Columnists

Science Versus Religion:

Where's the Beef?

by I.J. SINGH

For a conflict that has no legs in my opinion, the perceived animosity between Science and Religion has unnecessarily occupied the best minds over many centuries.

I know that even today many discerning minds are busy ferreting out even the smallest conflict between what science tells us and what theology and traditional religion ask us to believe.

An obvious temptation is to parse religious writing and hold it to scientific test.

Are the words and the models of reality they posit logical and reasonable? Are they verifiable? Are the logic and the theories internally consistent? Is it possible to reconcile the different models postulated by the various prophets of different religions?

Admittedly, there are many scientific theories and constructs that are impossible to observe or measure given the present state of out technology, but we can infer their existence and their truth by their properties and by experiments that can be replicated.

Many religious believers doubt, if not reject, the scientific bases of life. This reflects the attitude that scientific conceptions are no more than hypotheses to be proven, discarded or amplified with additional evidence, while absolute truths are found only in religious revelations.

Do religions speak with one voice on God, heaven, hell and many other postulates that define the religious reality? Do we even have a uniformly accepted, logically consistent definition of these terms, such as God, that are the fundamentals of organized religion?

And if we don't, how can we possibly navigate our way through a debate with conflicting and exclusive premises?

Among the variety of existing religions, since religious truths also appear to be at loggerheads with each other hence they, too, should be labelled as only tentatively held. (This is not to argue that there is not also a set of largely shared and universal values and practices that underlie the major religions of mankind.)

What many scholars do - and will continue to do - is to reinterpret the metaphoric language of their own favourite religion along lines that offer the least visible conflict with our current understanding of science, and thus offer a justification - a validation - of one's own brand of religious belief.

What cannot be easily reconciled is then conveniently rationalized as magic and mystery that underlie all religious truths.

When we cite selective or incomplete citations from our favourite scripture to buttress our own specific and limited view of reality, this to me is merely proof of the adage that our choices in life are usually visceral and then we bring to bear what sense and intellect God has given us to justify the choices that we have already made.

I do not intend to load this presentation with citations and references, not because few are available, but because I mean to frame the issue so as not to bury it under the weight of a plethora of scriptural or scholarly opinions.

I am gratified that there is minimal if any inconsistency between the steady march of science and the very clear logical worldview of Sikh teaching. But exploring that is not my purpose today. I leave that to others who have made such a case most persuasively.

For a carefully detailed construction of the rational vision of Sikh scriptural writing and its consistency with the march of science, I refer readers to H.S. Virk and Rawel Singh, along with many others.

Many good scholars will go a step further and label Sikhism a "scientific" religion. I wonder how suitable such an appellation is. Science demands that its theories be internally consistent, verifiable and replicable. And scientific theories are never dogmatically held, only tentatively embraced; they are modified, even jettisoned, if newer experimental data so warrant. Ideally, they are testable. Some matters like evolution, though, are not replicable; but they remain demonstrable.

Religious truths need to be internally consistent, logical, and not at conflict with reality as it continues to be unfolded to us by time and technology. But they are not testable, nor are they meant to be incomplete - to be modified or abandoned as nature unfolds its reality before us.

Then where starts the genesis of this so called conflict between science and religion?

It's true that life was much more mysterious eons ago when it started. Little of even the simplest things were understood, so much remained mysterious. And God to many of us then was where he remains even today - where all mystery originated, resided and ended.

The so called "conflict" between science and religion continues to arouse passions even today in the 21st century, even though by this time we would expect considerable enlightenment.

The experience of Galileo in 16th century Rome and the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial in America are potent reminders of how convoluted and slow progress is.

The Pew Foundation has compiled a compelling evidence of popular contemporary American cultural attitudes to science, religion and the perceived conflict between the two. In the popular mind, the conflict still continues to survive and thrive.

