Sarbat Khalsa and The Swiss Landsgemeinde, Part I

by Dr JOGISHWAR SINGH

Being a Swiss citizen and having witnessed its workings from up close, I am very impressed by the system of direct democracy in Switzerland. It is a remarkable system which has enabled Switzerland to ensure reasonably harmonious co-existence between completely diverse German, French, Italian languages and cultures within a united, federal system.

I grew up in India where an effectively unitary system is well disguised as a federal system with a Union List, a State List and a Concurrent List anchored in the Constitution. Reality, as any serious analysis will show, is that the Centre in India has effective control, even having the power to dismiss validly elected governments in the states under article 356 of the Indian Constitution.

I had occasion to work with a senior member of the Swiss parliament in 1988. During this period, I had the opportunity to closely interact with Swiss parliament members. I also discovered the nuances of the system of direct democracy in Switzerland where any law passed by the federal or provincial parliaments can be called into question through a popular referendum provided the minimum requisite numbers of signatures is achieved on a petition challenging the law being called into question.

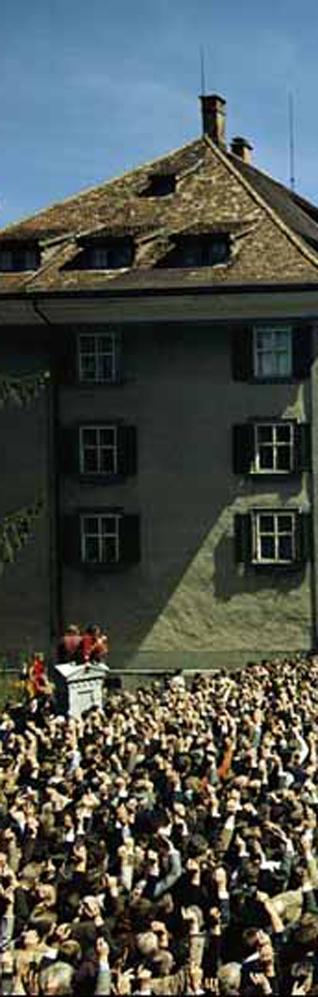

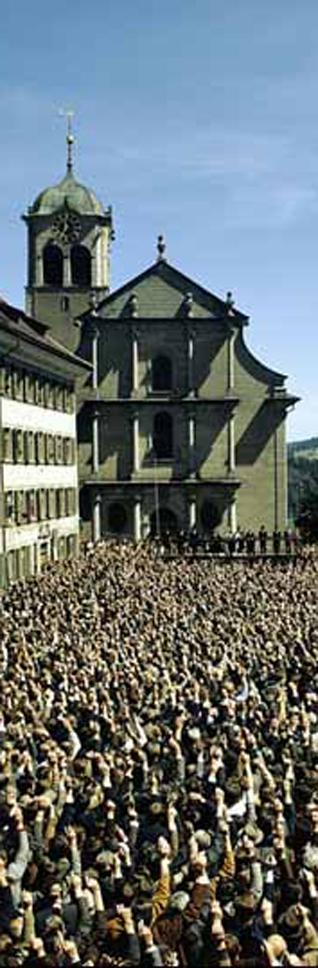

During my study of Swiss democracy in action, I came across the institution of the Landsgemeinde, which can be roughly translated as 'Village Assembly' (graam sabha, in the Indian context).

Delving into the Landsgemeinde, I realised how much the traditional Sikh system of the “Sarbat Khalsa” resembled its

workings. This made me think about several other similarities that I had noticed between the Swiss and the Sikhs.

Even a superficial study of Swiss and Sikh history shows that both the Swiss and the Sikhs have been excellent soldiers who fought valiantly against oppressive rulers. Both were prized as mercenaries, recruited by others in their armies. A striking example of this is the performance of the Sikh soldiers fighting for the British colonial masters at the Battle of Saragarhi in the 19th century and the Swiss soldiers fighting for the French Bourbon King Louis XVI during the storming of the Tuileries Palace in Paris in the 18th century.

In both cases, the Swiss as well as the Sikhs fought to the last man in defence of the foreign master who had hired their services. The Swiss were and are excellent agriculturists, as are the Sikhs. They have a long tradition of resisting tyranny and oppression. Both have traditionally been hard working, efficient and conscientious in accomplishing tasks assigned to them.

However, the destinies of the Swiss and the Sikhs evolved totally differently on the political front.

The Swiss achieved independence in several steps between 1192 and 1815. They have built a state with a unique system of direct democracy. They have never lapsed into rule by kings or aristocrats, once they had thrown off the yoke imposed by the Habsburg empire, the Prussians, the French or any other foreigners who tried to dominate them.

The Sikhs lost their political sovereignty to the British in 1849 and never regained it.

REMOTE ORIGINS

It is interesting to briefly study the evolution of the Landsgemeinde system in Switzerland.

