, created by human authors, who lived at various times …”

And this was his complaint:

That in this book at Page No. 662 the author has hurt the religious feelings of millions of Hindus by declaring that Ramayan is a fiction. This act of the author breaches various sections of IPC [Indian Penal Code].

To eliminate all the books that share this understanding of the text as fiction, we would have to ban just about all of the extant scholarship on the Ramayana. And indeed, it is no accident that Batra was among those who attacked A.K. Ramanujan’s famous essay “Three Hundred Ramayanas” in 2009.

Nothing could bring into clearer focus the threat to freedom of speech in contemporary India than the fact that a serious political attempt was made to remove this classic essay from the BA syllabus of the History Department at the University of Delhi and from the in-print list of Oxford University Press India; and, until now, nothing gave more hope for the survival of democracy in India than the qualified success of the protest against that attempt.

THE ARGUMENT: RELIGION & THE ACADEMY

This argument has nothing to do with religious civility; it is about the clash between pious and academic ways of talking about religion and about who gets to speak for or interpret religious traditions.

The misunderstanding arises in part from the fact that there is, in India, no real equivalent of the academic discipline of religious studies. With only a few recent exceptions, students in India can study religion as a Hindu or Muslim or Catholic in private theological schools of one sort or another, but not as an academic subject in a university.

And so the shared assumptions underlying this discipline are largely unknown in India.

Batra and I are talking past one another, playing two different games with the textual evidence. But he thinks there is only one game, and is determined to keep me off my own field.

To debate a book you disagree with is what scholarship is about.

To ban or burn a book you regard as blasphemous is what fascist bigotry is about.

The American Academy of Religion recently issued a statement of support for me, which said, in part:

But to pursue excellence scholars must be free to ask any question, to offer any interpretation, and to raise any issue. If governments block the free exchange of ideas or restrict what can be said about religion, all of us are impoverished. It is only free inquiry that allows a robust understanding of the critical role that religions play in our common life. For these reasons the AAR Board of Directors fully supports Professor Doniger’s right to pursue her scholarship freely and without political interference.

In response to this, a member of the Hindu American Foundation posted a comment on a blog in which he stated, in part:

Four words in the AAR statement -- to offer any interpretation -- leap out at me. To a lay person who deeply respects my religious tradition, it is this unconditional and self-proclaimed right “to offer any interpretation” which lies at the root of what is wrong with religious studies today.

The notion that one might “ask any question” but not offer interpretations, that there are questions -- and, indeed, facts -- without interpretations, reveals a nineteenth-century concept of history that is no longer viable. It betrays a basic misunderstanding of the nature of academic inquiry, the same misunderstanding that is at the heart of Batra’s misreading of my books.

Continued tomorrow ...

[Courtesy: The New York Review of Books. Edited for sikhchic.com]

April 22, 2014