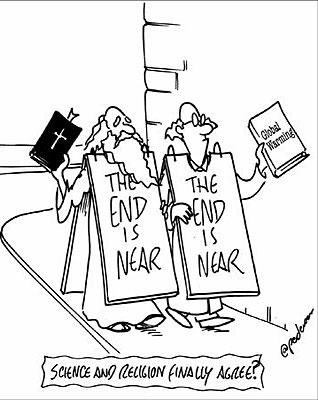

Clearly science and religion derive their worldview from very different perspectives and methodologies. The result: a natural and inevitable conflict in earlier times. At least theoretically, historians and scientists now reject such a conflict and define an interconnection between the two.

Ian Barbour too has enunciated his thesis on the nexus between science and religion most persuasively.

What then to believe? Science that changes by the day or religion that speaks of universal and eternal truths. The gulf appears to be wide, and the debate endless and eternal.

Not so long ago, the New York Times highlighted a public school teacher in Florida. He was now required to teach the findings of evolutionary theory. Why? Because little over a year ago, in February 2008, the Florida Department of Education adopted a requirement that evolution be taught, because it is, as the department declarted, "the organizing principle of life science."

His dilemma: how to present the ideas of evolution without undermining the religious faith of his own and his students.

What he is trying to do is not just to address a lack in information that a few hours of lectures and labs might fill but to bridge an ideological divide.

Establishing meaningful communication across such an abyss is never easy, whether it exists in politics, religions or matters of the heart.

I believe that our present troubles begin with too literal - I would label it too unimaginative - a rendering of the Old Testament and its chapter on Genesis, along with the role of an unfathomable God in our existence.

Our understanding of the nature of God lies at the root of our problem. Keep in mind that humanity worldwide has created an anthropomorphic God, very much in the human image, with a fixed address somewhere out there in outer space.

I think to reason thus is to create a trap for ourselves.

We need to look for God in our inner space, not in outer space.

Science and religion are not inimical to each other; they are complementary. If they complement each other (I.e., complete each other), then it follows that, like two sides of a coin, they deal with different set of realities, different questions and very different objectives.

Science seeks to discern, discover and categorize order in nature or what we call creation. So scientific laws, in fact, deal with statements of probability. A particular hypothesis is likely to be true (not rejected!) based on the available evidence. The door is never shut on new evidence. Many things that we know today were unknown yesterday.

For example, such a basic fact as the number of chromosomes was a matter of some dispute half a century ago, when details of cell structure were unknown, as was the role of DNA.

However, and it is critical that we understand this simple truth, how we put to use the discoveries of science and technology is a question that is independent of the discovery itself.

There is no morality inherent in technology. The morality comes from how we define the ethics to justify its usage. To search for morality in technology is to place a burden it cannot handle and a misuse of technology. It is not the purpose and the objective of science.

Religion, on the other hand, is misused when we try to explain or justify scientific theories and hypotheses based on religious constructs. Religion speaks to our sense of self and how it is constructed. From this flows a body of knowledge that we call ethics. These are not hypothetical constructs to be tentatively held but are eternal values and truths; thus societies and nations are constructed.

To unearth scientific factoids from the Bible (Genesis) orThe Guru Granth, or any other scripture is a disservice to it and a misuse of religion.

To take Sikh teaching as an example, I personally find it an absolutely mindless exercise when we explore as literal truths when Guru Granth speaks of 8.4 million species. It would not bother me one bit, nor would it diminish Guru Nanak an iota, if someday science tells us that the exact number is more or less than that. Similarly, the Founder-Gurus would not be enhanced one whit if the number turns out to be exactly true.

It seems to me that the writings of gurbani use the language of allegory and metaphors and have to be interpreted in the context of time and culture. In the vernacular of the time (norma loquendi), this expression merely speaks of a large, almost incomprehensible number - much as we might say "a gazillion" in the colloquial idiom of today.

I apply similar interpretations of language, context and culture to explore concepts of satjug, duapar, tretaa and kaljug that come to us from ancient Indian philosophic traditions and are heavily incorporated into all Indic religions.

Hinduism, for instance, uses these terms very much literally in creating a construct of time and its steady march forward from creation.