In the rural cantons (Canton = province) of central Switzerland, the Landsgemeinde evolved from the “Plaid” (Landtag), an assembly during which the Count’s representative - the Bailiff - pronounced justice not only in the presence of witnesses but also of other persons represeting the populace (alili quam plures). As the jurisdictional competence flowed to the Cantons, the Bailiff gave way to an Amman or Landamman who used to pronounce judgements before an assembly, the future Landsgemeinde, which also used to elect local authorities, passed laws and decide administrative matters. Meetings used to take place where the traditional “Plaids” used to be held.

Such assemblies were already taking place in central Switzerland in the 13th century. The term “Landtag” remained in use in the Schwytz canton till the 15th century; in Nidwald till the 19th century. The original hypothesis that the Landsgemeinde originated from marching associations (“Marchgenossenschaften”) is not believed any more, even if it shows links to popular associations, particularly in mountain valleys like those of Uri and Leventina. Similarly, there is no support for formerly held beliefs that the Landsgemeinde was in a direct line of succession to germanic judicial institutions (“Ding”), which continued since the time of germanic invasions.

MIDDLE AGES & MODERN TIMES

The Landsgemeinde, as we presently understand it, was developed first in the provinces of what is nowadays described as “Primitive Switzerland”: in cantons Uri in 1231, in Schwytz in 1294, in Unterwald in 1309 respectively. It got extended to Zug in 1376, to Glaris in 1387 where separate sessions for different religious beliefs began from 1623. It began sporadically since 1378 and regularly since 1403 in Appenzell where a division took place in 1597, just like it did for the Canton on the basis of religious belief (Catholic, Protestant).

Several areas under the rule of cities or rural areas organised Landsgemeinde assemblies, sometimes under the direct influence of their protector cantons. Such examples are Urseren, Leventina, Bellinzona and Blenio valleys, as well as Einsiedeln, Küssnacht, Werdenberg, Uznach, Oberhasli, Upper Simmental, Entlebuch, Sargans and Lavizzara valley.

The Landsgemeinde resembled popular assemblies such as those held in the jurisdictions of the three Rhetic Leagues, in several areas of Valais canton and in the valleys of Engelberg as well as Toggenburg, both belonging to an Abbey. There are

formal similarities between the Landsgemeinde and the Assemblies of Commoners, assemblies frequently organised for the administration of peasant communities and users’ guilds.

The tradition of war assemblies, known even amongst the soldiers of City Cantons and for federal campaigns, continued in certain cases till modern times.

In rural Cantons the Landsgemeinde became the highest forum (“Höchste Gewalt”). In the absence of separation of powers, it enjoyed universal competence. It used to elect magistrates, the higher judiciary, delegates to Parliament (“Diète”) and the principal officers. It used to establish customs, promulgate new laws and had to approve the laws passed by the Diète before such laws could be made applicable. It used to handle administrative matters like external relations, recruitment of soldiers as mercenaries, taxes, finances, attribution of civic rights, internal borders.

It also had a judicial role, even though it began delegating civil matters to specialised tribunals during the later Middle Ages and criminal matters to Courts of modern times, except in Nidwald where it served as a criminal court under the denomination “Landtag” till 1850. The limits of its field of action were not defined. In theory, it could take back any competence that it had delegated to another authority.

PATICIPATION QUALIFICATIONS

Any man apt for military service, enjoying civic rights, whether inherited at birth or subsequently acquired, could participate in the Landsgemeinde from the age of 14 years (sometimes 16 years). Every such participant had the right to propose individual initiatives except in Uri where any motion had to be presented by at least seven persons from seven different families to be considered acceptable.

The annual ordinary assembly used to take place at the end of April or beginning of May. In cases of special need, extraordinary or additional assemblies were also held (“Nachgemeinde”). The meetings were organised in accordance with a ritual full of symbolic significance. The Landamman used to preside over such assemblies, a position of great honour and prestige.

The Landsgemeinde played a key role, especially during the wars of Appenzell (1401-1429), the Peasant War of 1653; at the beginning of 1798 till the proclamation of the Helvetic Republic and in the decade 1830-40. However, the liberty enshrined by this institution was not like the concept of liberty based on natural rights, propounded by the Enlightenment philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was considered more as a privilege reserved to the local “people of the area”.

Such liberty was the consequence of imperial decrees, acquisition through purchase of feudal rights which had slowly permitted the dilution of feudal privileges and the conversion of tenant rights into proprietary rights in a process around the Lake of Four Cantons till about the year 1400.

The existence of the Landsgemeinde did not prevent the development of a ruling class in the rural Cantons, in Grisons or in Valais. However, it did hinder the emergence of a monopoly of state power by a ruling patrician class on a hereditary basis.

The ruling classes were never able to eliminate the need to get their actions approved by their constituents through the Landsgemeinde. It did lead to electoral corruption which, however, was sought to be countered by forcing the holders of

posts of profit to paying in a substantial part of their profits to the public treasury or tailoring the laws governing such positions to reflect the spirit of equality between elected beneficiaries of financial favours or even between the candidates.

LANDSGEMEINDE IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES

The Landsgemeinde system is considered by many to be an ideal form of democracy.

