Books

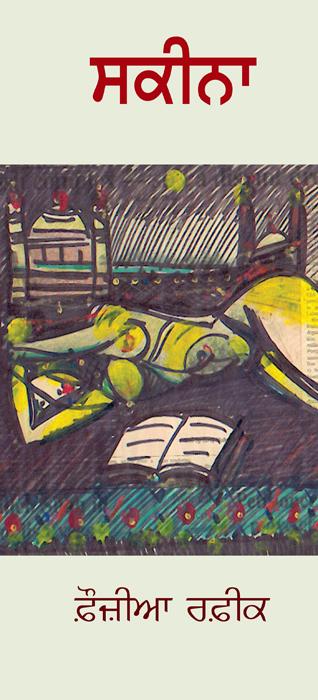

Skeena

A Book Review by RUPINDERPAL "Roop" SINGH DHILLON

Every so often an important novel is written, enriching the canon of Punjabi literature.

Skeena, a novel by Fauzia Rafique, is one of those.

She began writing it in 1991, completing it in 2004, when it was initially released in Pakistan, but then available only in Shahmukhi script. It was released in nine cities there, and was a resounding success.

This is of course very positive for Punjabi, a language neglected on it’s home ground, especially in Pakistan, and positive for Fauzia Rafique, for her novel does not pull any punches, nor does Skeena shy away from often taboo themes in Islamic society, and indeed all Punjabi communities. To place it in a genre, one could call it Feminist Literature. That in itself is amazing, as it has gained kudos in Pakistan, considering the environment there since Zia, and definitely since 9/11.

The book was released last month in Canada, both in the Gurmukhi transcript (the version I have read) and translated in English. I think indeed it should be translated into French and Spanish as well.

Skeena is a journey of a smart girl who questions everything. We meet her at the age of seven, and the story then takes us to young adulthood, into the Pakistan of General Zia, to Canada, and a forced marriage with a complete stranger, to finally finding love with the last person she expected under the sun amongst the blueberry fields of British Columbia.

This is no Hollywood saccharine-filled story, or a Bollywood fake-fantasy, or despite what I have said, stereotypical, east-is-worst-and-west-is-best plot. Skeena is the stark and true experience typical of many a Punjabi woman, in this case one bought up in Islamic Culture, but it can so easily apply to those women bought up in Sikh or Hindu culture as well.

What is the common factor? Punjabi attitudes.

Reading Skeena bought up many issues for me, general themes and points significant to the state of Punjabi Literature today. It needs to be examined in the context of these issues.

Techniques in how to write prose have moved on a lot in the last century or so. The other factor that has moved on is the subject matter and how honestly it is dealt with. What may have seemed great in Russian and English literature (other than Urdu and Hindi, the greatest influencers on Punjabi language in the last 100 years) in Victorian times, and pre-partition India is now stale, boring and irrelevant. There has been a malaise in Punjabi literature, confounded, I think by the following factors.

- Male domination in writing

- Religious domination, but often the incorrect interpretation of the faith

- Sycophantic behaviour of the established writers

- Greedy Printer-Publishers

- Political strangulation of the artist

- The public itself not reading

- Writers' life experience only restricted to the village

- Conservative values

All of the above are shattered in Skeena, if not by the protagonist, certainly by Rafique’s writing.

It is a well know fact that society is judged culturally by two yardsticks: its religious beliefs and its art. Punjabi society puts little value on the latter, though it then bemoans why its language and rituals are being lost by the young, especially those in the diaspora.

Russian, English and Spanish societies, taking but three examples, put great emphasise on language and literature. The English worship Shakespeare, to the extent one thinks no one anywhere in the world or in any other language can write like him. Obviously a false premise, but one that shows how important literature is to reflect a society's wants, truths and desires (as Skeena does).

The Russians treat their writers like demi-gods. What is more interesting is that in all of these societies, the greatest readers are the women. Not the men. So clearly, to ensure that one’s literature is relevant and well read, one cannot ignore women. Yet, Punjabi has done so, never giving women writers (Amrita Preetam is the one true exception) a voice. Worse, the men do not have a clue what it is the women want to read or what experiences they need to read to fulfil their spiritual needs. This failure means that Punjabi writers can never be read that widely, and how can any man really capture what has happened to a woman that well? Feminist literature is a necessity in Punjabi, a voice as important as the Dalit’s.