Sikhism, on the other hand, uses these terms as powerful metaphors for the state of our mind (Guru Granth: "Kaljug rath aggan ka koorh aggay rathvaho" [GGS: 470]; "Satjugg sub santokh sareera" [GGS: 445].

The ideas of Creation, Creationism and Evolution, for instance, saddle us with similar issues of interpretation. Sometimes scholars interpret the lines from Guru Granth ("Keeta pasaao eko kuvaau// tis tay hoay lakh dariaao") to mean that the universe was created with a single command of God and from it evolved millions of streams. This, they contend, stands in stark contradiction of Darwin and his model of evolution.

When taken in context, these lines speak to me of the richness and creativity of nature, not of a God micromanaging his creation and our existence.

Our problem in the interpretation of such divine poetry arises when we take a further step into the unknown and 'invent' or adopt the simplistic idea of God that may have been Judeo-Christian at its onset, but certainly now dominates the practice of most believers of most religions. This is the idea of an anthropomorphic Creator, micromanaging creation, somewhat akin to a potter or a sculptor in his workshop, spending his day fashioning ashtrays and cups. Such a God is not what Sikhism talks about.

On the divide between science and religion, Stephen Jay Gould and Frances Collins, eminent scientists both, take the middle ground. We have seen the electrifying debates between two very fine scientists, Richard Dawkins, a atheistic biologist, and Francis Collins, the genome pioneer who believes in God, that have dominated the conversation in this area over the last decade. The main thrust of evolution is its mechanism - Natural Selection - and that remains a matter of continuing scientific exploration.

Ultimately, our problem lies in mixing of religion and science. The two remain complementary but different from each other.

Science speaks of the rules of nature - of Chemistry, Biology, Physics and Mathematics. The technology of science tells me how to build a house or a nuclear bomb, but it does not tell me why I should build either or what use I should put it to.

For these and other questions like why I am here, who am I, and how to fashion a life, I need to probe religious values and ethics. Mapping the human genome is a scientific achievement, what use we put that information to requires ethical exploration and parsing. Using such knowledge to attack disease would be ethical; to construct human clones would not be.

Scientific findings are free of ethical implications. How we arrive at such findings and what use we put them to can and do have ethical implications. The distinction is critical to how and when both religion and science serve us.

Science and religion remain two sides of the same true coin of reality. How can one side have any value without the other; how can one diminish the other?

Science can explain atomic energy and even free it for us. How we use or misuse it lies outside the domain of science but in that of religion and ethics.

Science tells us what is, religion tells us how to rejoice in it, what to make of it and how or how not to use it.

These are matters that are at the intersection of science and religion.

August 23, 2009

Conversation about this article

1: Harinder (Bangalore, India), August 24, 2009, 11:31 AM.

Religion is about promises of an after-life and science is about promises in this life.

2: Maouj Kaur (New York, U.S.A.), August 24, 2009, 6:24 PM.

Is religion about the after-life: bani kehay suno rae santo maran mukt kin payee.

3: H.S. Vachoa (U.S.A.), August 24, 2009, 9:14 PM.

I.J.Singh has tried to put religion and science at an equal altar. However, the historical reality states that most religions are nothing but political philosophies for expansionism. Hinduism is based on racial enslavement of humans, whereas Islam and Christianity have historically endorsed slavery. Entertaining religions as ethical philosophies is a fallacy.

4: Ravinder Singh Taneja (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 25, 2009, 8:18 AM.