It made progress in 1798 when Napoleon’s intervention led to the fall of the existing Swiss Confederation. But it was not cherished by the Helvetic Republic, established under Napoleon’s thumb. The Act of Mediation restored the Landsgemeinde system and all the rural cantons re-established it, albeit with modified features in conformity with the legislative acts that had established the basis for Switzerland (Act of Mediation of 1803, The Federal Pact of 1815 and the federal Constitutions of 1848 and 1874).

During the period of revolutions in Europe in 1830, several references were made to the tradition of the Landsgemeinde as a democratic system enjoying great popularity and acceptance in the rural areas. Thanks to this tradition, the rights devolving

from direct democracy were enshrined in cantonal constitutions framed in the 1830s. The Landsgemeinde served as a historical model at the federal level for the extension of democratic practices during the second half of the 19th century.

While the Constitution of 1848 was based on the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers and the doctrine of popular sovereignty of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, marking the start of a liberal, representative democracy, the revised Constitution of 1874 relied more on the tradition of the Landsgemeinde in the sense of a democracy of assemblies.

The powers exercised by the Landsgemeinde vary depending which canton they are situated in. They are the broadest in Uri in terms of elections, legislation, finances. They are similar in Appenzell Inner-Rhoden which maintained the right of free intervention of all participants, replaced in Appenzell Ausser-Rhoden since 1876 by the rights of “Volksdiskussion” (citizens’ propositions have to be presented in advance in writing).

The system of secret ballot replaced the vote by open show of hands for the election of Senators in Appenzell Ausser-Rhoden in 1876. This right was again returned to the Landsgemeinde between 1995 and 1998. Secret ballot systems for election of Senators and cantonal ministers were introduced in Glaris in 1971 and in Nidwald in 1994. Show of hands was replaced by secret ballot for votes on constitutional amendments or legislative bills in Obwald in 1922.

The suppression of the Landsgemeinde was accepted after several attempts in Zug and Schwytz in 1848, in Uri in 1928 respectively. Such abolition took place after secret ballots in Nidwald in 1996, Appenzell Ausser-Rhoden in 1997 and Obwald in 1998 respectively, after having been refused in popular votes in 1919, 1922, 1966 and 1973 respectively.

Nevertheless, institutions modelled on the ancient cantonal Landsgemeinde continue to exist in big bourgeois municipalities like the “Oberallmeind” of Schwytz and the “Korporation” of Uri since their separation from the state in 1833 and 1888 respectively.

The abolition of the Landsgemeinde in Zug, Schwytz and Uri was chiefly the result of regional tensions, added to rivalries of political parties and the fact that the system disadvantaged remote regions. Such abolition lately in Nidwald, Obwald and Appenzell Ausser-Rhoden has taken place mainly for organisational reasons like lack of adequate space for such meetings following the right of vote granted to women voters, coupled with a growing preference for modern forms of democracy like the system of secret ballots.

CONTINUED TOMORROW - Part II: Sarbat Khalsa: Landsgemeinde of the Sikhs?

[Dr. Jogishwar Singh was with the IAS (Indian Administrative Service) before leaving India in 1984, the year of cataclysmic events for Sikhs in India. With an M.Sc. (Hons School) in Physics and an M.A. in History from Panjab University, Chandigarh, he did his D.E.S.S. at Sorbonne in Paris, followed by a Ph.D. from Ruprecht-Karls University in Heidelberg, Germany. Now a Swiss citizen based in Le-Mont-sur-Laussanne, he is serving as a Managing Director with the world famous Rothschild Group in Geneva, having earlier served as Senior Vice-President, ING Bank, Switzerland and Director with the Deutsche Bank Switzerland. He is fluent in eight languages and has basic knowledge of two others.]

December 19, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: K.J. Singh (New Delhi, India), December 20, 2011, 1:20 PM.

Very impressive comparison of what Sarbat Khalsa connotes, compared with Swiss tradition/ style of democracy.

2: Davinder Deol (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), December 22, 2011, 4:07 PM.

Wow, i didn't think we had so many similarities with the Swiss. Congratulations for finding common groud. Congratulations for attaining such a senior post with the Rotschild Group, they are a very old and respected organisation.

3: Manmohan Singh Virk (Arlington, Virginia, USA), May 26, 2013, 5:28 PM.

Dear Dr Jogishwar Singh ji: Your comparison of the Sarbat Khalsa with the Swiss Landsgemeinde is illuminating and instructive. Regrettably, the Sarbat Khalsa was subverted by Maharaja Ranjit Singh for his vested and selfish interests. He ruled for himself with the support of the Sikhs mainly. He was a great leader, in many ways like Napoleon. The Sarbat Khalsa was revived in the 20th century again to serve the political interests of Akali leaders but not of any consequence for the Sikhs. I have read some of your other writings and am so very impressed. I wish we had more persons of your intellectual reach, scholarship and grasp of Sikh history and tradition. I say that with a great sense of pride. I wonder if there is a way for me to talk to you or write to you.