There are positive points in faith. Islam brings unity, encourages belief in one God. Hinduism brings order and Sikhism has placed all men of all faiths equal and, more importantly, women at the same level. The failure has come in interpreting and applying these faiths, or ignoring the real messages, or using them to suppress weaker members of society.

In Sikhism, it is clear - man and woman, apart from the obvious physical differences, are equal in rights. Yet in practice, Punjabi culture dominates, placing women as subservient.

This is even worse, when viewed through caste, as in Hinduism,

and if ones takes Skeena’s word for it, much worse in her Muslim society. Conservative values such as this often clash with the democratic soul of art. Punjabi literature will

not truly shine again until such conservative views are challenged, without the fear of a fatwa. In fact, all that the latter achieves is “apnay pairaan vich kuhari marni”.

The proof of this is seen in the way Salmon Rushdie’s Satanic Verses was treated, and Behzti, the play in Birmingham was tackled. We have all forgotten what made Punjabi literature great. Guru Nanak was a rebel and all of his poems and writings in the Guru Granth are a direct assault on the established attitudes of organised religion. The same is true of Sufi literature. Yet if one was to do that now, the extremists will come down like bricks on you, a fact so well highlighted when all that Skeena wanted to do in Zia’s Pakistan is visit a few Sufi melas.

I found Rafique’s writing here brave and fresh. I have been constantly told what Punjabi people will take or not take, and not to write certain things. I was told off for using the word naked, to describe a woman. I was told by one publisher that I could not show love between two women (it was not pornographic, yet despite him saying Punjabi readers were not ready, I put it on a blog, and have had so far 3,000 hits), or that I could not depict incest, because it was wrong.

Subjects that I know cover reality, and subjects that I know English Literature has dealt with for decades. So I sanitized much of my writing.

Guess what! Rafique has not. Skeena at one point depicts two lesbian couples, one of them Pakistani. Skeena does not shy away from masturbation, has swearing, and deals with reality. Has it made it a bad novel, has it made it into some porn? No, it has helped match it with the best of European and Oriental Literature. This is grown-up stuff, and much needed. The new generation of Punjabi reader is much more savvy and is bored with reading about village life and Z-TV-style bickering over land, between jathani and durrani, etc., etc. That is why no one reads Punjabi anymore.

So considering that most Punjabi literature nowadays is written by Sikhs in Gurmukhi, to find a blunt and in-your-face novel coming from a Pakistani woman, is not only refreshing but makes one wonder how many gems across the border are there?

Navel gazing by the established writers is strangling voices like Rafique’s. We need to ignore these dinosaurs who will be dead soon, and read and write more novels like Skeena, to kick start Punjabi again. I think my last few points are obvious, and I don’t directly need to go into them further, but rather they will become apparent as we cast our eye back on Skeena style-wise and plot-wise.

The style of Skeena is completely different from anything else I have read in Punjabi to date. It is much easier to follow, despite its local accent - I have to admit, there were a number of words used that were unknown to me, which I assume are unique to the area Skeena comes from. For example vahna, instead of vekhna, and aouna instead of puchhna. But the construction of the sentences is such, one can follow what is happening or deduce it, even when one is unfamiliar with words. It was actually clearer and easier to read than most Indian produced Punjabi, as it was not littered with Urdu and Hindi words (unless the character spoke in these languages). This made it very friendly for the diaspora Punjabi student, compared to many other books.

The structure of the sentence, although pure Punjabi, felt familiar, and I could not tell at times whether I was reading a book in English or Punjabi, due to the way it was written. Metaphors and similes were used in the same way that English applies them.

Again, this makes the book a good choice for a Punjabi student from the West. The breaking up of the novel in four parts was inspirational. Quite often it felt like I was watching a film, rather than reading a book. All this helped. In Media Res, repetition and back story were often used as well. Again this worked very well. The language was of a classy high level, despite the foul words emitting from some characters. In conclusion, the writing style placed this book at an international level.