Framing the right questions is the underpinning of good philosophy - and science. Is our desire to reconcile Science and Religion necessary? Are these (Science and Religion) separate domains that can co-exist within us? We are creatures capable of logic and reason but also capable of mystical flight and awe. Is that all in the brain? How can we be so certain that we know anything at all? What about Consciousness? Is that material, or does it have a material/biological basis? If religion is mistaken about the nature of Reality - as many scientists like Dawkins assert - how can science be so sure that it is right? As Dr. I.J. Singh points out, all scientific knowledge is tentative. Any God that can be comprehended by man-made scientific frameworks and tools is not worthy of worship, in my opinion. I would go further and say that God is unknown and a mystery and religions teach us how to live and relish that mystery; science does not. I speak not of organized religion (which is a cesspool) but of the religious experience that our Gurus speak of. The success of Science since the Copernican revolution has coloured our view of what Science does and what it does not. It has become the new altar of worship and scientists the new priesthood. There is a similar discussion current on another forum where some good Sikh scientists insist that Gurbani must be viewed through the lens of logic and science alone. Does that mean non-scientists cannot understand Gurbani? Science has undermined religion but has not displaced it, which leads me to believe that we as a species need both. The desire to harmonize the two may be an error.

5: Raja B. Singh (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), August 25, 2009, 11:42 AM.

I am guilty of skipping through this article rather hurriedly, for it is too long. Sikh Gurus were naturalists and keen observers of what happens around us in this universe. This is truly reflected through their writings as enshrined in the Guru Granth. Religion is to help a person lead a better life and be a useful part of the society. In order to achieve this, he/she has to be in harmony with his/her surroundings, spiritually and physically. Gurbani does that as it understands the universe/cosmos and our position in this universe. Hence, in two words, the twain shall meet and does so in the Guru Granth. It helps us be one with the creator by understanding his creation (call it scientific or whatever). As enshrined in the Japji Sahib, all of creation, all laws (of nature) are under His 'hukam'. Gurbani's interpretation is subjective and Dr. I.J. Singh's subjective opinion is no different.

6: Roopinder Singh Bains (Surrey, British Columbia, Canada), August 25, 2009, 6:22 PM.

'8.4 million lifetimes' was a Hindu concept prevalent at the time of Guru Nanak. Guru Nanak used the expression exactly as he used the words 'Ram Rahim Puran Quran': these were terms that the general populace understood, as figures of speech. It did not reflect an endorsement of these concepts, personally or within Sikhi.

7: Gurjender Singh (Maryland, U.S.A.), August 26, 2009, 5:20 PM.

Rules of any religion can be misinterpreted to justify any wrong-doing in daily life. On the other hand, scientific rules or laws cannot justify any wrong action or application. God controls science. In Asa di Vaar, Guru Nanak clearly says: "Air is flowing with your (God) Hukam, and rivers too with your Hukam ..."

8: D.J.Singh (U.S.A.), August 26, 2009, 7:15 PM.

Religion relies on revelation. Man is taught to live in the love and fear of God. Science depends on observable, repeatable experiences. To date, none of these have led to God. The educated believe religion without science is superstition. The poor regard science without religion as only materialism. Gurbani teaches us: "Truth is the highest virtue, but higher still is Truthful Living." (GGS:62). Therein lies our salvation!

9: H.S. Vachoa (U.S.A.), August 27, 2009, 9:41 PM.

Gurjender Singh, The argument is an idealization because it fails to understand the reality that mmost religions are systems of political and social opression. Neglecting reality and getting into idealism only leads us to murky understandings. The conclusion of the article - that religion is the source of morals falsely legitimizes moral pervesity in religions by futher implying that non-religious people are immoral.

10: I.J. Singh (New York, U.S.A.), August 28, 2009, 8:41 AM.

I appreciate the many comments on my essay. H.S. Vachoa, in perhaps a hasty reading of the essay, makes several leaps of imagination and interpretation that do not sit well. Surely plenty of evil has been done by organized religion, but religions have also done a lot of good. If "neglecting reality and getting into ideals can lead to murky understanding", neglecting ideals too can do untold harm to society. When we read "all men are created equal..." that is an ideal, not always the reality. To not see the reality makes progress impossible; to not see the ideals makes progress unnecessary. H.S. Vachoa seems to have missed the objectives of the exercise in this column. It was to dileneate what ideally are the objectives of "Science" and "Religion." My theme is that they are different but complement (complete) each other in our understanding of reality. Neither science nor religion have always been honest but exploration of that was not the purpose here. Perhaps another time we can catalogue the sins of each. How my take "falsely legitimizes moral perversity", as Vachoa alleges, really escapes me.

11: Harbans Lal (Arlington, U.S.A.), August 28, 2009, 2:01 PM.

At the outset, the title of Inderjit's column 'Science Versus Religion' may be worrisome if one took it to mean that there is a conflict between the two disciplines. However Inderjit went on to explain that in Sikhi, there is no such conflict. In fact, science is an asset in Sikhism. Let me explain. Soon after Partition, I joined Punjab University for the degree program in Pharmaceutical Sciences (1949-52). The school was located in the Glancy Medical College at Amritsar. There, we started holding informal and formal study circles where Sikh students and teaching staff of the medical college could gather to talk about issues in Sikhism. I recall one gathering where the late Dr. Harbhajan Singh of Surgery Department suddenly asked me a question: "Which section of civil society would be more amenable to appreciate Gurmat?" he asked. I recall responding: scientists, of course! I remember this discussion because the next day I saw it reported in the Punjab press. It was unusual for the Punjab press to report the goings-on in a study circle but it must be due to the attractive topic. Of course, the attendees of the Study Circle asked me for an explanation, which took much of the evening and was considered worthy of reporting by the press. As Inderjit wrote, religious truths need to be internally consistent, logical, and not at conflict with reality as it continues to be unfolded to us by time and technology. That is true of Gurmat and that is what would make present day scientists more comfortable with Sikhism in contrast to some other religions. Scientists are trained to a mindset of inquiry about truth and they are rewarded in the process of their pursuits. The condition is that they must be true scientists and they are not there just as professionals who are there to inflate their ego. This is not a trivial point. In reality, ego in the scientists is often an obstacle, which leads to a closed-minded attitude from their belief that the scientists know it all. On the converse, our religious clergy and religious scholars are not free of the same obstacle either. Their egotism over "we know it all and science is only a blind man's crutch" is equally hindering. As the late Sir John Templeton used to say: egotism is not so much a personal flaw but rather a habit of mind which inhibits the learning process necessary for appreciating others' views or disciplines. Most scientists learn to avoid the stagnation that comes from accepting a fixed perspective. The Sikh scientists that I know are systemologically open-minded, always seeking to discover new insights and new perspectives. To a Sikh scientist, the expanse and the wonders of the creation brings humility, as well as a challenge for creativity all in the partnership with the Creator, as is often stated in the hymns of Guru Granth. I once asked my friend, Dr. Narinder Singh Kapany, a scientist of worldwide recognition, to tell me which hymn from Guru Granth Sahib he remembered humming in recent few days. He right away came up with the following Shabad: pankhee ho-ay kai jay bhavaa sai asmaanee jaa-o // nadree kisai na aav-oo naa kichh pee-aa na khaa-o // bhee tayree keemat naa pavai ha-o kayvad aakhaa naa-o - "If I was a bird, soaring and flying through hundreds of heavens / and if I was invisible, neither eating nor drinking anything / even then, I could not estimate Your Value. How can I even describe the Greatness of Your Name?" [GGS:12] All of us have favorite hymns to hum and we can make a comparison; it will reveal our state of mind based upon our life attitudes. Science can both inspire and assist religion to explore a rich future of boundless possibilities. Education in science at the same time when we are learning the Guru Granth can also make us realize that the Sikh religion is much more than the preservation of ancient traditions that are so often repeated by many clergy. To be an enviable Sikh society, what is true of the scientists has to be true of the religious scholars and Sikh clergy as well. Guru Granth teaches us all to be humble in front of the indescribable expanses of nature and the laws of creation. In humility, the clergy must accept challenges to old assumptions and let the religious rites and meditation not remain stuck on ritualistic traditions. Instead, they must unveil the Creator through the connectivity with Creation that our religious practices may offer. To me that is what a meditation on Waheguru (Infinite Wisdom) means and that is what the Gurmat Symbol of Ik Oankaar (One Reality expressed through the vast creations) means. Being a scientist by profession and a Sikh by faith, I can appreciate the relationship very well. As Inderjit explained, Sikhi supports a positive relationship between science and religion. Severance of this relationship will be damaging to civil society. The key in accepting a positive relationship between science and religion is to cultivate a spirit of humility in front of the Infinite Wisdom simply by being open to the opportunity of our worldly existence considered to be within the divine reality. The life of a scientist as well as a faith practitioner or of a clergy then may become an occasion of progressively unfolding at the same time scientific as well as spiritual discoveries to the fulfillment of human life. Thank you, Inderjit ji, for bringing science and religion in perspective.