You never felt the writer was semi-literate and only exposed to the locale of the village, as is often the case with many Punjabi writers. She understands the world of the village, where Skeena’s bha ji was head honcho, she understands the city, in this case Zia’s Lahore. She understands Canada (although poor Skeena does not).

The plot follows a girl who is not afraid to question the irrational goings-on around her. I don’t want to give too many plot details away. But in summary, we have a seven year old girl who questions the treatment of servants, even when they are polite.

Skeena is taught to say please, but scolded when she applies this to the household help. Skeena does not shy away from questioning the illogical nature of Wahabbi Islam as imposed in Pakistani society from Bhutto’s time right up to now. Especially on the treatment of women. What is more confusing for her is when Gamu, a servant only a few years older than her (Skeena is depicted as seven) beats his wife up, her mother has him flogged, but in other cases it is suggested he has the right to do so, as the woman (as I understood from this novel) is there to obey the man.

She witnesses the same servant drunk with her brother, questioning the local Mullah on this point of faith. Dissatisfied, they force alcohol down the man’s throat. But empathy does not last too long for this man, as he falsely accuses a young woman walking at night on an older Skeena’s behest, with a young man, of having sexual relations and gets the whole village to stone them.

Skeena wants to be a lawyer but is told that a good Muslim woman does not enter man’s domain - strangely by the very mother that protected Gamu’s wife. She is forced to ignore any academic ambition as an adult, compared to when she was a child. Gamu left an indelible mark on her, but ran away since he killed, while drunk, a woman he mistook for his wife. This is very relevant later in the story. Annoyed, Skeena goes with a friend, Rafu, to a Pakistani People’s Party meeting. This event is to prove fateful. Not only is she then forced to remain in the village, having brought shame upon the family by being arrested, but is made to marry a man she does not know, over the phone in Canada.

Skeena keeps a scrapbook, which highlights all her feelings and the people she looks up to, including leftist types, and those that some societies may interpret as Muslim terrorists. She takes this book abroad with her, to feed her memories of life in Pakistan.

It is in Canada that life becomes worse rather than better. She escapes Zia’s Pakistan, to find herself married to a doctor who does not love her, has her (unknown to her) as one of many wives, and despite his middleclass appearance, reminds one of the Maori husband in Once Were Warriors, on a good day. Worse, she is kept housebound for a whole decade. Life becomes even more unbearable, as she is barren and has the worst mother-in-law one can imagine. Do her family in Pakistan help? No, as behzti and izzat are higher values than her daily life.

And so is set the scene for how an educated Punjabi Muslim girl must face the world, surrounded by morons until one violent night circumstances lead her to be able to break the yoke,

and find herself in the arms of a Sikh lover who, unlike all the other men in her life, treats women with respect, and kindness. One would think she has found a beautiful conclusion but the plot thickens, and her life is made unbearable again, after two planes are flown into the twin towers by Arabs one fateful autumn day.

Her new society can not distinguish between her background and that of the Arabs. All Muslims are stained with the same brush in the great democracies of North America. Even her Sikh lover, Iqbal, cannot escape the image Osama bin Laden has conjured up in the collective Canadian mind. All brown folk look alike, don’t you know. This is where the diary she keeps, with clippings of genuine freedom fighters in it, proves fateful. After all, in freedom-of-speech America, what is an educated person doing, expanding their mind with reading Karl Marx, or empathizing with the Palestinians?

Why is a Muslim woman involved with a Sikh? Surely a middle age Pakistani woman must be at the centre of Al Qaeda?

Having spent the first part of her life fighting the unfair aspects of Islam and Punjabi culture, she is now forced to justify the same, and being from that culture becomes the crime.

This is the background, in a sketch, of the novel. I would heartily recommend reading it if you want to flesh all this out and to see if she copes with it, and how.

The flaws are minimum. Plot-wise, the Gamu story threw me off a little and I was confused with how, when sleeping with a non-Muslim, she did not notice the obvious physical difference that should be there. I spoke to Fauzia about this, and she told me: “This was to show her naivety, a characteristic reared in young women through their upbringing where sexual aspects of life are never discussed, keeping them as ‘sitting ducks’, ignorance being synonymous with innocence”.