12: H.S. Vachoa (U.S.A.), August 28, 2009, 5:13 PM.

I do agree with I.J. Singh that religion and science are entirely different but I disagree with him on why both are different and they are certainly not close enough, not even by a stretch to be called "complementary". Can we neglect the enshrined human enslavement (both moral and physical) especially under Islam, Christianity and Hinduism? In India, there are 300 million untouchables living in perpetual enslavement of Hinduism. Nowhere have we found the mention of these painstaking realities in IJ Singh's view of religion, rather all of them have been brushed aside and abjectly neglected - to idealize "religion" as a vessel of ethics and morals. My argument is not against idealization itself but idealization of religion. Idealizing ourselves when we say "All men are created equal" is different from idealizing a religon. These are the idealized values of Libery and Equality, and NOT religion, and are a result of a break from the dark chapter of religion. Religon never gave us the values of Equality, Liberty and Human rights in history, at least most. How is it therefore justified to consider religion a source of morality? In this view, I.J. Singh gives us a self-serving idealization of religions when he says that religion and science are complementary to each other. He writes: "Science and religion are not inimical to each other; they are complementary. If they complement each other (i.e., complete each other), then it follows that, like two sides of a coin, they deal with different set of realities, different questions and very different objectives." Not only does this argument again fail to look at the reality of history but it relies on an empty assumption that morality is the virtue of religion. So, by this logic non-religious people can never be moral. The attempt of the author, though well-intentioned, is incomprehensive.

13: I.J. Singh (New York, U.S.A.), August 29, 2009, 9:26 AM.

As I requested in my previous note, it might be prudent to defer cataloging the sins or failures of both religion and science to another time so as not to muddy the waters by raising too many issues at the same time. To focus on the failures of religions or science was not the intent of my essay here; hence none of the bloody history of any religion was touched. Not that religions haven't been bloody or science hasn't been dishonest or been held hostage to religious passions. Both science and religion have, at times, elected to bend their truths to serve political masters. There is no assumption here that non-religious people cannot be moral; history tells us otherwise. By what stretch of imagination can one deduce that from my essay I do not understand. There is also absolutely no assumption in my logic that religious people are unfailingly virtuous; again, history and commonsense tell us that. I don't see where I have idealized the "practice" of any religion - whether self-serving or not. There is also no assumption here that all science is always correct or even objective. This is what half a century in science teaches me. Scientific endeavours, however, in the long run are self-corrective. That is the nature of scientific methodology. The way people view the world and others around them is often framed by their sense of self and ethics - for most people, including the founding fathers of this nation, this sense stems largely from their religious framework, if they are of a religious bent at all. That's why my objective was to explore the different objectives (and methodology) science and religions serve in exploring our reality. It is a defined and narrow focus - keep that in mind.

14: Ravinder Singh Taneja (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 29, 2009, 12:10 PM.

It seems to me that some of us may have missed the conclusion of the article. It does not appear to be - as a reader has suggested - that religion is the source of morality; I don't think that was even the theme. Whether Religion is the source of all morality is quite another discussion; regardless, one cannot divorce the two. Dr. I.J. Singh's point seems to be that we cannot drive a hard line between science & religion or claim that they are in mortal conflict. Their methods may differ, but their goal is the same: apprehending Reality or Truth - and in this sense, they are indeed complementary.