So she was a naïve woman, who had only known Ihtsham’s body, and knew not anything else. What am I talking

about? Well, I am going to keep this vague, because it is something I hope intelligent students who perhaps one day may study this book in high school will spot. Maybe not, as in the six years of it’s publication, Fauzia tells me I am the only one who has spotted this obvious point.

Perhaps it is the obvious testimony to Skeena’s naivety. This is a tragic character, the modern Puro, an educated Punjabi Pakistani Muslim woman, who was never given a choice in the direction of her life. The sad thing is it was not always the men, but the woman, one so close to her, who failed to assist her ... or how can I say this? jaan-kay iss

haal vich ous nu paahya. It brings to mind what Debi Maksoospuri once sang, “aurat aurat naal vair karma kio nahi chaddi?”

This is a must read with a very realistic plot and honest perspectives on Islam and those against it, on women and how Punjabis treat them, and how as a country Pakistan went from Jinnah’s vision to the mire it is today; how the west went from being friends to anti-Islamic. But this is just the canvas.

The detail is much more interesting. The amity between Punjabi Muslims and Sikhs in a strange land. The help from women, even from different cultural backgrounds. The fall from grace of a man, and then how he turns his ways around. The desire for a man you love, whose name you do not even know, and not having the choice to choose your path. The failure of Punjabi culture, even today, towards women.

In 1699 Guru Gobind Singh created the Khalsa, which was all about democracy and equality. One that definitely extended to women, way before the suffragette movement strived for women's equality in the West in the 20th century! Yet our people have failed to apply this is practice, especially for our women. But, as this is a Pakistani novel as well as a Punjabi one, let’s move away from the Sikh perspective.

The ideals of Sufiism are also there … yet we fail to apply that love, the basis for Punjabi literature as well.

Skeena’s mother failed her, when she did not allow her to go to see the Sufis dancing and singing at their festival a couple of blocks away. Look at how what Skeena then did changed her life forever. The Sufis were described by Maa ji as un-Islamic.

Really?

In the same way, we are failing a thousand Skeenas today. A thousand Sukhinders. A thousand Seemas. How can you come to any other conclusion, after reading this gem? It must feature on all university reading lists for Punjabi.

June 9, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), June 10, 2011, 9:03 PM.

"Aj kee Picasso" ... pardon the pun! 'Sakina' has opened the floodgate of delicious memories of the potpourri of the musical dialects spoken in present-day Pakistan, the land of my birth. Luckily we have an encyclopedia of languages in Guru Granth Sahib. As a child I had subliminally absorbed various dialects. "Vahna" and "aouna" were common expressions. With the tragedy of partition, painful as it was, dislocation brought about the seeding operation, and transplanted the various Punjabi dialects to mix with Majha and Malwa dialects. For example, a housewife from Jhang Meghana now settled in Delhi where Hindi/Urdu was then spoken, was heard scolding the boy who was the help: "Mundu (boy), thum kabi kabi kam acha karta ho, par kabi kabi thumara habay mar wandaay hun" - "Boy, sometimes your work all right, but on other occasions you appear as if in mourning for your dead family." Language being alive imbibes the influence of foreign languages and produces a delightful newer dialect of Punjabi. In 1954, when I arrived in Singapore, the old Sikh driver wanted a rubber hose to wash the car. He asked me if I would buy him a "gethay da hoje". I said, "But why not a rubber hose?" Painfully, he explained that "getha" in Malay language 'woj rubber!" On another occasion, I went to a gurdwara where the presiding Bhai ji announced the next Sunday's programme and said: "Minggu daay minggu ethay diwan sajdha hai ji" - "There is a weekly diwan." "Aj kee Picasso" - of course, meant "What shall you cook today?" Have more stories to share for another occasion. In the meantime, trying to get hold of "Sakeena". I mean the book.

2: Kuldip (Crawley, United Kingdom), June 13, 2011, 4:12 PM.

Judging by Roop's own Punjabi writing, this must be amazing, so I am going to order it. Thanks for reviewing a book written in our mother tongue.

3: Dhillon (India), December 26, 2011, 7:40 AM.

Very interesting post ... Thanks for sharing :)